Anascape sued Nintendo alleging that Nintendo’s game controller infringed U.S. Patent 6,906,700Â (the ‘700 patent). Nintendo challenged the ‘700 patent asserting that it did not comply with the written description requirement of 35 USC 112.

Anascape sued Nintendo alleging that Nintendo’s game controller infringed U.S. Patent 6,906,700Â (the ‘700 patent). Nintendo challenged the ‘700 patent asserting that it did not comply with the written description requirement of 35 USC 112.

The written description requirement provides the “that specification [of the patent/patent application] shall contain a written description of the invention, and of the manner and process of making and using it…”

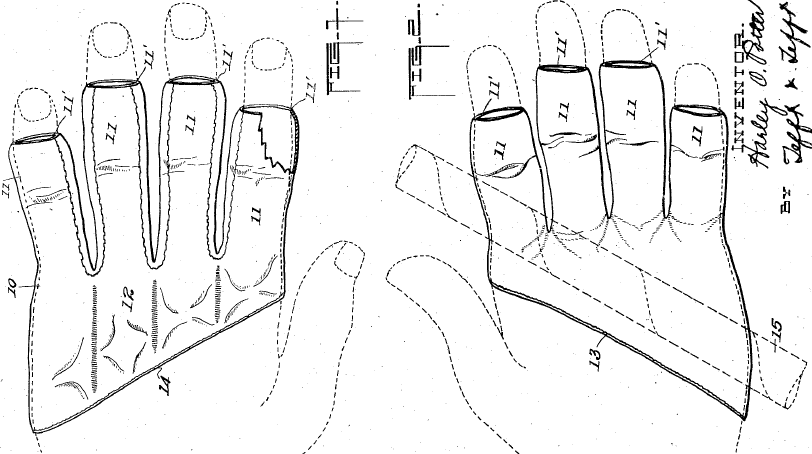

The claims of the ‘700 patent were directed to a controller that received multiple inputs that were together operable in six degrees of freedom. But, the ‘700 patent was issued from a continuation application that claimed priority to a prior parent application (that became U.S. Patent 6,222,525 (the ’525 patent)). The ‘525 patent only disclosed a single input member (controller) capable of movement in six degrees of freedom. The ‘525 patent repeatedly referenced (over twenty times) the input member as a single input member. It also disparaged the prior art devices having multiple input members.

The court concluded that the ‘525 patent did not disclose multiple input members, but rather only a single input member. Therefore, the ‘700 patent failed to meet the written description requirement for multiple inputs to obtain the benefit of the filing date of the ‘525 patent.

Intervening prior art existed between the filing of the ‘525 patent and the filing of the ‘700 patent. Therefore, without the benefit of the earlier filing date of the ‘525 patent, the claims of the ‘700 patent were invalid and Nintendo avoided infringement.

Given the repeated use of “single input member” and the disparagement of multiple input members, it appears that the original ‘525 patent was intended to be limited to only a single input member. That is, it was not a drafting error that a variation of the invention with multiple input members was omitted.

Nevertheless, this case demonstrates why when drafting a patent application, it is important to account for multiple variations of the invention. You should think about what components can be multiplied and describe those in a manner that can account for such versions of the invention. The use of exclusively restrictive language like “single” or “only one” may confine a patent resulting on your invention.

The written description requirement is separate, and arguably more stringent, than the enablement requirement. Further, the courts have been strict in asserting that it is not enough to assert that claimed variation is obvious in light of what was disclosed. Rather, to be safe, the variations should be clearly explained in the description.

Citation: Anascape, Ltd. v. Nintendo of Am., Inc., 601 F.3d 1333 (Fed. Cir. 2010)

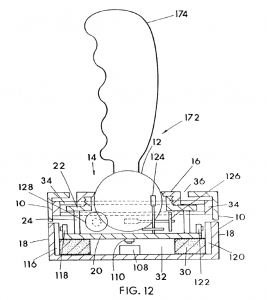

Divided infringement occurs when no one party actually performs all of the steps of a patent claim. For example, one party performs some of the steps and another party performs the remaining steps. One way to solve this problem is to draft patent claims such that one party will likely perform all of the claimed steps.

Divided infringement occurs when no one party actually performs all of the steps of a patent claim. For example, one party performs some of the steps and another party performs the remaining steps. One way to solve this problem is to draft patent claims such that one party will likely perform all of the claimed steps. Automotive Technologies International (ATI) sued numerous vehicle and parts manufacturers including BMW and Delphi Automotive Systems for infringing

Automotive Technologies International (ATI) sued numerous vehicle and parts manufacturers including BMW and Delphi Automotive Systems for infringing

