Can I patent this invention? One of the first steps in the patent process is to determine whether you can obtain a patent on the invention. The heavy lifting of this determination is a patentability search, also known as a patent novelty search. The purpose of the search is to give you information on whether your invention is new and therefore patentable. Can you do that search yourself?

Can I patent this invention? One of the first steps in the patent process is to determine whether you can obtain a patent on the invention. The heavy lifting of this determination is a patentability search, also known as a patent novelty search. The purpose of the search is to give you information on whether your invention is new and therefore patentable. Can you do that search yourself?

Searching Yourself v. Professional Searching

Yes, but patent searching is an art that you get better at with repeated practice. Therefore, a professional patent searcher is likely to uncover results that you did not find given the professional searcher’s experience, access to search tools, and knowledge of searching techniques.

However, you may like to perform patent searching on your own because you could identify relevant prior art references, which if such references disclose all the features of your invention, would enable you to avoid the cost of hiring a professional patent searcher.

Yet, before concluding your invention is not patentable based on the results of your search, you should consult a patent attorney for advice as to whether you could obtain patent protection even in light of the prior art references you found. In some cases, results that appear to block your ability to obtain a patent can be overcome with the appropriate patent strategy and patent drafting approach.

Always Relevant Results

There is relevant prior art for almost every invention. Therefore, it is extremely unlikely (or impossible?) that a patent search will return no relevant prior art references. So when someone says they searched the patent office records and there is nothing like the invention, I know that there is more than nothing relevant. The issue is usually (1) that the search scope was not broad enough, or (2) the search simply did not locate the relevant results. In the first case, the search scope is usually not broad enough because the inventor/client does not realized the scope of relevant inventions. For example, if the invention is related to car horns, the search should not be limited to only car horns, but should extend to any vehicle horn, such as a truck horn, a boat/ship horn, tractor horns, motorcycle horns, possibly a bicycle horns or other non-motorized vehicles, possibly stationary horns, etc.

So, if your search uncovers nothing relevant, then you know you need to keep searching or hire a professional patent searcher.

To gain an understanding the search process we can look to the manual that the Patent Examiners follow when examining patent applications, which is titled, the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP). The MPEP provides the high level search approach: “(A) identifying the field of search; (B) selecting the proper tool(s) to perform the search; and (C) determining the appropriate search strategy for each search tool selected.” MPEP 904.02.

Problems With Text-Only Searching

That sounds pretty straight forward. Â The devil is in the details. Before getting to a more specific search strategy, let’s look at the warnings that the MPEP provides about text searching.

The MPEP warns against relying on text searching alone:

Text search can be powerful, especially where the art includes well-established terminology and the search need can be expressed with reasonable accuracy in textual terms. However, it is rare that a text search alone will constitute a thorough search of patent documents. Some combination of text search with other criteria, in particular classification, would be a normal expectation in most technologies.

[MPEP 904.02 (emphasis added)].

Text searching is keyword searching. Text searching is when you enter words into a search engine and the engine returns results having those words.

The problem with text searching is that a patent attorney can act as a lexicographer, that is the patent drafter can make up words, assign words meanings other than their normal meaning, and can use terms other than the common terms for a given part, component, or feature of the invention. This is what makes text-only searching problematic.

The MPEP discusses the difficulty in choosing the right textual terms to search for a given invention:

Examiners will recognize that it is sometimes difficult to express search needs accurately in textual terms. This occurs often, though not exclusively, in mechanical arts where, for example, spatial relationships or shapes of mechanical components constitute important aspects of the claimed invention. In such situations, text searching can still be useful by employing broader text terms, with or without classification parameters.

[MPEP 904.02Â (emphasis added)].

For example, U.S. Patent 5,185,953 is for a mouse trap. But the title of that patent is not “mouse trap,” but instead is “rodent extermination device.” Also, U.S. Patent 2,415,012 is for the Slinky toy. But that patent does not use the term “Slinky.” And, it’s title is “Toy and Process of Use.”

The MPEP provides one solution to the text-only search problem and that is a classification search:

The traditional method of browsing all patent documents in one or more classifications will continue to be an important part of the search strategy when it is difficult to express search needs in textual terms.

[MPEP 904.02Â ].

That’s right, for some inventions, it may be necessary or advisable to browse (e.g. look at) all patents within one or more classes. Looking at each patent within a classification avoids the lexicographer problem explained above, because browsing the drawings or other content of a patent document can identify relevant patents that might not be found by text searching.

