When discovering a solution to a problem, it is not uncommon to think, “Why didn’t I think of this earlier?” The question arises with inventions in general: “Why didn’t someone invent this earlier?”

Jason Crawford attempts to answer that question for bicycles in an post titled, “Why did we wait so long for the bicycle?” He considers a number of possibilities, such as technology factors, design iteration, the quality of roads, competition from horses, and economic factors.

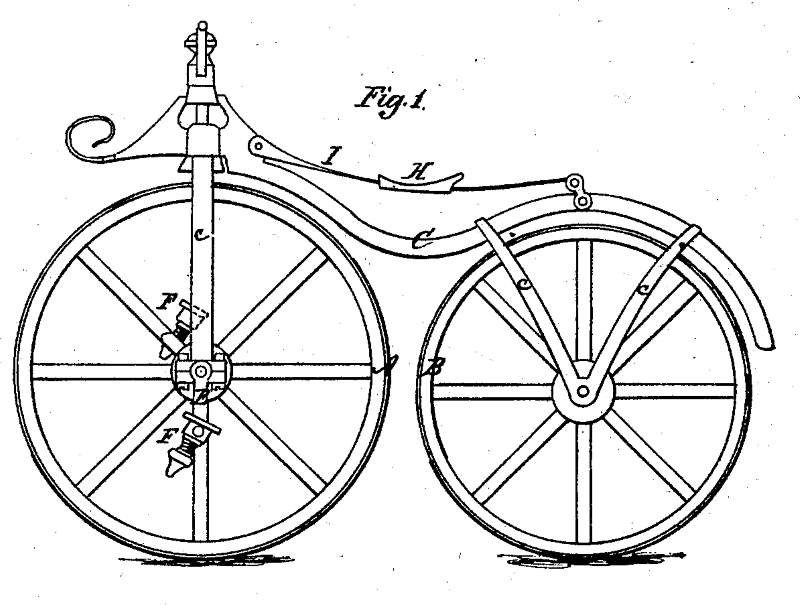

Crawford dates early references to human powered four wheel vehicles to the 1400s. He says it wasn’t until 1817 that that a two wheel ancestor to the modern bicycle was invented by Karl von Drais, which he called Laufmaschine, or “running machine. ” It had a wood frame, no peddles, and was powered by pushing off the grounds with one’s feet. Drais was an aristocrat with free time to tinker.

But the key advance over the Laufmaschine was the addition of peddles, which didn’t arrive for decades (maybe between 1839 and 1860).

And chains and gearing reportedly didn’t arrive until still later in the 1880s.

Crawford, considers whether the technology had not yet advanced sufficiently to allow the modern bicycle to become an adjacent possible. In other words, maybe “advanced metalworking was needed to make small, lightweight chains and gears of high and consistent quality, at an acceptable price–and that no other design, such as a belt or lever, would have worked instead.” Further, maybe inflatable (pneumatic) tires, which arrived around 1888, were important.

However, Crawford discounts the technology cause, at least somewhat, after considering other inventions, such as the cotton gin, and the flying shuttle, that took a long time to arrive and their prior invention didn’t appear to be limited by the state of technology.

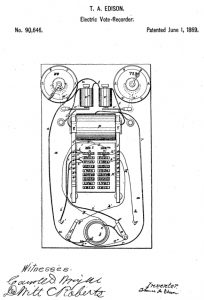

Crawford concludes the need for economic surplus was one of the main contributors to the delay in the arrival of the bicycle. Nassim Talab has also noted this when he said, “Knowledge formation, even when theoretical, takes time, some boredom, and the freedom that comes from having another occupation.” Talab notes that many inventions originated from the English clergy, whom had extra time on their hands.

Crawford says, “it seems that there needs to be a certain level of surplus to support the culture-wide research and development effort that creates inventions.” He also notes that “Maybe GDP per capita just has to hit a certain point before people even have time, attention and energy to think about new inventions that aren’t literally putting food on the table, a roof over your head, or a shirt on your back.”

This fits with Nicola Tesla’s explanation of the importance of having time to both develop ideas and let them incubate, when he said, “After experiencing a desire to invent a particular thing, I may go on for months or years with the idea in the back of my head.”

Inventing is probably facilitated by (1) sufficient technology advancement to support the invention and adoption of the invention (i.e. the invention and its adoption is within the adjacent possible) and (2) sufficient economic surplus so that persons have time for thinking and tinkering.

“After experiencing a desire to invent a particular thing, I may go on for

“After experiencing a desire to invent a particular thing, I may go on for