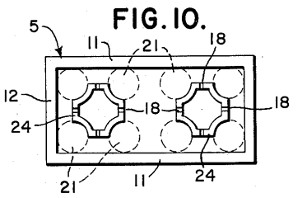

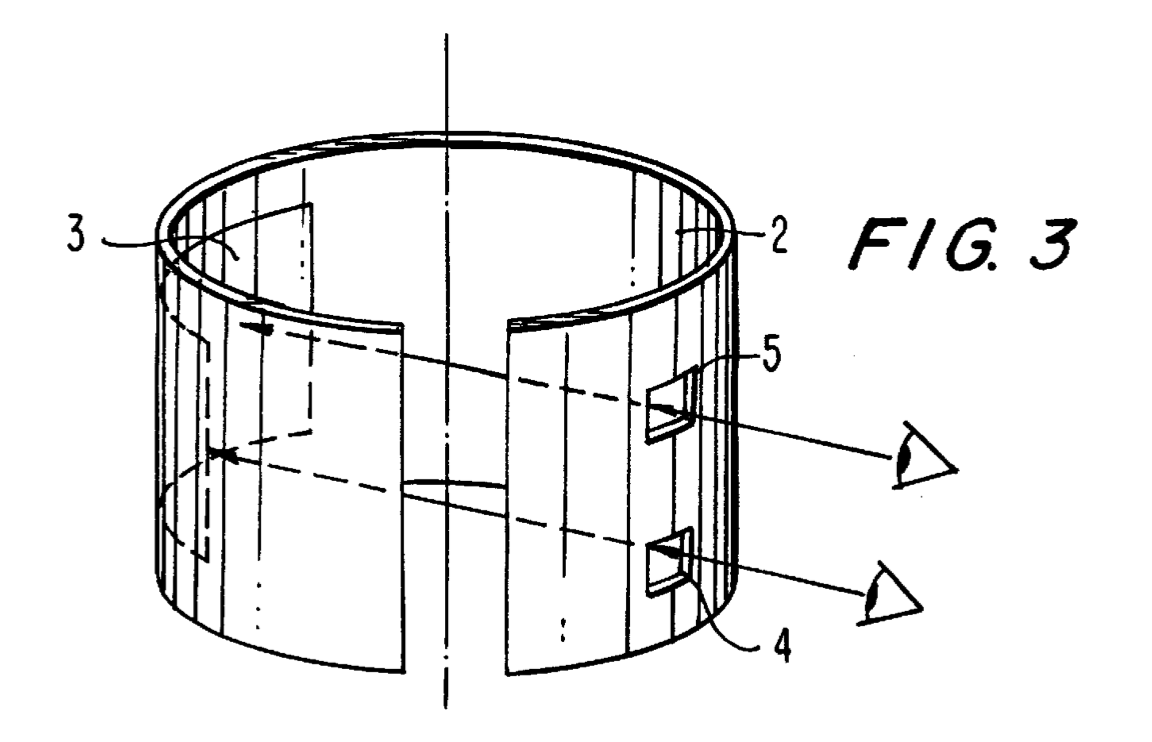

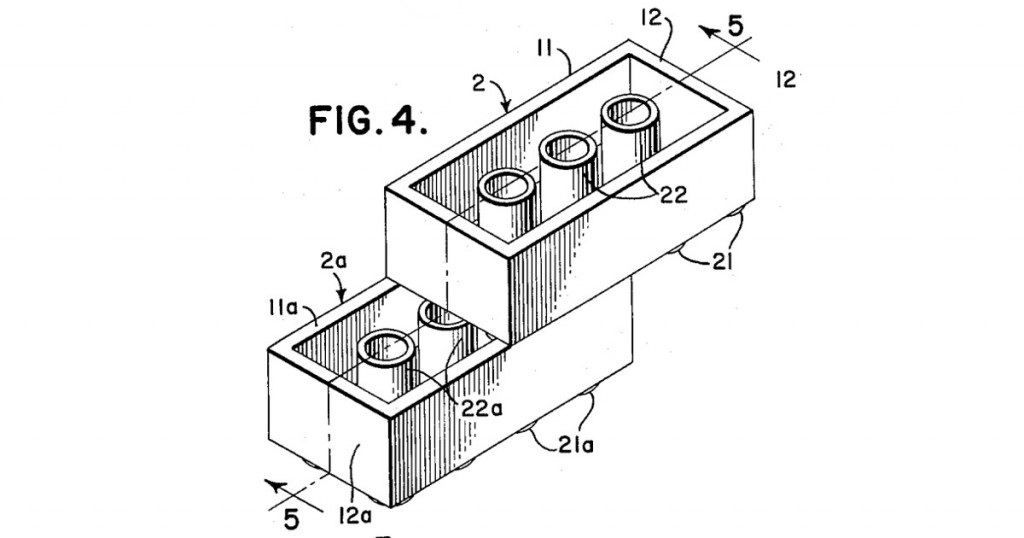

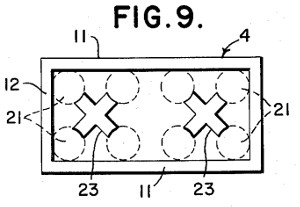

Â Figure 10 shows an alternative block having somewhat star-snapped projections 24.

Figure 10 shows an alternative block having somewhat star-snapped projections 24.