“[T]he lesson Edison drew from the experience was that invention should not be pursued as an exercise in technical cleverness, but should be shaped by commercial needs.”

Thomas Edison is an inventor famous for his long running electric light invention among many others. Edison accumulated over 1000 patents in his life time. His life and work is covered in Randall Stross’ book The Wizard of Menlo Park: How Tomas Alva Edison Invented the Modern World.

Thomas Edison is an inventor famous for his long running electric light invention among many others. Edison accumulated over 1000 patents in his life time. His life and work is covered in Randall Stross’ book The Wizard of Menlo Park: How Tomas Alva Edison Invented the Modern World.

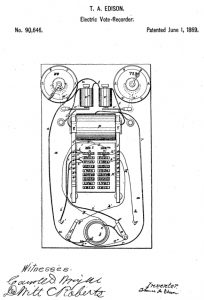

Early in his career, while working as a telegraph operator, Edition invented on the side. According to Stross, “Edison filed patent applications as fast as the ideas arrived.” The first patent application that Edison filed was for a legislative chamber vote recorder (U.S. Patent No. 90,646). The vote recorder could shorten the time it took to tabulate votes by hours.

The invention provided buttons at each member’s desk and the chamber’s speaker could see running totals for “aye” and “nay” on twin dials.

However, there was no interest in the Capital for the invention. Stross describes a Capital insider’s reaction to the invention as “undisguised horror.” Stross continues: “The minority faction would not embrace an expedited voting process because it eliminated the opportunity to lobby for votes, nor would the majority want a change, either.”

Stross concludes, “The vote recorder was a bust, and the lesson Edison drew from the experience was that invention should not be pursued as an exercise in technical cleverness, but should be shaped by commercial needs.”

Trademark rights are connected with actual use of a mark. Sometimes that use starts before an federal trademark is filed and sometimes it starts after a federal (

Trademark rights are connected with actual use of a mark. Sometimes that use starts before an federal trademark is filed and sometimes it starts after a federal ( Drafting a patent application often involves describing the invention both broadly and in detail. But how can something be described both broadly and specifically?A decision in a case between Sprint and Time Warner Cable illustrates one way.

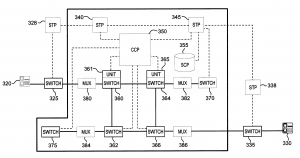

Drafting a patent application often involves describing the invention both broadly and in detail. But how can something be described both broadly and specifically?A decision in a case between Sprint and Time Warner Cable illustrates one way.

Devon Goocher applied to register MYCAH for music concerts, among other services. The USPTO refused registration based on a registration on MIKA for live performances by a musical entertainer in

Devon Goocher applied to register MYCAH for music concerts, among other services. The USPTO refused registration based on a registration on MIKA for live performances by a musical entertainer in