“[He] requested that he and his team be allowed to spend some time alone with the prototype, during which he photographed it without permission.”

Inventors and businesses are often concerned that their invention or technology will be stolen or copied in the marketplace. However, keeping an invention secret is not always an option. If bringing the invention to market requires disclosing the invention to the public, then secrecy is not an option. But neither, in such case, is keeping it locked up in the lab or under the mattress–if commercial exploitation of the invention is desired.

Inventors and businesses are often concerned that their invention or technology will be stolen or copied in the marketplace. However, keeping an invention secret is not always an option. If bringing the invention to market requires disclosing the invention to the public, then secrecy is not an option. But neither, in such case, is keeping it locked up in the lab or under the mattress–if commercial exploitation of the invention is desired.

There are at least two ways to protect yourself when interacting with another about the invention: (1) file a patent application on the invention beforehand, (2) enter into a favorable and strong nondisclosure agreement, or (3) both.

However, there are rarely guarantees. Even with a nondisclosure agreement agreement in place things can still go sideways, as allegedly happened to Mr. Hrabal when he interacted with Goodyear.

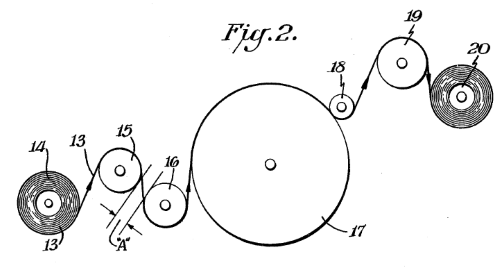

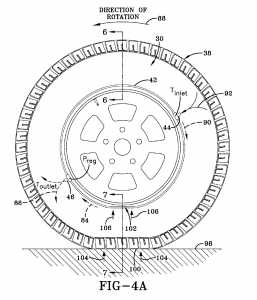

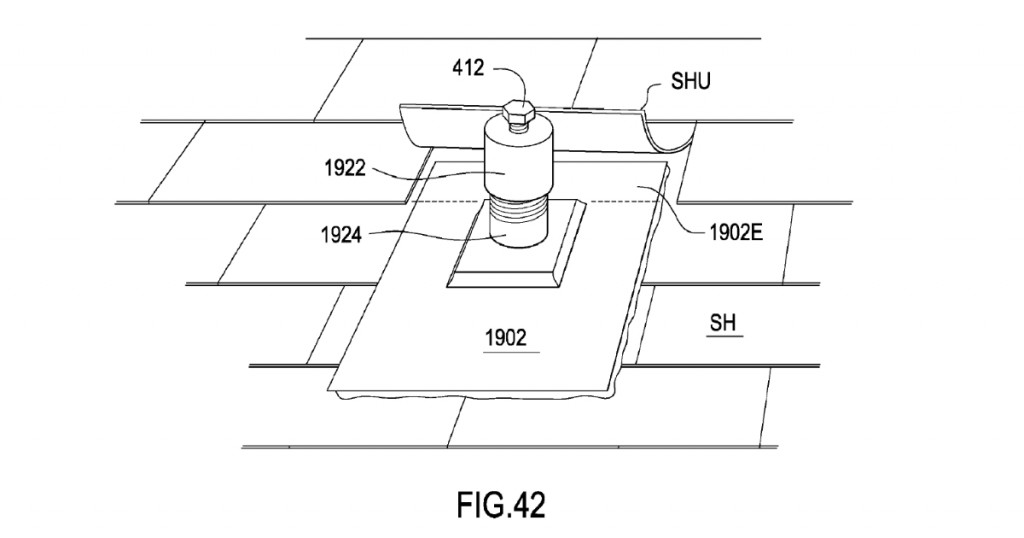

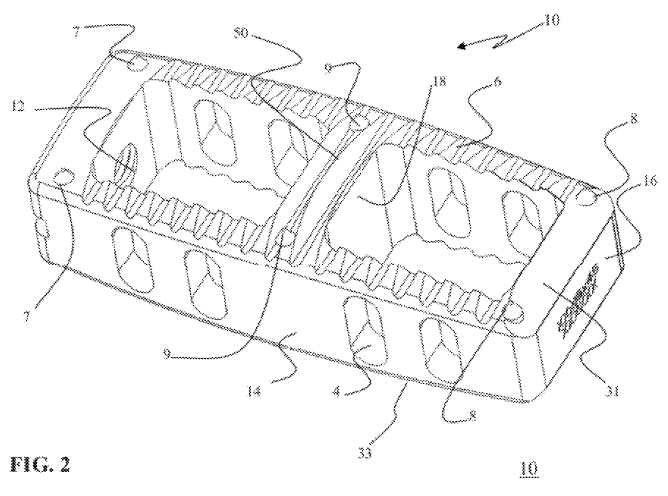

Mr. Hrabal’s complaint alleges the following in the case of Coda Development v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, 2018-1028 (Fed. Cir. 2019). In 2008, Mr. Hrabal invented a self-inflating tire (SIT) technology. General Motors expressed an interest and wanted to involve Goodyear. Goodyear reached out to Coda Development, Mr. Hrabal’s company, requesting a meeting. Before the meeting the parties executed a nondisclosure agreement restricting use of information regarding the SIT Technology.

Then Coda and Goodyear met in 2009 for the first time and requested that Coda share information on the SIT technology. At a second meeting in 2009, Coda allowed Goodyear to examiner a functional prototype of the SIT technology. Also at this second meeting, Mr. Benedict of Goodyear, “requested that he and his team be allowed to spend some time alone with the prototype, during which he photographed it without permission.”