It can be tedious and time consuming to browse all patents within one or more classes. This is especially true if you don’t have access to search tools that allow quickly viewing each patent and moving to the next. Regardless, depending on the type of invention, classification searching is likely necessary.

Patent Searching Framework

While classification searching is often needed, it can be difficult for a novice to be as effective searching the classification system as a professional searcher that has searched the classification system numerous times and has a familiarity with it.

Therefore, we can start with text searching to find relevant classes to look to. Alternatively, you can browse or search the classification scheme for relevant classes (skipping to step 8).

I suggest the following framework for searching:

- Brainstorm keywords describing the invention

- Perform keyword searching to identify some relevant patents

- Identify new keywords in found relevant patents, search with new keywords

- Review backward looking cited references and forward looking references

- Note the classes of the relevant patents

- Review class definitions of noted classes

- Review adjacent classes to the noted classes

- Search and browse CPC scheme for additional relevant classes

- Perform classification searches

- Optionally narrow classification search by keyword

- Keep searching

I’ll explain each step in detail.

1. Brainstorm keywords describing the invention

Create a list of keywords that describe the invention, including important features of the invention. From those keywords, look up synonyms to each a thesaurus. The identify search groupings of keywords for search queries.

Here are questions suggested by the USPTO to assist in developing a list of relevant keywords:

- What does the invention do? (Essential function of the invention)

- What is the end result? (Essential Effect or basic product resulting from the invention)

- What is it made of? (Physical structure and components)

- What is it used for? (Intended use)

Let’s say you wanted to find patents directed to a method of purchasing a product from an online store with one click. Amazon obtained such a patent, U.S. Patent 5,960,411 (“the ‘411 patent”) is popularly known as the Amazon one-click patent. If you search Google patents for “one click order” the ‘411 patent will be the first result. However, this is likely only because this is a famous patent that received a lot of media attention.

If this patent was not famous, you probably would not find it by searching “one click order.” Why? because nowhere in the patent does it say “one click.”  Instead it provides, for example, “The client system … displays an indication of an action (e.g., a single action such as clicking a mouse button) that a purchaser is to perform to order the identified item.”

Synonyms for “click” in this circumstance include action, act, selection, process, motion, operation, movement, activity, etc. Synonyms for single include one, only one, etc.

2. Perform keyword searching to identify some relevant patents

Now you can take those search terms and combine them to perform various searches in the patent databases.

What are the patent databases? First are the USPTO Patent and Published Patent Application databases. You can perform word searching via the web in those databases. However, patents from 1790 to 1975 are not text searchable. So text searching will not show any results for this time period. This is likely not a problem for newer technologies. However, many inventions have relevant prior art from these time periods. You can review the search options at the USPTO help page.

Another search tool is Free Patents Online (FPO), which is relatively fast. The patent documents are hyperlinked so you can navigate from one patent to the next rather quickly.

The problem with FPO, and with the USPTO tools, is that you can not quickly view the drawings of a patent. FPO and the USPTO do not show you thumbnail images of the drawings when you first get to the detail page for a particular patent. In FPO you have to click on the view PDF link and wait for the PDF to load in your browser. The same is true for the USPTO databases.

Google Patents is better at quickly showing images of the patents. The result list shows thumbnail images of the first page of each patent. When you select the patent, the patent detail page shows thumbnails of all the drawings. When looking to browse images, Google Patents makes the job easier than the USPTO or FPO.

Some have noted that Google’s patent database has holes, in that its missing patents know to exist. So, you should not rely exclusively on Google Patents for all of your searching. In general, it is good to use a mix of tools when patent searching for completeness.

3. Identify new keywords in relevant patents, search with new keywords

When you find a relevant patent document, review it to see if it uses terms related to your invention that you did not think of initially. Add those new terms to your search keywords and preform additional searching with those new terms.

4. Review backward looking cited references and forward looking references

U.S. patents and published patent applications (and many foreign patent documents) cite to other prior patents, patent applications, and publications. These backward looking citations to patent documents (also know as “references cited”) are made by the patent applicant or the patent examiner during the patent application process. Either the patent applicant or the patent examiner believed that the references cited were related to some aspect of the invention. Therefore, if you find a relevant patent, you should look to the references cited, which may also be relevant. Sometimes these references cited will be more relevant to your invention.

