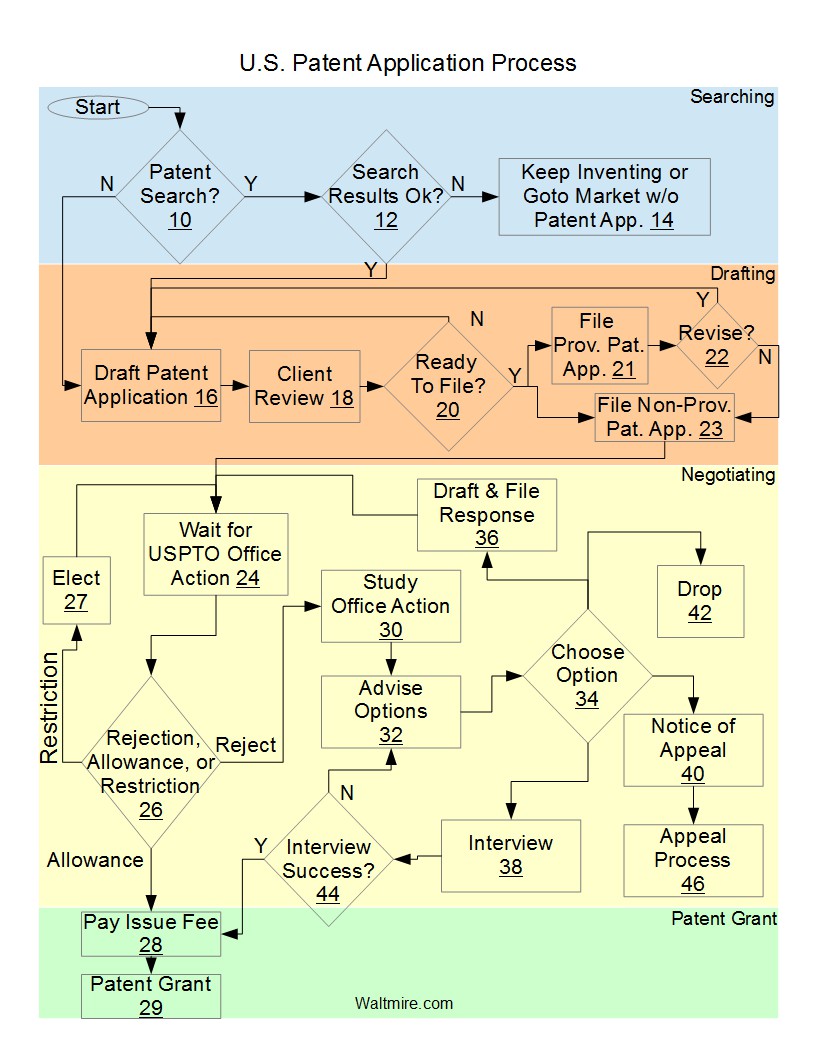

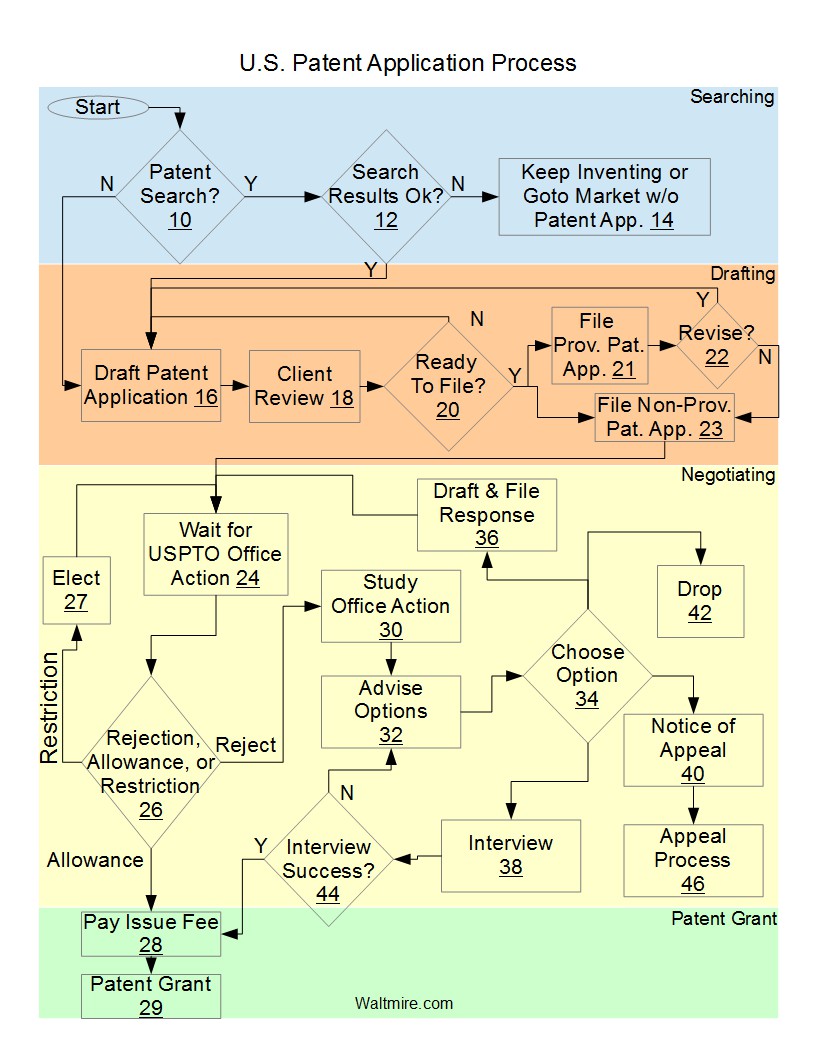

Seeking a patent is not a file it and forget it endeavor. Instead, it involves a process where work is likely required in multiple phases. The process of obtaining a utility patent in the US generally involves novelty searching, application drafting, waiting for the patent office to review the application, and negotiating with the patent office about the scope of patent protection. Each of those phases is shown in the U.S. Patent Application Process flow chart above, which I will describe in more detail below.

