How can a patent be granted over an invention and yet the commercialization (manufacture or sale) of the invention infringe a prior patent? A common misconception about a patent is the belief that a patent is a permission slip that allows you to make or sell your invention. But this is not the case. A patent is not a grant of permission for you to make your invention. Instead a patent provides a negative right. This means the patent allows you to stop others from making, using, selling, offering for sale, and importing your invention in the United States. Therefore in certain situations the commercialization of a patent invention can infringe a prior patent as explained below.

How can a patent be granted over an invention and yet the commercialization (manufacture or sale) of the invention infringe a prior patent? A common misconception about a patent is the belief that a patent is a permission slip that allows you to make or sell your invention. But this is not the case. A patent is not a grant of permission for you to make your invention. Instead a patent provides a negative right. This means the patent allows you to stop others from making, using, selling, offering for sale, and importing your invention in the United States. Therefore in certain situations the commercialization of a patent invention can infringe a prior patent as explained below.

Basic Example: The Wheel

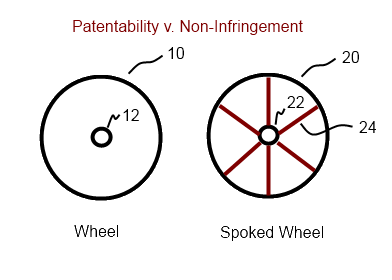

Here’s an example with a very basic invention to illustrate the concept. John invents the wheel. John files a patent application on the wheel and the patent claims “a circular surface 10 that orbits a hub 12.” The patent office grants John a patent because no one else had previously disclosed such a wheel in the prior art.

The Improvement: Spokes

Bob sees John’s wheel and decides to improve on it. Bob decides rather than having a solid wheel, which is how John’s wheel is made, Bob is going to take all the weight and material out of the wheel and connect the outer surface 20 to the hub 22 by a number of spokes 24. Bob applies for a patent on his spoked wheel. The Patent Office grants Bob a patent on his spoked wheel having a claim of: a circular surface that orbits a hub, where the circular surface is connected to the hub by a plurality of spokes. The patent office grants this patent because the prior art did not disclose a circular surface that is connected to the hub by a plurality of spokes. This is the new component. Since there is something sufficiently new in Bob’s invention, the Patent Office grants him a patent on it.

Infringement Analysis

Can Bob make his spoked wheel without infringing on John’s wheel patent? As explained above, a patent is not a grant of permission to create the corresponding product of the invention. So if John claims infringement, Bob can not win in defense by pointing to Bob’s patent. To determine whether Bob’s spoked wheel would infringe John’s wheel patent, we have to compare Bob’s spoked wheel to the claims of John’s wheel patent. As explained above John’s wheel patent claims “a circular surface 10 that orbits a hub 12.”

Does the spoked wheel have a circular surface that orbits a hub? Yes. The spoked wheel has a circular surface 20 that orbits a hub 22. A product infringes a patent if the product has each and every element of at least one claim of the patent (or an equivalent element, under the doctrine of equivalents, but that is outside the scope of our discussion here). It doesn’t matter that Bob’s spoked wheel has more elements than John’s patent claim, e.g. the spokes. Infringement is avoided in most cases by removing elements that are claimed, and not by adding elements that are not in the claims. The patent claim(s) set out the minimum that is necessary for a product/process to be covered by that claim. So John’s wheel patent may be avoided by removing the circular surface and making it square, for example, but that won’t function very well as a wheel. Further John’s wheel patent might be avoided by eliminating the hub, but then it would be difficult to connect the wheel to other things, e.g. wagons.

You can see that a patent having broad claims can cover variations of the invention that might not have been known at the time of the invention. The claim of John’s wheel patent does not say a circular surface that orbits a hub, where the area between the circular surface and the hub is solid or filled. Such a “solid” limitation would narrow John’s patent. The solid limitation would not cover Bob’s spoked wheel because the area between the circular surface and the hub is not solid, but instead is open with intervening spokes. However, John’s Patent claims were well drafted to not include too many unnecessary limitations. This also demonstrates how critically important claim drafting is in writing a patent application. Sometimes one word in the claim can make the difference between your patent covering another parties product or not.

In this example case, no one can make a spoked wheel since the commercialization of Bob spoked wheel would infringe John’s patent. Also, Bob has a patent on the spoked wheel so that John and others can’t make a spoked wheel. If a third party, Adam, started making a spoked wheel, Adam’s spoked wheel would infringe both Bob’s spoked wheel patent and John’s wheel patent. The only way that spoked wheels can be made and sold during the life of John’s patent, is if Bob and John come to a licensing agreement. Such a licensing agreement could provide that Bob will pay John a royalty on each spoked wheel sold until John’s patent expires. When John’s patent expires, then Bob can sell his spoked wheel without John interfering.

While this example provides that Bob invented an improvement to John’s wheel after seeing it, the results would be the same for the case where Bob invented the spoked wheel without seeing or knowing of John’s wheel.

Conclusion

As the above example shows, the Patent Office does not care if your invention would infringe a prior patent. They only ask whether the invention provides something that is sufficiently new. Therefore, your patent will not protect you from claims of infringement from others. A patent is an offensive weapon not generally defensive (except in certain strategies not relevant to this example). The only way to know whether your product will infringe a prior patent is to have a clearance or non-infringement search completed.