“Do you want to build your online brand on the sand of someone else’s domain registration or on a bedrock of a domain registered in your name?”

If you buy a piece of land, a house, or a building, would you allow the title to that property to name your real estate agent or your maintenance contractor? No, you would not. When you are spending hundreds of thousands of dollars or more on something you make sure that you actually own it in your name.

If you buy a piece of land, a house, or a building, would you allow the title to that property to name your real estate agent or your maintenance contractor? No, you would not. When you are spending hundreds of thousands of dollars or more on something you make sure that you actually own it in your name.

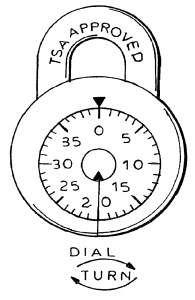

The same should be true when you buy a domain name for your website, regardless of the price. You should own and register it in your name, and not your technology provider’s name or anyone else’s name. When this is not the case, it can lead to a lot of problems and possibly tens of thousands of dollars in attorney fees to get your domain name back, as the following case appears to demonstrate.

We Merely Permitted You to Use Your Domain Name for 20 Years as a “Courtesy”Â

The First Liberty National Bank of Liberty Texas sued its technology service provider Memran Inc. (d/b/a Computer Solutions) and the service provider’s founder alleging that after First Liberty informed Memran that First Liberty was going to use another company for its technology needs and stop using Memran, Memran allegedly: “claimed for the first time to own the [First Liberty’s] FLNB.com domain name.” Memran also allegedly “claimed that it had merely ‘permitted’ First Liberty to use the domain name for nearly 20 years as a mere ‘courtesy’ to First Liberty, because it ‘[was] a Computer Solutions client.’ ”

We Own It and Will Shut It Down, But Want to Negotiate Getting it Back?

Then Memran allegedly “wrote that it ‘will no longer permit First Liberty’ to use the FLNB.com domain name after the parties’ business relationship concludes on February 1, 2018.” Memran then allegedly “immediately proceeded to say that it was ‘open to negotiations regarding transferring [the] flnb.com domain name” to First Liberty.'”

While this allegation does not directly say “buy/sell” its arguably implied that some compensation was sought. What compensation is sought? Maybe: I own it, but I’ll sell it to you for a fee (probably a large fee). Or maybe:Â we will transfer it to you if you continue to use us for your technology needs.

The complaint alleges that “At some point in late 1996 or early 1997, First Liberty instructed Computer Solutions, in its role as the bank’s information-technology provider, to register the internet domain name FLNB.com for First Liberty’s future use.” The complaint further alleges that:

“In its role as First Liberty’s information-technology provider, Computer Solutions listed its principal Meche as the registrant of the FLNB.com domain name. First Liberty allowed this because it trusted Computer Solutions and Meche to act in the bank’s best interest as the bank’s trusted information technology provider.”

Register It In Your Name

This was the first mistake. Its my opinion that you should not allow your technology provider to register your domain name in the technology provider’s name. True, maybe many/most times it will not be an issue because you have a good level of trust with the technology provider. However, you never know when things are going to go south.

If needed, have your technology provider come to your office and walk you through the steps of registering the domain name in your name. Make sure you are listed as the owner. Make sure you or a very trusted employee of your company is named as the contact. Further, make sure that if you are not the contact, that the contact email address is one where if email is sent to it, you are copied so you can be aware if someone tries to change ownership of the domain covertly.

Domain names probably have a higher chance of being registered in someone else’s name because many times, if the name is available, they can be obtain for a small fee on the order of tens of dollars. Transactions that involve low dollar amounts tend not to undergo a lot scrutiny. I don’t know the original cost of registering FLNB.com, but its likely that it was for a nominal amount. If First Liberty had spent 100K+ on the domain name FLNB.com, I suspect it would have been registered in First Liberty’s own name, in the same way real property (land and buildings) would be, because such transactions get more scrutiny and more process.

Yet, even if registering a domain name costs tens of dollars, you need to have it registered in your name. Having it registered in someone else’s name leaves you exposed to potential disputes about ownership later. Do you want to build your online brand on the sand of someone else’s domain registration or on a bedrock of a domain registered in your name?

Litigating a Cybersquatting Claim Is Expensive and Stressful; Making Sure the Domain Is in Your Name Is Cheap

From the Complaint it appears that First Liberty has a good chance of recovering the domain based on a claim of cybersquatting. But it had to file a complaint and an emergency motion for a temporary restraining order against the defendants over the holidays. It’s probably going to need a hearing on that motion plus more legal proceedings if the defendants fight back. First Liberty could be in for $10,000 in attorneys fees or more to get the domain back. Not cheap and very stressful over the holidays. What is cheap is making sure the domain is registered in your own name before there’s a problem, preferably at the beginning.

