Questions often arise about the risks of waiting. Waiting to get started, waiting to file a patent application, waiting to launch a product or service, etc. The risk is that someone else is independently working on the same problem or the same idea and beat you to the market or the patent office or both. What’s the chance of someone independently inventing in your space? It is impossible to know for a particular circumstance, but we do know that independent invention around the same time happens. According to In The Plex: How Google Thinks, Works, and Shapes Our Lives, Larry Page of Google was not the only person in 1996 to recognized that the link structure of the internet was the basis for a powerful way to find information on the web. The resulting algorithm based on link information allowed Google’s search results to be much better than other search engines at the time it was introduced. Two others were working on this idea, but Google was the first to make it to market.

Questions often arise about the risks of waiting. Waiting to get started, waiting to file a patent application, waiting to launch a product or service, etc. The risk is that someone else is independently working on the same problem or the same idea and beat you to the market or the patent office or both. What’s the chance of someone independently inventing in your space? It is impossible to know for a particular circumstance, but we do know that independent invention around the same time happens. According to In The Plex: How Google Thinks, Works, and Shapes Our Lives, Larry Page of Google was not the only person in 1996 to recognized that the link structure of the internet was the basis for a powerful way to find information on the web. The resulting algorithm based on link information allowed Google’s search results to be much better than other search engines at the time it was introduced. Two others were working on this idea, but Google was the first to make it to market.

Adjacent Possible and Independent Invention

As Steve Johnson noted in his book Where Good Ideas Come From sometimes when a scientist or inventor comes up with a new idea or invention, they learn that one or more others have independently come up with the same invention at about the same time period, such as within a year. Johnson notes that this is because the invention becomes “an adjacent possible” once founding or necessary elements or parts are created, discovered, or otherwise available.

To demonstrate the idea of the adjacent possible, Johnson notes that if Youtube was created 10 years earlier in 1995 it would have failed. This is because in 1995 most web users were on slow dial-up connections and it could take an hour to download a standard Youtube clip. In 1995, Youtube’s innovation was not within the adjacent possible, but ten years later, with broadband internet and Adobe’s Flash technology, it was.

PageRank

As In the Plex explains, Larry Page realized you can estimate the importance of a web page by considering the web pages that link to it. Page called his resulting algorithm based on linking “PageRank.” Page said, “In a way, how good you are is determined by who links to you and who you link to you determine how good you are…”Both the number of links and the quality of the links mattered. If a respected web page linked to a page, that link would be worth more than a link from a less well-known or respected website.

In addition to considering the number and nature of links, the anchor text used for the link is considered. Early search engines would provide results based on the content of a particular page. Therefore the results to a search for “newspaper” might not include the most relevant results, such as the New York Times website, if the New York Times did not say “I’m a newspaper” or otherwise use the word “newspaper” on its website. This caused search engine results to be poor and allowed the best result to be buried under relevant results. If a web page used the word “newspaper” to link to the the New York Times web site, then newspaper is the anchor text. And if enough and/or important websites link using that anchor text, then search results for “newspaper” would include the New York Times website. Page’s algorithm ranked each web page based on the incoming links, anchor text, and other factors. The resulting ranking of each page was used to determine which search results were returned for a particular web query, which vastly improved the relevance of search results as compared with other search engines at the time.

Others Independently Discovered Linked Based Ranking

Jon Kleinberg, a postdoctroal fellow at IBM’s research center, discovered that the link text, e.g. what a linking page said when linking to anther site and how many pages linked to a particular site, was useful in determining the relevance of a particular page. While having the same core idea, Kleinberg and Page each approached it differently. Kleinberg wanted to understand network behavior, Page wanted to build something that helped people in searching the web. Kleinberg said “all sorts of IBM vice presidents were trooping through Almaden to look at demos of this thing and trying to think about what they could do with it.” But they couldn’t figure out what to do with it.

Another person,Yanhong (Robin) Li, in 1996 saw the link between the ranking of scientific papers based on the number of other papers that cited them and ranking web pages in the same way. He came up with a search method that calculated relevance from both the frequency of links and the content of anchor text, which he called RankDex. Li described this to his bosses at Dow Jones, but they didn’t do anything with it. Li said, “I tried to convince them [Dow Jones] it was important, but their business had nothing to do with Internet search, so they didn’t care.”