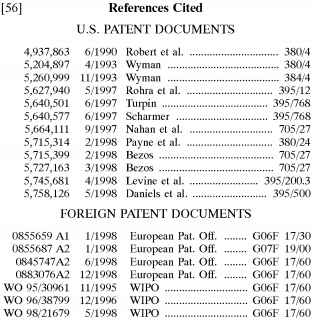

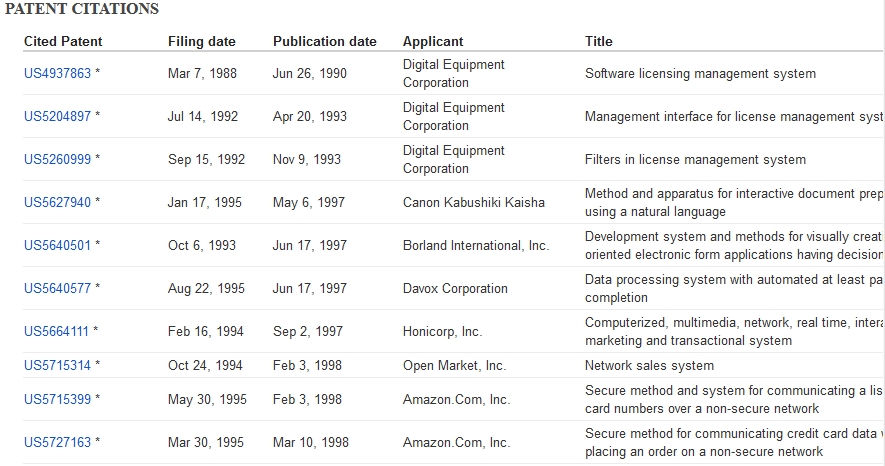

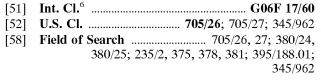

Below is a excerpt of the references cited from the front page of the ‘411 patent.

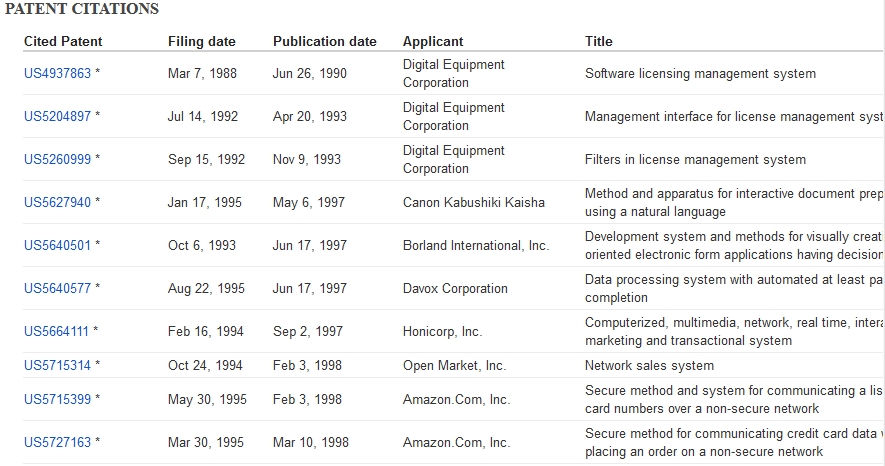

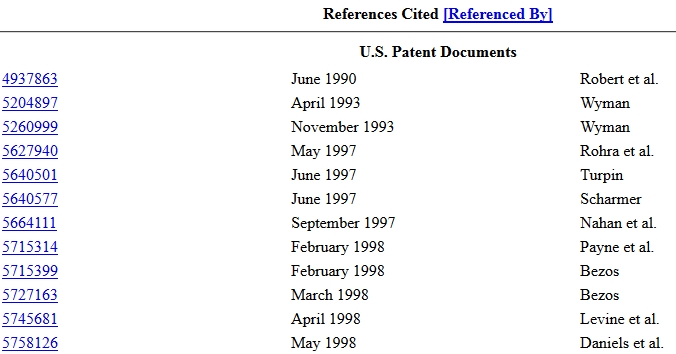

If the ‘411 patent was a relevant patent, you’d want to look at some or all of these references cited. The USPTO, Google patents, and FPO provide hyperlinks to each of the US patent documents cited. However, the USPTO does not provide the title for each reference cited. The title can be helpful in determining whether the reference is relevant and worth investigating.