If its not currently registered in your name, have it transferred to you before there’s a problem.

While the domain name should be registered in your name, that does not mean that you can’t have a technology service provider do the work of developing and maintaining a website at the domain. You can have contractors build and maintenance a building without the contractor owning and controlling the land and building. We are talking about ownership and control here, not access.

The alleged facts naturally favor First Liberty at the complaint stage. Memran has not answered or responded yet to these allegations. So we don’t have Memran’s side of the story. Nevertheless, the allegations demonstrate the need of owning a domain name in your own name.

Case citation: The First Liberty National Bank, N.A., v. Memran, Inc., No. 1:17-cv-534 (E.D. Tx. Dec. 27, 2017)

The image at the beginning of this post is of First Liberty’s FLNB trademark in stylized form, which it has allegedly used since 1972. Trademark rights are the foundation of a cybersquatting claim.

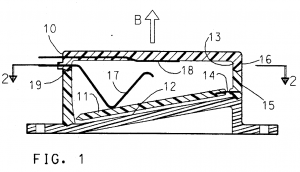

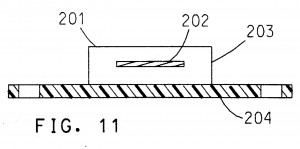

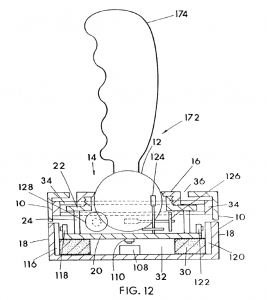

Anascape sued Nintendo alleging that Nintendo’s game controller infringed U.S. Patent 6,906,700Â (the ‘700 patent). Nintendo challenged the ‘700 patent asserting that it did not comply with the written description requirement of 35 USC 112.

Anascape sued Nintendo alleging that Nintendo’s game controller infringed U.S. Patent 6,906,700Â (the ‘700 patent). Nintendo challenged the ‘700 patent asserting that it did not comply with the written description requirement of 35 USC 112. Divided infringement occurs when no one party actually performs all of the steps of a patent claim. For example, one party performs some of the steps and another party performs the remaining steps. One way to solve this problem is to draft patent claims such that one party will likely perform all of the claimed steps.

Divided infringement occurs when no one party actually performs all of the steps of a patent claim. For example, one party performs some of the steps and another party performs the remaining steps. One way to solve this problem is to draft patent claims such that one party will likely perform all of the claimed steps. LNJ Vineyards LLC

LNJ Vineyards LLC

If you buy a piece of land, a house, or a building, would you allow the title to that property to name your real estate agent or your maintenance contractor? No, you would not. When you are spending hundreds of thousands of dollars or more on something you make sure that you actually own it in your name.

If you buy a piece of land, a house, or a building, would you allow the title to that property to name your real estate agent or your maintenance contractor? No, you would not. When you are spending hundreds of thousands of dollars or more on something you make sure that you actually own it in your name. GeoDynamics sued DynaEnergetics for trademark infringement of GeoDynamics’ REACTIVE trademark. GeoDynamics owned U.S. Trademark Registration No. 3,496,381 for the REACTIVE mark. After a bench trial the court found that REACTIVE was generic for the goods of fracturing charges for use in oil and gas wells and ordered the registration cancelled.

GeoDynamics sued DynaEnergetics for trademark infringement of GeoDynamics’ REACTIVE trademark. GeoDynamics owned U.S. Trademark Registration No. 3,496,381 for the REACTIVE mark. After a bench trial the court found that REACTIVE was generic for the goods of fracturing charges for use in oil and gas wells and ordered the registration cancelled. SATA GmbH sued Discount Auto Body and Paint Supply LLC for infringing its product design trademarks in the alleged sale of paint spray guns.Â

SATA GmbH sued Discount Auto Body and Paint Supply LLC for infringing its product design trademarks in the alleged sale of paint spray guns.

Conventus Orthopaedics applied to register two marks CAGE PH and PH CAGE for surgical implants. The Examining attorney refused registration on the basis that each mark was descriptive. The Examining attorney argued that PH was descriptive for proximal humerus (bone). The TTAB reversed finding that there was not enough evidence to show that PH was descriptive.

Conventus Orthopaedics applied to register two marks CAGE PH and PH CAGE for surgical implants. The Examining attorney refused registration on the basis that each mark was descriptive. The Examining attorney argued that PH was descriptive for proximal humerus (bone). The TTAB reversed finding that there was not enough evidence to show that PH was descriptive. Automotive Technologies International (ATI) sued numerous vehicle and parts manufacturers including BMW and Delphi Automotive Systems for infringing

Automotive Technologies International (ATI) sued numerous vehicle and parts manufacturers including BMW and Delphi Automotive Systems for infringing