Previously I reported on the CSIRO v. Buffalo Technology case. There, the district court found CSIRO’s patent (No. 5,487,069) covered all 802.11a/g wireless technology and granted a permanent injunction against a wireless LAN vendor. CSIRO does not practice its patents, but instead seeks licenses from third parties. The court’s irreparable harm analysis is particularly interesting in light of CSIRO’s non-practicing status.

In eBay v. MercExchange, the Supreme Court provided that to obtain an injunction a patent holder must show (1) irreparable harm in the absence of an injunction; (2) inadequacy of money damages; (3) balance of hardship favors an injunction; and (4) the public interest would not be harmed by the injunction.

The irreparable harm portion of the analysis is generally where courts consider whether the plaintiff and the defendant are competitors or whether the plaintiff only licenses their patent rights to third parties.

Factor: Plaintiff’s Use of Additional Licensing Revenue to Solve Important Societal Problems

When a court issues an injunction, the plaintiff is able to obtain greater licensing fees due to the increased bargaining power that the injunction provides. The court emphasized the importance of the projects CSIRO would undertake with additional licensing revenue. The court found CSIRO used its licensing revenue to fund frontier projects. Those projects covered “areas of important research” including “addressing the increasing rate of obesity and the consequential increase of Type 2 diabetes, developing biomaterials that can be used to aid recovery from traumatic damage to the body, and examining the impact of climate change and mitigating its causes.” The court found this, among other things, supported a finding of irreparable harm.

What are the implications of this analysis? CSIRO is a Australian scientific research organization similar to the United States’ National Science Foundation. Can for-profit entities succeed in similarly arguing that they too would use increased licensing revenue to solve important societal problems? Will drug companies benefit from arguing their licensing revenues are to fund further research on particular life saving drugs? What about engineering firms and environmentally friendly products or defense contractors and counter-terrorism inventions? This particular aspect will not be determinative in the injunction analysis, but its interesting that the particular use of additional licensing revenue is a factor.

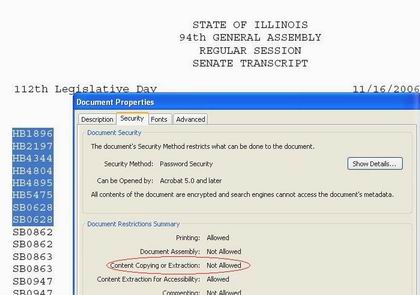

Scanned text-searchable transcripts of the Illinois House and Senate floor debates going back to 1971 are now available on the

Scanned text-searchable transcripts of the Illinois House and Senate floor debates going back to 1971 are now available on the