Here is a portion of the cited references from Google’s webpage for the ‘411 patent:

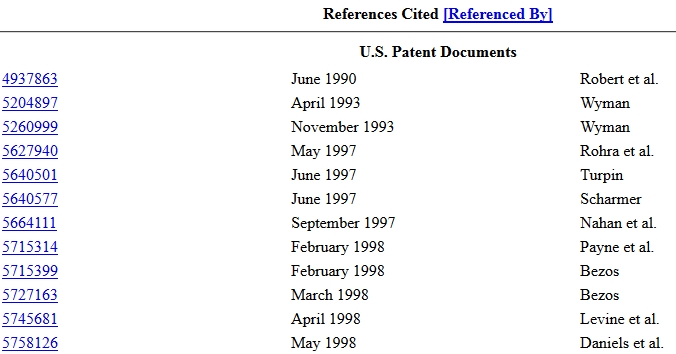

Here is a portion of the cited references from USPTO’s webpage for the ‘411 patent:

Not only can you find backward looking references cited, but you can also find forward looking references. Forward looking references are later patent documents that cite back to the patent, e.g. back to the ‘411 patent. A references is a forward looking reference in that it is a reference to a later patent document. The printed patent will not show forward looking reference because they are unknown at the time that the patent is granted. Forward looking references occur overtime as later patents cite back to an issued patent or a published patent application. The USPTO and Google provide forward looking citations, but presently FPO does not.

The forward looking references are accessible at the USPTO website by going to the patent’s webpage and clicking on the “[Referenced By]” link (shown in the screenshot above). The forward looking references are provided in the “REFERENCED BY” section of Google’s webpage for the ‘411 patent.

The backward looking references cited in the patent and the forward looking references that cite back to the patent document from later patent documents are important sources for finding other relevant patent documents.

5. Note the classes of the relevant patents

The USPTO has a subject matter classification system, where the USPTO classifies patents based on the subject matter of the patent. The classification system is an arrangement of hierarchical categories used to organize patents and patent applications by their characteristic. Therefore you can browse or search patent and published patent applications within a particular subject matter classification. The patent examiner specifies one and usually more than one class that the subject matter of the patent document pertains to.

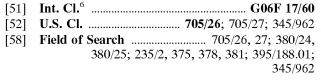

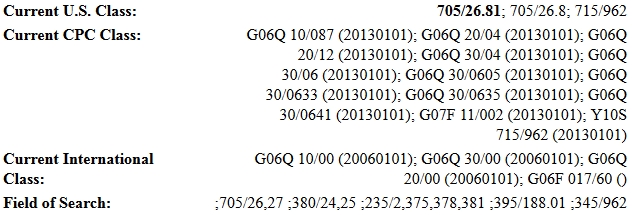

This is the classification section of the ‘411 patent:

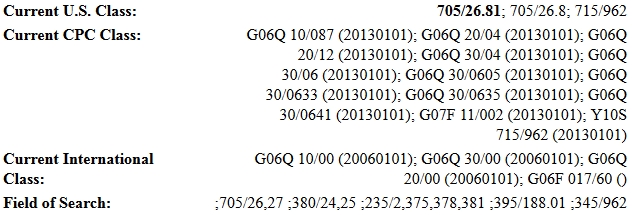

The international class is specified at G06F 17/60. G06F is the Electrical Digital Data Processing class. However, classes change over time, so at the time of this post the 17/60 subclass no longer exists. To find the current class that corresponds to the 17/60 class you can goto the USPTO webpage for the ‘411 patent. At the time of this writing, the USPTO webpage for the ‘411 patent shows the following current classifications:

The current international class for the ‘411 patent is G06Q 10/00.

There are at least three classification schemes (1) the US patent classification scheme, (2) the international patent classification scheme, and (3) the cooperative patent classification scheme.

The USPTO switched from using the US classification scheme to cooperative patent classification (CPC) scheme. In 2015, the USPTO stopped classifying patents in the US Classification system.

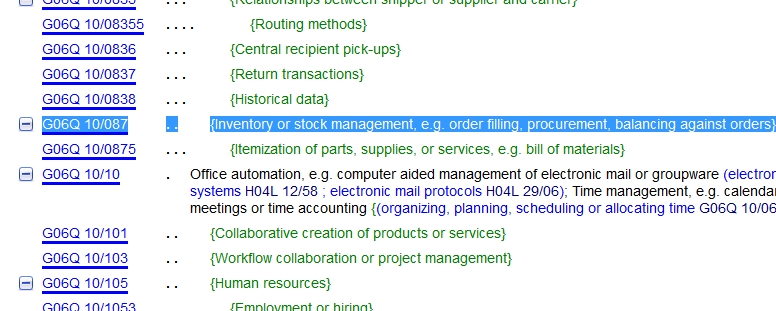

This post will focus on CPC based searching. The current CPC class of the ‘411 patent is G06Q (Data Processing Systems or Methods) and the subclass is 10/087 (Inventory or stock management, e.g. order filling, procurement, balancing against orders).