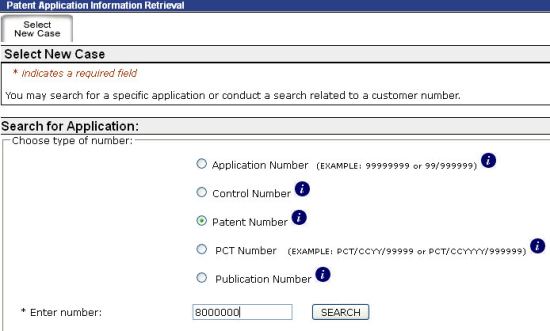

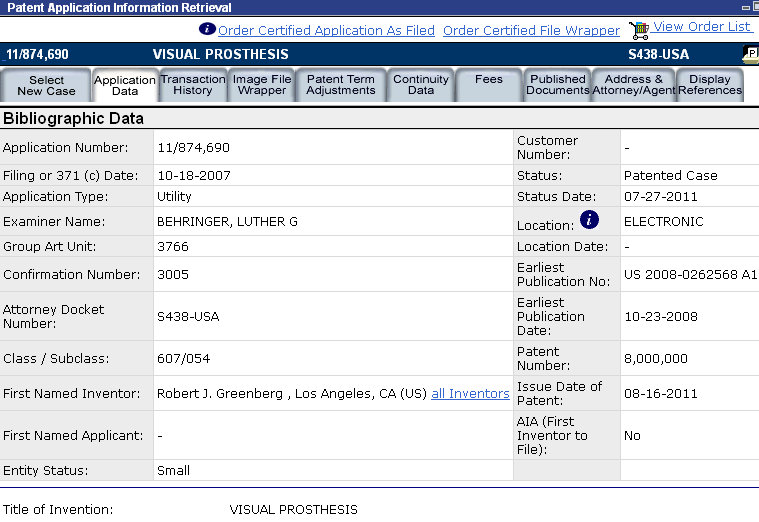

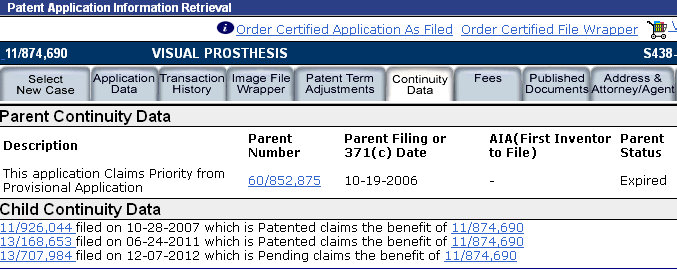

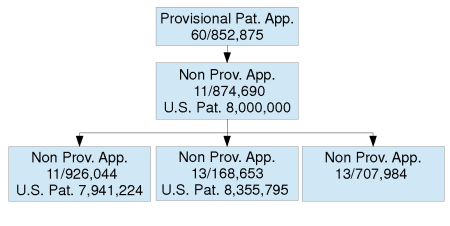

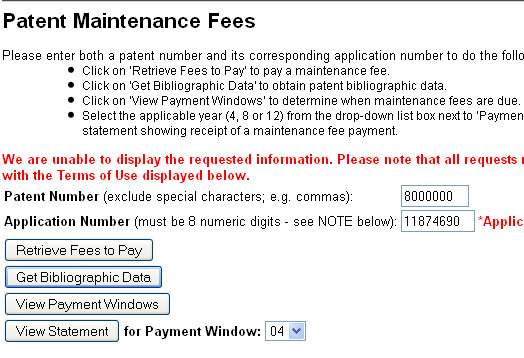

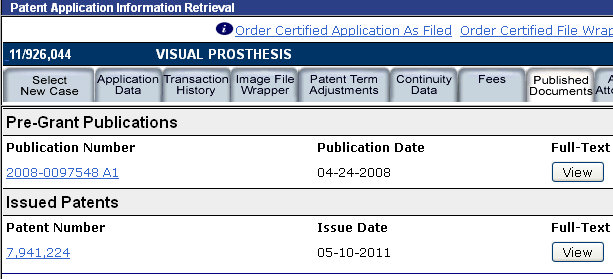

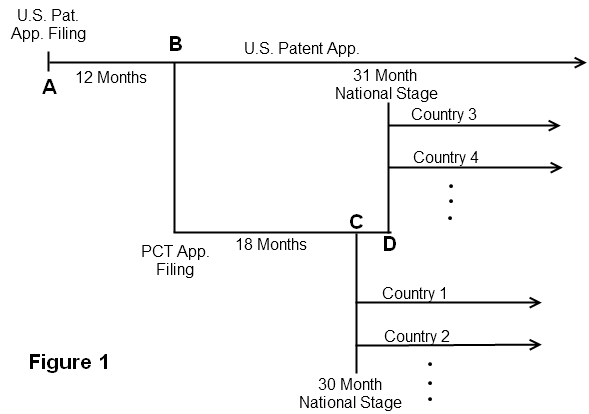

Li first filed a patent application himself in June 1996 after reading a self-help patent book. But then Dow Jones hired a patent attorney and filed another application on the same invention in February 1997, which resulted in US Patent No. 5,920,859. A patent application for Page’s Page Rank system was filed January 1997, which resulted in U.S. Patent 6,285,999. As you can see, the patent application were filed within about a month of each other. Li left Down Jones and eventually started Baidu in 2000, which is now the largest Chinese search engine.

Conclusion

These three individuals, Page, Kleinberg, and Li, were each independently working, without knowledge of the others, on one of the most important developments in improving internet search results, and in turn, improving the utility of the web. While it may be possible that you can sit on your ideas for years without consequence, waiting carries the risk that someone else is independently working on the same problem or invention as you. The patent office, and sometimes the market, rewards first movers.

Harley Davidson attempted to obtain a trademark registration

Harley Davidson attempted to obtain a trademark registration