When an invention possesses or provides unexpected results, this is often sufficient to show the invention is not obvious.

The case of Allergan, Inc. v. Sandoz Inc., 796 F.3d 1293 (Fed. Cir. 2015) demonstrates this principle. Allergen sued Sandoz among others alleging infringement of five patents directed a drug and treatment for glaucoma. The defendants asserted that the patents were invalid. Each of the asserted claims required a composition comprising 0.01% bimatoprost and 200 ppm benzalkonium chloride (BAK).Â

Prior treatments for glaucoma included using .03% bimatoprost and 50 ppm BAK. Prior art U.S. Patent 5,688,819 (Woodward) reference disclosed a composition comprising 0.001% to 1% bimatoprost and 0 to 1000 ppm of preservative, including BAK.

Therefore Woodward disclosed a range that covered the claimed composition. When that occurs the question is whether there would have been a motivation to select the claimed composition from the prior art ranges.

The court found that the prior art taught that BAK should be minimized in ophthalmic formations to avoid safety problems.  BAK was known to cause increased IOP, hyperemia, dry eye, and damage to corneal cells, and to exacerbate other eye disorders. Therefore the prior art taught away from increasing BAK from 50 ppm to 200 pmm.

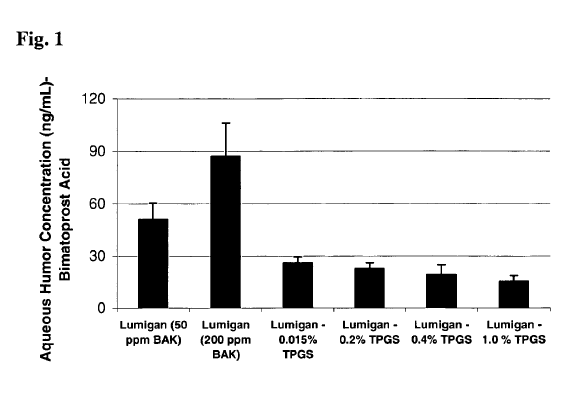

Further, the prior art taught that 200 ppm BAK would either have no impact on permeability of bimatoprost or decrease it. But Allergan’s inventors surprisingly determined that the opposite was true, 200 ppm BAK enhanced the permeability of the bimatoprost. The court concluded that his unexpected difference in kind supported nonobviousness of the claimed invention.

Moreover, the court found that the prior art taught that reducing bimatoprost from 0.03% to 0.01% resulted in reduced efficiency, but did not reduce red eye (hyperemia). However, the claimed, which comprises 0.01% bimatoprost and 200 ppm BAK, formulation unexpectedly maintained the IOP-lowering efficacy of Lumigan 0.03% (Allergen’s prior product), while exhibiting reduced incidence and severity of hyperemia (red eye), even though the prior art taught that BAK could cause hyperemia at high concentrations.

The court concluded that the results of the claimed formulation constituted an unexpected difference in kind, that is, “the difference between an effective and safe drug and one with significant side effects that caused many patients to discontinue treatment.” These unexpected results supported the conclusion that the challenged patent claims were not obvious in view of the prior art.

Therefore, when facing an obviousness rejection or challenge, look to see if you can show that the invention possesses or provides unexpected results in the art.

The five patents asserted in this case are: U.S. Patents 7,851,504, 8,278,353, 8,299,118, 8,309,605, and 8,338,479.