“If the orally disclosed confidential information is important, then the disclosing party probably should confirm it in writing to protect itself from the hell of trying to prove a solely oral disclosure.”

Nondisclosure Agreements (NDAs) sometimes specify that the confidentiality obligations cover disclosures in any form, whether that be oral or written. On one level this make some sense. Why should it matter how I disclose it to you? If its confidential, you need to keep it secret.

However, practically, enforcing or defending an alleged breach of an NDA in connection with a solely oral disclosure can be difficult and expensive. Therefore, solely oral disclosures may be completely excluded from NDA coverage. However, it is more common to allow coverage of oral disclosures, but only if they are confirmed in writing to the receiving party within a certain amount of time after the oral disclosure. For example an NDA may provide:

“For an oral disclosure to be within the scope of the NDA, it must be designated confidential at the time of disclosure and followed by a written memorandum to the receiving party within twenty days of the oral disclosure clearly providing notice of what specific information was confidential.”

Why should coverage for oral disclosures be limited in this way?

Receiving Party’s Concerns

The receiving party should want the disclosing party to clearly explain what is confidential in writing. Memories are feeble. Can you remember exactly what was said in a meeting one year ago? Will everyone agree with your memory of what happened, particularly if there are financial incentives for the other party to remember something else?

The cost of defending disputes involving oral disclosures is likely to be high. Each person who was there when the oral disclosure occurred will likely have to be deposed and questioned about what happened. Such factual disputes will not be resolved quickly. Instead of all that, why not just create a written document which explains what was disclosed?

You might ask: Can’t we just rely on someone’s meeting notes? If they are not circulated to the other side close after the time of disclosure, the other side may question when they were created and whether they are accurate.

The requirement that the oral disclosures be documented and sent to the other side quickly, is likely to prompt early identification and, possibly, resolution of disagreements regarding what was disclosed. It allows the receiving party the opportunity to object that the written memorialization of the oral disclosure is inaccurate. Therefore, the receiving party should review such confirmatory memos closely to ensure they accurately reflect what was disclosed orally.

Allowing an NDA to cover solely oral disclosures increases the chance of disputes regarding what was disclosed. It also is likely to drive up the cost of defending a claim of NDA breach.

Disclosing Party’s Concerns

Doesn’t the disclosing party want to avoid providing limitations on what oral disclosures will be covered by an NDA? In theory, yes. But practically proving breach of an NDA based on an oral disclosure will probably be expensive and difficult.

If there were only two people in the room when the disclosure occurred, you and the other party. It will be your word against his or her. The classic he said vs. she said. And unless you are able to show some defect in the other party’s credibility related to the NDA, you will likely loose because you have the burden to show a breach.

If there were multiple people in the room and you get a lot of agreement from them on what happened, then you might have a better chance. However, you are still going to spend a lot of money in deposing and gathering evidence from each of them to prove your case.

Therefore, if the orally disclosed confidential information is important, then the disclosing party probably should confirm it in writing to protect itself from the hell of trying to prove a solely oral disclosure.

Couldn’t we keep solely oral disclosures covered by the NDA as a fall back and just plan to never rely on it? Yes, this might work if the other side will agree (i.e. they didn’t read this post) and you are only going to be the disclosing party and not the receiving party–that is, if the NDA is not a Mutual NDA.

Conclusion

Limiting solely oral disclosures from coverage by an NDA is generally beneficial to the receiving party. This is riskier for the disclosing party, but documenting confidential disclosures in writing is likely to help the disclosing party avoid disputes about what was disclosed and protect its confidential information.

In a 2016Â

In a 2016Â

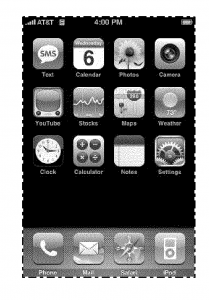

When considering whether two trademarks are similar for conflict purposes, the marks are considered in their entireties, including their appearance, sound, and commercial impression. Sometimes one of those attributes stands out to distinguish the marks even when similarities exist in the other attributes.

When considering whether two trademarks are similar for conflict purposes, the marks are considered in their entireties, including their appearance, sound, and commercial impression. Sometimes one of those attributes stands out to distinguish the marks even when similarities exist in the other attributes.