6. Review class definitions of noted classes

Beyond the primary class/subclass of G06Q 10/087 of the ‘411 patent, you should browse the class/subclass titles and definitions for each of the CPC classes listed. You can find the class/subclass titles and definitions at the Classification search page.

Not only does a one-click purchase involve “order filling” in subclass 10/087, but as noted above it may involve the following additional subclasses:

- G06Q 20/04 – Payment circuits

- G06Q 20/12 – Payment Architectures specially adapted for electronic shopping systems

- G06Q 30/04 – Billing or invoicing

- G06Q 30/06 – Buying, selling or leasing transactions

- G06Q 30/0633 – Buying, selling or leasing transactions, electronic shopping: lists, e.g. purchase orders, compilation or processing

- G06Q 30/0635 – Buying, selling or leasing transactions, electronic shopping: Processing of requisition or of purchase orders

- G06Q 30/0635 – Buying, selling or leasing transactions, electronic shopping: Shopping interfaces

- Y10 715/962 – Data processing: presentation processing of document, operator interface processing, and screen saver display processing: Operator interface for marketing or sales

Additionally the patent office considered relevant the class G07F 11/00 for “Coin-freed [payment activated] apparatus for dispensing, or the like, discrete articles:where the dispenser is part of a centrally controlled network of dispensers.” You might not immediately think of dispensing devices as relevant to a search for one-click online purchases, but they are related in that it is possible that a purchaser could receive a product with one action in both cases.

Class G07F 11/00 is an example of a class that you might not have thought of unless you reviewed the classes listed on relevant patents you find in your search.

You should make a list of relevant classes for classification searching. This list will be expanded and refined in steps 7 and 8 below.

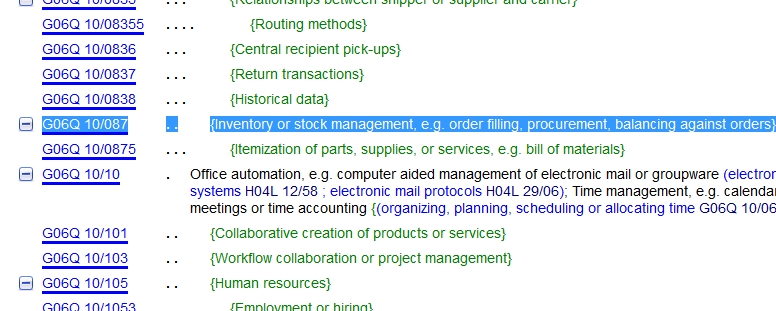

7. Review adjacent classes to the noted classes

Looking to the CPC schedule/scheme you can view the classes that are adjacent to those you have identified in the prior steps. It is possible that adjacent classes will be as relevant or more relevant than the classes you have already identified. This is an excerpt of the class scheme adjacent G06Q 10/087.

8. Search and browse CPC scheme for additional relevant classes

Next, to be sure that you find all the the potentially relevant classes you should keyword search the CPC Scheme and browse the CPC Scheme.

To search the CPC scheme, goto www.uspto.gov and enter keywords into the search box in the upper right corner. This is what the search box currently looks like:

Start each search with “CPC scheme” followed by your search terms, in this case “online purchasing.” The G06Q class is the first class in the result list, which matches the class G06Q that we found in the ‘411 patent. However, do not stop there, search with other keywords and combinations of keywords to find relevant classes.

Start each search with “CPC scheme” followed by your search terms, in this case “online purchasing.” The G06Q class is the first class in the result list, which matches the class G06Q that we found in the ‘411 patent. However, do not stop there, search with other keywords and combinations of keywords to find relevant classes.

9. Perform classification searches

Goto the patent search engines and search for patents and patent applications in the classes that you identified above.

At the USPTO you can search for all patents in class G06Q 10/087 by typing “cpc/G06Q10/087” on the advanced patent search page and all published patent applications in that class by performing the same search on the manual patent application search page. The search syntax is CPC/ followed by the class and subclass without any spaces.

Google Patents advanced search page provides a field for Cooperative Classification searching where you can enter the class/subclass without any spaces “G06Q10/087”. At the time of this writing, it does not appear that FPO has a field for searching the CPC.