Patent Novelty Search

The first question is whether or not to have a patent novelty search performed. A patent novelty search is designed to tell you the likelihood of obtaining a patent on your invention. You are not required to have a search performed in order to file a patent application, but it is often recommended. Without a search, you my spend a lot of money filing an application only to find out from the patent office that your patent application is refused because your invention has already been disclosed in the prior art (so it is not new). Read more about patent novelty searching here.

If, at step 10, you decide to have a patent search performed, a search is performed by a patent attorney or patent searcher. To get the most benefit out of a patent search, it is best to receive an opinion from a patent attorney about the likelihood of obtaining a patent in view of the patent search results. After reviewing the search report and discussing it with your patent attorney, at step 12, you decide whether it is worth pursuing a patent application in light of the patent search results.

Sometimes the patent search results reveal a prior art reference that is identical to the invention and it is clear that a patent is not likely to be obtained on the invention. If so, the answer at step 12 is relatively easy, because there’s no option to pursue a patent application. In other cases, an identical result is not found in the patent search results, but one or more results are relatively close to the your invention. When one or more results are relatively close to your invention, the scope of a patent you might expect to obtain could be narrow. If the scope of protection you might obtain is narrow, then you must make a business decision whether pursuing such patent protection is likely to be valuable in light of the patent application expense you will occur in doing so.

If you decide not to pursue a patent, then at step 14, you can either (1) go to market without filing a patent application and compete in the marketplace or (2) decide it’s not worth pursuing this invention further in light of the prior art and focus your efforts on other inventions. This is a business decision. If you decide to proceed to market without a patent application, you might like to consider non-patent options for protecting your invention.

In other cases, the search results are favorable with no very close results.

Patent Application Drafting

If at step 12, the patent novelty search results are favorable, or if you otherwise decide proceed with filing an application, then you move to step 16 where the patent application is drafted. The patent attorney will take the information you’ve given him or her and draft the patent application. This drafting includes preparing or having prepared drawings as well as drafting the written description of the invention, among other parts of the application. The attorney may request additional information from you during the process of drafting the application.

When a first draft of the patent application is ready for review, at step 18, the draft application is sent to you for review. You then read the application carefully. If you don’t have any changes and the application is accurate, complete, and ready to file, then at step 22, the patent attorney files the patent application at the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).

If at step 20, you would like to provide comments, changes, or additions to the draft patent application, you provide those in writing or orally to the patent attorney. Then the patent attorney goes back to step 16 to draft and revise the patent application according to your feedback. Next, the newly revised patent application is sent to you for further review at step 18. Again you review the patent application and either approve it for filing or provide further comments, additions, changes, or other feedback. If the application is approved for filing, then the application is filed at step 23. Otherwise the feedback is taken by the patent attorney and incorporated into a further revised patent application. The review and revision process continues until you are happy with the patent application and approve it for filing.

First Provisional Patent Application or Non-Provisional Patent Application

If the patent application filed is a provisional patent application at step 21, then within one year a non-provisional patent application claiming the benefit of that provisional must be filed. If any content of the provisional needs be revised or added to, that can be done at step 22. However, any new subject matter added to the application will not get the benefit of the provisional filing date, because it was not in the provisional. Therefore, it is best to include all the subject matter in your earliest filing. However, sometimes new developments and inventions occur between the time the provisional is filed and the time for filing the non-provisional. If subject matter is to be revised or added to the content of the provisional before the non-provisional is filed, then the process goes back to step 16, 18, and 20 until the you are happy with the non-provisional application. Then at step 23 the non-provisional patent application is filed.

If the first application is a non-provisional, then you proceed directly to step 24 and wait for the patent office to review it.

As you can see, the USPTO does not substantively review provisional patent applications. A non-provisional must be filed for substantive review. Read more about choosing between first filing a provisional or a non provisional application here.

Negotiating (a.k.a Patent Prosecution)

Once the non-provisional patent application is filed (or design patent application), at step 24, you and your patent attorney wait for the USPTO to examine the patent application. Once received the results of USPTO’s examination are received, you enter the negotiation phase with the USPTO. Patent attorneys call this negotiation phase “patent prosecution.”

Restriction Requirement / Election

First an examiner at the USPTO will determine whether you tried to claim too many inventions in one patent application. If the Examiner believes you have, he or she will issue a restriction requirement. The restriction requirement can be issued in writing or by phone to your patent attorney. If USPTO did not issue restriction requirements, patent applicants could put multiple different inventions in one application. The restriction requirement practice is designed to ensures that the USPTO need only consider one invention per application.

If you receive a restriction requirement on your patent application, then at step 27, you’ll need to elect among the various inventions and claims groups designated by the patent examiner. At that time, you (through your patent attorney) can also object to the restriction requirement and argue that it is not a proper restriction requirement.

If the restriction requirement is not withdrawn or overturned following an objection by the applicant, or if the applicant chooses not to object, the examiner will examine only the elected invention and corresponding claims. In some cases, unelected inventions can be rejoined in the same application later in the negotiations. In other cases, you must file one or more divisional applications to cover those unelected inventions. The divisional application(s) are provided priority back to the filing date of the original application(s). