In order to obtain a patent on an invention, the invention must not be obvious in view of the prior art. This requirement is provided in 35 USC 103, which states:

A patent for a claimed invention may not be obtained, notwithstanding that the claimed invention is not identically disclosed as set forth in section 102, if the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art are such that the claimed invention as a whole would have been obvious before the effective filing date of the claimed invention to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which the claimed invention pertains.

Obviousness determinations require a multifaceted consideration of the invention and the prior art.

The framework for obviousness determinations is provided by the Supreme Court in Graham v. John Deere Co., 383 U.S. 1 (1966). When considering obviousness one must (1) determine the scope and content of the prior art, (2) ascertain differences between the prior art and the claims at issue (the claimed invention), and (3) resolved the level of ordinary skill in the pertinent art. Obviousness or nonobviousness of the invention is determined against this framework.

Further, the USPTO fact finder must provide a rationale of why the invention is obvious. The Supreme Court in KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex Inc., 550 U.S. 398, 415-421 (2007) made it easier for the USPTO to reject inventions as obvious. Prior to KSR, one could argue that an obviousness rejection was inproper if there was not teaching, suggestion, or motiviation to combine the prior art references. But, the court said “The obviousness analysis cannot be confined by a formalistic conception of the words teaching, suggestion, and motivation, or by overemphasis on the importance of published articles and the explicit content of issued patents.” This opened the door to the use of additional rationales and evidence to support an obviousness rejection. And, this made life harder for some patent applicants.

After KSR, the USPTO reviewed several court cases and attempted to distill possible non-limiting example rationales that could support an obviousness determination. Therefore, even if there was no teaching, motivation, or suggestion, the patent examiner might be able to rely on the following other rationales:

- Combining prior art elements according to known methods to yield predictable results;

- Simple substitution of one known element for another to obtain predictable results;

- Use of known technique to improve similar devices, methods, or products in the same way;

- Applying a known technique to a known device, method, or product ready for improvement to yield predictable results;

- Choosing from a finite number of identified, predictable solutions, with a reasonable expectation of success; or

- Known work in one field of endeavor may prompt variations of it for use in either the same field or a different one based on design incentives or other market forces if the variations are predictable to one of ordinary skill in the art. [MPEP 2143]

These rationales all rely on the predictability of the results of combining references. If the proposed combination would not have been recognized by one skilled in the art to produce predictable results, then these rationales should not apply.

Further, if one takes the example rationales of MPEP 2143 and considers them broadly it is possible that one could conclude that many patentable inventions are actually unpatentably obvious. However, you can’t take the rationales at face value because there are a host of rebuttal circumstances or circumstances where some of rationales don’t apply or would be applied only narrowly. In other words, don’t over generalize the MPEP 2143 rationales and conclude your invention is obvious.

For example, the following circumstances may prevent the combination of references in an obviousness rejection:

- one of the references teaches away from the combination of the other references,

- the proposed modification or combination will render the reference being modified unsatisfactory for its intended purpose,

- the proposed modification would change the principle operation of the prior art invention being modified, or

- the invention proceeds contrary to accepted wisdom in the art.

[See In re Grasselli, 713 F.2d 731, 743 (Fed. Cir. 1983), MPEP 2145(X)(D); In re Gordon, 733 F.2d 900 (Fed. Cir. 1984); MPEP 2143(V); In re Ratti, 270 F.2d 810, 813 (CCPA 1959); MPEP 2143(VI); In re Hedges, 783 F.2d 1038 (Fed. Cir. 1986); MPEP 2145(X)(D)(3).]

But these are just a few examples.