10. Optionally narrow classification searches by keywords

At the time of this post, USPTO records show 5,046 patents in class G06Q10/087. In some cases, you may have to browse each and every one of those patents. In some cases, you may be able to refine your search by adding keywords to search within that class to the reduce result set. However, narrowing the search results by keyword runs into the keyword searching problem explained above.

11. Keep searching

One of the the hardest things about patent searching is knowing when you are done. Is it that no problematic patent document exists related to your invention or does it exist and you failed to find it?

There’s no universal answer to the question. Knowing whether a search is complete is usually a product of knowledge that you’ve covered all the relevant patent classes combined with knowledge borne by experience based knowledge of where you should be searching.

This post should give you a framework for patent searching. Then you can take those results to a patent professional for an opinion on how they impact your ability to obtain a patent.

The goal of a do-it-yourself patent search is to find patent documents that could present an obstacle to your effort to obtain a patent. If you do identify a potentially problematic patent document and a patent attorney confirms it is a substantial obstacle to obtaining a patent, you might save money by doing your own patent search.

However, as you can see above patent searching is not easy. The ability to perform a complete patent search is a product of experience, which there is no first-time DIY substitute for. Therefore, in the case you do not find any patent documents that are close to your invention, your next step is to have a professional patent search performed.

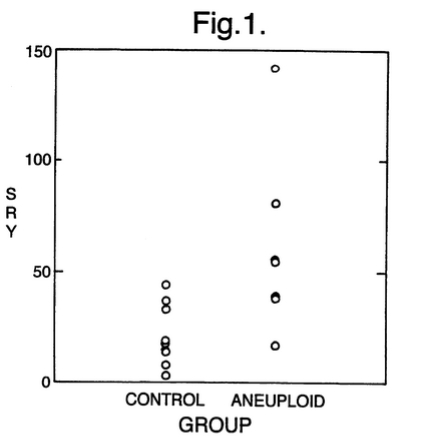

Today test results from a pregnant mother’s blood can detect characteristics of the fetus, such as genetic defects or gender. The method of detecting such characteristics was found non patent eligible by the Court of Appeals in Ariosa Diagnostics v. Sequenom, Inc., Nos. 2014-1139, 2014-1144 (Fed. Cir. 2015).

Today test results from a pregnant mother’s blood can detect characteristics of the fetus, such as genetic defects or gender. The method of detecting such characteristics was found non patent eligible by the Court of Appeals in Ariosa Diagnostics v. Sequenom, Inc., Nos. 2014-1139, 2014-1144 (Fed. Cir. 2015). The iPhone was released on June 29, 2007. Six days later on July 5, 2007, watch maker M.Z. Berger & Co. filed a trademark application on iWatch for watches, clocks, and related accessories. Coincidence?

The iPhone was released on June 29, 2007. Six days later on July 5, 2007, watch maker M.Z. Berger & Co. filed a trademark application on iWatch for watches, clocks, and related accessories. Coincidence? In 1997, Jeffery Sorensen founded a company and began selling rust preventive products under the trademark THE INHIBITOR. Sorensen claimed trademark rights in THE INHIBITOR mark and common law trademark rights in the Sorensen Crosshair provided on some of his products, shown to the right.

In 1997, Jeffery Sorensen founded a company and began selling rust preventive products under the trademark THE INHIBITOR. Sorensen claimed trademark rights in THE INHIBITOR mark and common law trademark rights in the Sorensen Crosshair provided on some of his products, shown to the right.

Can I patent this invention? One of the first steps in the patent process is to determine whether you can obtain a patent on the invention. The heavy lifting of this determination is a

Can I patent this invention? One of the first steps in the patent process is to determine whether you can obtain a patent on the invention. The heavy lifting of this determination is a

You search the trademark database at the USPTO and find that your competitor’s trademark registration was canceled because the competitor did not file

You search the trademark database at the USPTO and find that your competitor’s trademark registration was canceled because the competitor did not file  Kingsford-Clorox owned the trademark Duraflame for artificial firelogs. Kingsford-Clorox decided to get out of the firelog business and wanted to write off the goodwill associated with the Duraflame mark for accounting purposes. So it published a notice in the Wall Street Journal announcing the abandonment of the Duraflame trademark effective on the date of publication.

Kingsford-Clorox owned the trademark Duraflame for artificial firelogs. Kingsford-Clorox decided to get out of the firelog business and wanted to write off the goodwill associated with the Duraflame mark for accounting purposes. So it published a notice in the Wall Street Journal announcing the abandonment of the Duraflame trademark effective on the date of publication.