When an invention proceeds contrary to the accepted wisdom in the prior art, this is a strong indication that the invention is not obvious in view of the prior art.

When an invention proceeds contrary to the accepted wisdom in the prior art, this is a strong indication that the invention is not obvious in view of the prior art.

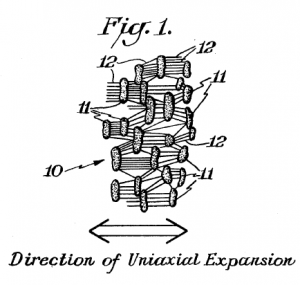

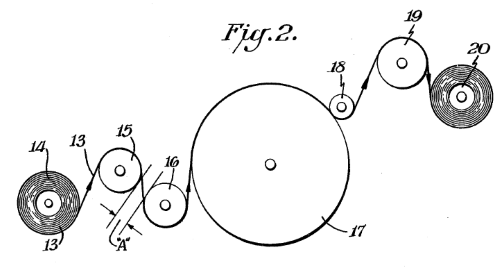

The case of W.L. Gore & Assocs. v. Garlock, Inc., 721 F.2d 1540, 1552 (Fed. Cir. 1983) demonstrates this principle. This is an old case from 1983, but the principle discussed today from the case is still valid. W.L. Gore & Associates (Gore) sued Garlock for infringing claims 3 and 19 of U.S. Patent 3,953,566 (the ‘566 patent). The ‘566 patent was directed to a method of making high crystalline polytetrafluorethylene (PTFE), such as might be used as tape. PTFE is known by the trademark TEFLON. PTFE tape had been sold as thread seal tape, i.e., tape used to keep pipe joints from leaking.

Dr. Gore of W.L. Gore & Associates experienced unsintered PTFE tape breakage problems in its tape stretching machine. Dr. Gore Experimented with heating and stretching of high crystalline PTFE rods. But the rods broke even when slowly and carefully stretching them a relatively small amount.

The conventional wisdom in the art taught that breakage could be avoided only by slowing the stretch rate or by decreasing the crystalline content. But contrary to this teaching, Dr. Gore discovered that stretching the PTFE rods as fast as possible enabled him to stretch them to more than ten times their original length with no breakage. Further, the rod diameter remained about the same through out the length and the rapid stretching transformed the the hard, shiny rods into rods of a soft, flexible material.Â

Ultimately, the appeals court concluded that claims 3 and 19 of the ‘566 patent were not obvious because Dr. Gore’s invention for making high crystalline PTFE proceeded contrary to accepted wisdom in the art.

If you can establish that your invention proceeds contrary to the accepted wisdom in the relevant art, then an obviousness rejection may be overcome on that basis.