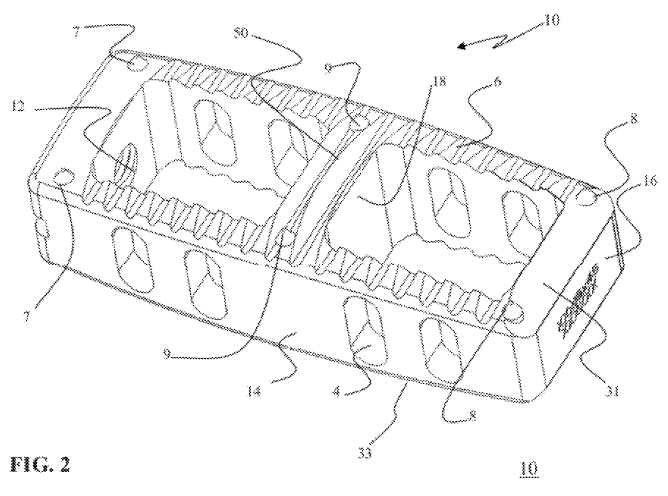

Further, the USPTO’s rationale for combining prior art references in an obviousness rejection must have an adequate evidentiary basis and there must be a connection between the rationale and the motivation to combine references in the obviousness rejection. In re NuVasive, Inc., 842 F.3d 1376, 1382 (Fed. Cir. 2016); MPEP 2143. If the USPTO fails to meet these requirements the obviousness rejection can be improper.

In addition, so-called “secondary considerations” can be important to show nonobviousness. Secondary considerations may include: (1) commercial success of the claimed invention, (2) a long felt but unsolved need, or (3) failure of others.

As you can see there are several factors and elements to consider when attempting to establish obviousness or rebut it. And, the USPTO, district courts, and appeal courts, often disagree about whether a particular invention is obvious. For example, in Novartis AG v. Noven Pharmaceuticals Inc., 853 F. 3d 1289 (Fed. Cir. 2017), the PTAB of the USPTO found the challenged claims of U.S. Patent Nos. 6,316,023 and 6,335,031 were invalid as obvious. But, based on the same evidence, a prior District court found the claims of same patents were not obvious. The different results for the same patents on the same evidence were due in part to the different standards used by the PTAB and the district court. However, these varying results say something about the difficulty in applying and predicting whether an invention is obvious.

Nevertheless, obviousness of an invention can be assessed before a patent application is filed, usually after a patent novelty search is performed. And there are several possible angles for overcoming obviousness rejections at the USPTO.

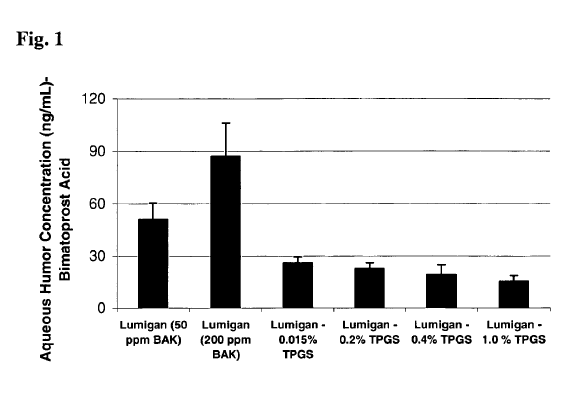

When an invention proceeds contrary to the accepted wisdom in the prior art, this is a strong indication that the invention is not obvious in view of the prior art.

When an invention proceeds contrary to the accepted wisdom in the prior art, this is a strong indication that the invention is not obvious in view of the prior art.

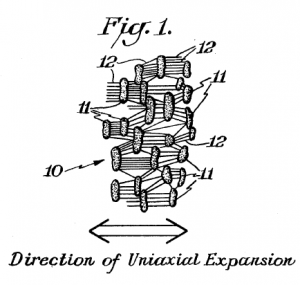

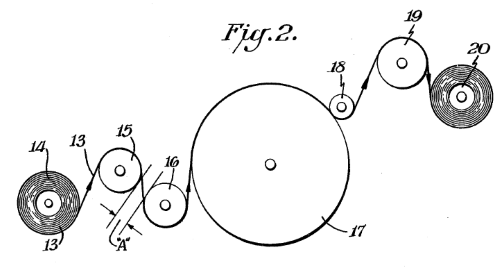

When the USPTO rejects patent claims based on alleged obviousness, it often combines two or more prior art references to make the rejection. This combination may be challenged if one of the

When the USPTO rejects patent claims based on alleged obviousness, it often combines two or more prior art references to make the rejection. This combination may be challenged if one of the