Selling or transferring ownership of a U.S. patent or patent application must be carried out by a written document called an assignment. See 35 USC 261. Below I review four common provisions of a patent/patent application assignment and then I explain the benefits of having an assignment notarized and recorded at the USPTO.

1. Transfer of Ownership

The ownership transfer clause effects the transfer of the invention and the patent application. One example ownership transfer clause is: “In consideration of good and valuable consideration, the receipt of which is hereby acknowledge, the entire right, title, and interest in the invention by [Inventor(s) Name] (“Assignor”) of the [Title of Invention] (“Invention”) and in the application for Letters Patent of the United States therefor, identified by serial number ________ and filing date ________ (“Application”), and in any reissue of any Letters Patent that may be granted upon the Application are hereby assigned by Assignor to [Recipient/Assignee] [an individual / a Corporation/LLC organized under the laws of [State]] having an address at _____________ (“Assignee”).” Notice that this clause transfers ownership of the invention and the patent application for that invention.

2. Geographic Scope

A provision defining the geographic scope of the assignment is desirable. Often an assignment is intended to apply worldwide to allow the receiving party (i.e. the Assignee) to file patent application on the invention in any foreign country. Therefore, an assignment might provide, “The assigned rights include all worldwide rights to file any international patent applications, foreign patent applications, foreign design patent applications, utility model application, or similar industrial property rights for the Invention…”

3. Continuations and Divisionals

Patent applications occasionally include and claim more than one invention. The Patent Office may issue a restriction requirement, where the applicant must elect among the multiple inventions in the application. The unelected inventions can be pursued in a separately filed divisional application. The divisional application can be thought of a “child” application of the original “parent” application.

A continuation patent application and a continuation-in-part patent application are other types of “child” patent applications that the patent owner might want to file and therefore will want to right to file. It is desirable for the assignment to expressly authorize the Assignee (receiver) to file divisional, continuation, and continuation-in-part patent applications based on the original application.

4. Obligation to Assist and Execute

In the U.S. an inventor signed declaration is usually filed with a patent application. There are provisions for accounting for situations were an inventor declaration cannot be obtained. However, generally, you want to have in inventor declaration filed in or with your patent application. Therefore, it is desirable to including in an assignment a written obligation for the inventor to execute all documents that the Assignee (recipient) desires in connection with the the patent application and any continuation, divisional, or other patent application concerning the invention.

Further, if the resulting patent is involved in a lawsuit, the patent owner will want the inventor to assist the patent owner in asserting or defending the patent. Therefore, the assignment should include a clause requiring the inventor to execute documents requested by the patent owner in connection with any lawsuit, reexamination, reissue, inter partes reexam, or other proceeding related to the patent. It would further be desirable for the assignment to require the inventor to assist and cooperate, beyond executing documents, with the patent owner in any such lawsuit or proceeding. For example, the patent owner may need the Inventor to testify about the invention.

Notary

The signatures of an assignment of a patent or patent application should notarized. 35 USC 261 provides a presumption that when signatures are notarized the assignment “shall be prima facie evidence of the execution of the an assignment, grant, or conveyance of a patent or application for patent.” In other words, it will be harder for someone to challenge the validity of the signatures. Therefore the assignment will be stronger.

Recording at USPTO

An assignment should be recorded at the USPTO to gain the benefit of 35 USC 261, which provides, “An interest that constitutes an assignment, grant, or conveyance shall be void as against any subsequent purchaser or mortgagee for valuable consideration, without notice, unless it is recorded in the Patent and Trademark Office within three months from its date or prior to the date of such subsequent purchase or mortgage.” This statute protect you when you record the assignment against problems if the inventor or prior patent owner sells the same invention to another party later.

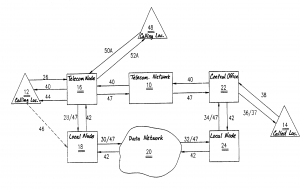

The importance of the wording of a patent claim is paramount. And, even the capitalization of the words of the claims can matter as shown in the case of AIP Acquisition LLC v. Cisco Systems, Inc., No. 2016-2371 (Fed. Cir. 2017).

The importance of the wording of a patent claim is paramount. And, even the capitalization of the words of the claims can matter as shown in the case of AIP Acquisition LLC v. Cisco Systems, Inc., No. 2016-2371 (Fed. Cir. 2017).