A patent infringer is liable to a patent owner for damages adequate to compensate the patent owner for infringement, but no less than a reasonable royalty for the use made of the invention by the infringer. 35 USC 284.

Traditionally, there are three ways of measuring compensatory damages for patent infringement: (1) lost profits, (2) established royalty, or (3) a reasonable royalty. Today I’m going to discuss lost profit damages.

Lost Profits

In order to recover lost profits, the patent owner must “show ‘causation in fact,’ establishing that ‘but for’ the infringement, he would have made additional profits.” Wechsler v. Macke Int’l Trade, Inc., 486 F.3d 1286, 1293 (Fed. Cir. 2007). The “but for” causation asks, if the infringement had not occurred, would the patent owner made the alleged lost profits? If the patent owner is not selling a product, then usually there is no lost profits, except if the patent owner has the ability to manufacture and market the product, but for some legitimate reason is not. Id.Â

Courts have allowed patent owners to present “market reconstruction theories showing all of the ways in which they would have been better off in the ‘but for world,’ [a world without the infringement] and accordingly to recover lost profits in a wide variety of forms.” Grain Processing Corp. v. Am. Maize-Products Co., 185 F.3d 1341, 1350 (Fed. Cir. 1999)

Lost profits can arise from a showing that but for the infringement the patent owner would have (1) made greater sales, (2) charged higher prices, or (3) incurred lower expenses.

Courts sometimes use the Punduit test to determine whether the patent owner proved causation for lost profit damages. The Punduit test requires the patent owner to establish: (1) demand for the patented product; (2) absence of acceptable non-infringing substitutes; (3) manufacturing and marketing capability to exploit the demand; and (4) the amount of the profit it would have made. Rite-Hite Corp. v. Kelley Co., 56 F.3d 1538, 1545 (Fed. Cir. 1995) (citing Panduit Corp. v. Stahlin Bros. Fibre Works, 575 F.2d 1152, 1156 (6th Cir. 1978)).Â

If there are only two suppliers for the product at issue in the relevant market, the patent owner and the accused infringer, the first two Punduit test factors collapse into one in the two-supplier test. Under the two-supplier test a patent owner must show: (1) the relevant market contains only two suppliers, (2) its own manufacturing and marketing capability to make the sales that were diverted to the infringer, and (3) the amount of profit it would have made from these diverted sales. Micro Chem., Inc. v. Lextron, Inc., 318 F.3d 1119, 1124 (Fed. Cir. 2003).Â

Lost Sales or Diverted Sales

When lost sales are the basis for lost profits, the interaction of the patent owner and the infringer in the market is important. “If the patentee and infringer do not sell their products in the same market segment, “but for” causation cannot be demonstrated.” Crystal Semiconductor Corp. v. Tritech Microelectronics Int’l, Inc., 246 F.3d 1336, 1360 (Fed. Cir. 2001)

Reduction in Prices or “Price Erosion”

A reduction of prices by the patent owner caused by the infringing competition is a proper ground for lost profit damages. The patent owner must show that “but for” infringement, it would have sold its product at a higher price. Id.

In a later post I will discuss royalties damages for patent infringement.

Update: A post on established royalties for patent infringement.

Update: A post on reasonable royalties for patent infringement.

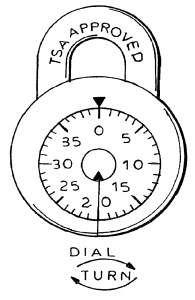

When describing an invention in a patent application, every inventor must disclose the best mode of carrying out the invention, known to the inventor. This requirement is found at

When describing an invention in a patent application, every inventor must disclose the best mode of carrying out the invention, known to the inventor. This requirement is found at

Anascape sued Nintendo alleging that Nintendo’s game controller infringed

Anascape sued Nintendo alleging that Nintendo’s game controller infringed  Divided infringement occurs when no one party actually performs all of the steps of a patent claim. For example, one party performs some of the steps and another party performs the remaining steps. One way to solve this problem is to draft patent claims such that one party will likely perform all of the claimed steps.

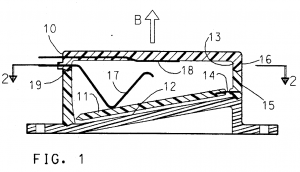

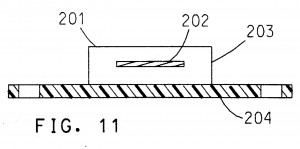

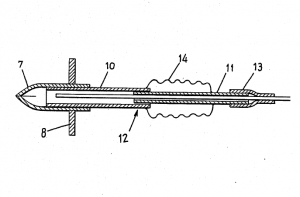

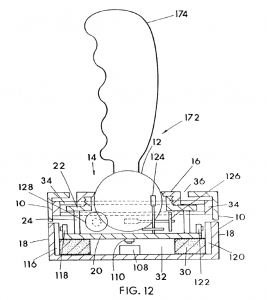

Divided infringement occurs when no one party actually performs all of the steps of a patent claim. For example, one party performs some of the steps and another party performs the remaining steps. One way to solve this problem is to draft patent claims such that one party will likely perform all of the claimed steps. Automotive Technologies International (ATI) sued numerous vehicle and parts manufacturers including BMW and Delphi Automotive Systems for infringing

Automotive Technologies International (ATI) sued numerous vehicle and parts manufacturers including BMW and Delphi Automotive Systems for infringing