The US Government proposed, and the Apple v. Samsung trial court adopted, a four factor test to determine the “article of manufacture” for calculating total profit damages for design patent infringement. But, Professor Sarah Burstein says the four factor approach “is built on a legally and logically flawed foundation and … [the] proposed test–like any other multi-factor, factual inquiry–will increase the cost and complexity of design patent litigation without being likely to produce more just or more predictable outcomes.”

Instead, Burstein proposes an alternative method of determining the relevant article in her paper titled, The “Article of Manufacture” Today. There she makes the case that courts should adopt a historical definition of “article of manufacture.” After reviewing the history of the term she concludes:

…for a design patent claiming a design for surface ornamentation, the relevant article should be deemed to be whatever article the design was printed, painted, cast, or otherwise placed on or worked into. For a design patent that claims a design for a configuration or a combination of both configuration and surface ornamentation, the relevant article should be deemed to be the article whose shape is dictated by the claimed design.

She explains an article of manufacture should be “interpreted to refer to a tangible item made by humans that has a unitary structure and is complete in itself for use or for sale….” She also asserts that, historically, machines and compositions of matter should excluded from “articles of manufacture.”

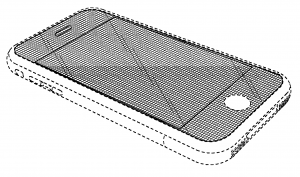

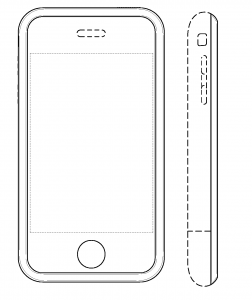

She further says that if courts feel “compelled to include machines in the category of ‘articles of manufacture,’ they should treat the exterior housings or shells of the machines as the relevant article because it is manufactured and could be sold separately.”

Burstein’s approach will be easier and cheaper to apply than the four factor test. And, Burstein argues the awards will “better reflect the designer’s actual contribution without providing too much of a windfall to the most design patentees.”

In a 2016Â

In a 2016Â

The importance of the wording of a patent claim is paramount. And, even the capitalization of the words of the claims can matter as shown in the case ofÂ

The importance of the wording of a patent claim is paramount. And, even the capitalization of the words of the claims can matter as shown in the case of