Following the second meeting in 2009, months passed without any communication from Goodyear. Mr. Benedict later in 2009 declined an invitation from Coda to restart communications over a dinner saying that a meeting “would be premature at this point.”

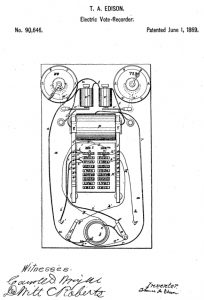

In December 2009, Goodyear applied, without Coda’s knowledge, for a patent titled “Self-Inflating Tire Assembly” naming Mr. Benedict as an inventor, which became U.S. Patent 8,042,586.

Coda assumed that Goodyear lost interest. But in 2012, Coda received an unsolicited email from a then ex-Goodyear employee that said “I am retired now from Goodyear and see in the news today that they have copied the SIT. Unfortunate. I though China companies were bad.”

Between 2012 and 2015 eleven other patents issued to Goodyear covering assemblies and methods for assembly of pumps and other devices used in self-inflating tires, which Coda claims cover confidential information Coda disclosed to Goodyear.

Goodyear denied Coda’s claims and denied that the Coda’s SIT technology was new. This case is only at the initial stage so the court has not made a final determination on these allegations.

What’s the take away here? Does one forego opportunities with other companies even while taking precautions and having a good nondisclosure in place? Probably no.

One should take reasonable steps to protect their interests. But, these allegations illiterate that things could still go badly.Â

Could someone try to steal your invention? It’s possible. But that possibility probably should not stop you from trying to commercialize the invention after taking reasonable steps to protect yourself, particularly if the alternative of indefinite secrecy means that your invention might never get off the ground commercially.

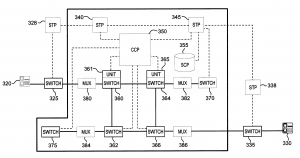

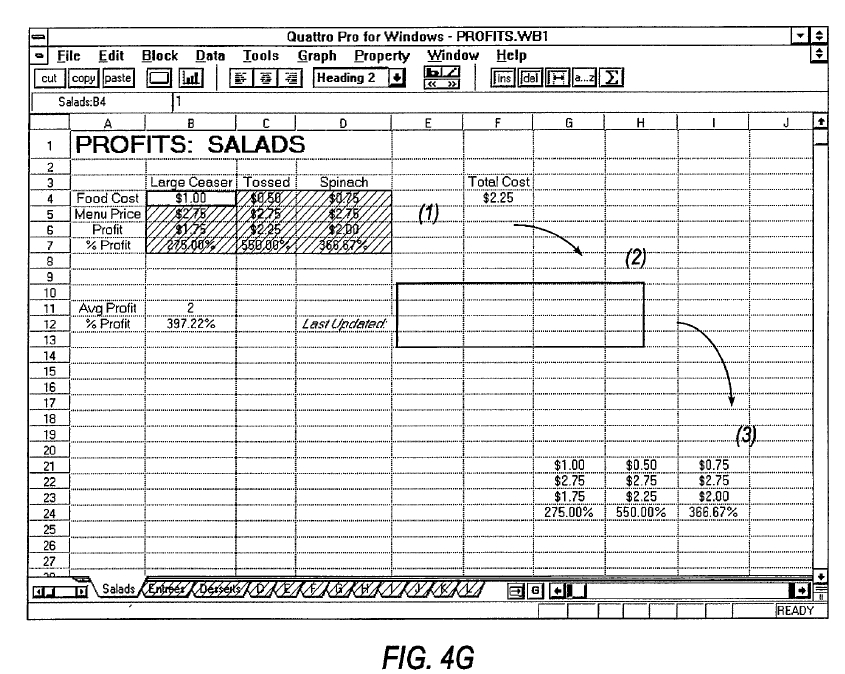

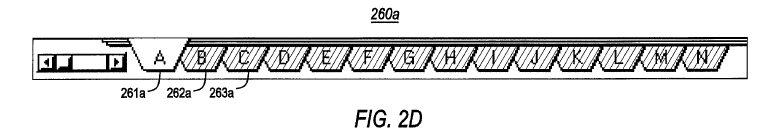

Drafting a patent application often involves describing the invention both broadly and in detail. But how can something be described both broadly and specifically?A decision in a case between Sprint and Time Warner Cable illustrates one way.

Drafting a patent application often involves describing the invention both broadly and in detail. But how can something be described both broadly and specifically?A decision in a case between Sprint and Time Warner Cable illustrates one way.

It is not surprising that the content of a patent application is important. Sometimes the description of something as simple as a washer is important to obtaining a valid patent.

It is not surprising that the content of a patent application is important. Sometimes the description of something as simple as a washer is important to obtaining a valid patent.

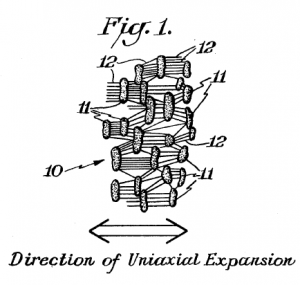

When an invention proceeds contrary to the accepted wisdom in the prior art, this is a strong indication that the invention is not obvious in view of the prior art.

When an invention proceeds contrary to the accepted wisdom in the prior art, this is a strong indication that the invention is not obvious in view of the prior art.