Automotive Technologies International (ATI) sued numerous vehicle and parts manufacturers including BMW and Delphi Automotive Systems for infringing US patent 5,231,253 on side impact crash sensors for deploying an air bag. The court of appeals determined that the patent was invalid for failing to enable the claimed invention in Auto. Techs. Int’l, Inc. v. BMW of N. Am., Inc., 501 F.3d 1274 (Fed. Cir. 2007).

Automotive Technologies International (ATI) sued numerous vehicle and parts manufacturers including BMW and Delphi Automotive Systems for infringing US patent 5,231,253 on side impact crash sensors for deploying an air bag. The court of appeals determined that the patent was invalid for failing to enable the claimed invention in Auto. Techs. Int’l, Inc. v. BMW of N. Am., Inc., 501 F.3d 1274 (Fed. Cir. 2007).

The law requires that your patent application describe your invention to such a level of detail so as to enable one who’s skilled in the art to  make and use the invention, without undue experimentation. This is known as the enablement requirement. The relevant statute states that every patent must describe “the manner and process of making and using [the invention], in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art to which it pertains, or with which it is most nearly connected, to make and use the [invention].” 35 USC 112.

This is part of the patent bargain. You tell the world how to make and use the invention and the government grants you a limited monopoly.

It is not uncommon for an inventor to leave out details of the invention that he/she thinks are well known in the art. But you want to draft a application that is well within the knowledge of one skilled in the art area and no where near the boundary of what one skilled in the art knows. Therefore, you often want to explain concepts and details that one skilled in the art already knows. When in doubt, provide more detail.

This is true because when an inventor chooses to rely upon general knowledge in the art to render his/her disclosure enabling, the inventor bears the risk on this issue of whether those of ordinary skill in that can be expected to possess or know where to obtain this knowledge. In re Howarth, 654 F.2d 103 (CCAP 1981).  “To avoid the risk, [he/she] need only set forth the information in his specification…” And you should want to avoid this risk, as the ATI case demonstrates.

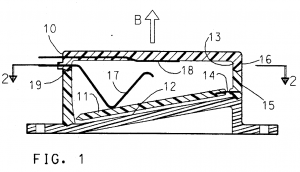

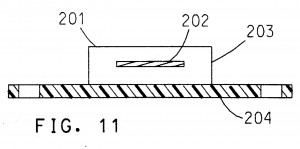

In the ATI case, the patent disclosed two impact crash sensors, one was a mechanical sensor and the other was an electronic sensor. The patent described the mechanical sensor at length (figure 1). But it only provided one short paragraph and one “conceptual” drawing (figure 11) about the electronic sensor. The court found the thin disclosure of an electronic sensor was not sufficient to inform one skilled in the art how to make the invention with the electronic sensor. Since the claims were broad enough to cover both mechanical and the non-enabled electronic sensors, all of the patent claims were found invalid.

The description of the electronic sensor in the patent failed to disclose a structure or circuitry  for the sensor. The court found that ATI could not rely on prior art knowledge of front electronic impact sensors because ATI stated that the novel aspect of the invention was the side impact sensor. The court said, “given that the novel aspect of the invention is a side impact sensor[], it is insufficient to merely state that known technologies case be used to create an electronic sensor. Moreover, there were no electronic sensors in existence to detect side impact crashes at the time the application was filed.

Also, the court stated electronic sensors are of the same class of technology as mechanical ones: “Electronic side impact sensors are not just another known species of genus consisting of sensors, but are a distinctly different sensor compared with the well-enabled mechanical side impact sensor [described]…”

As the ATI case demonstrates, it is best not to get close to the line between what is and is not enough detail to enable a person skilled in the art to make and use your invention. Instead you should spend the time to provide the level of detail, with respect to each variation of the invention, so there can be no question. And that often involves describing details known to one skilled in the art.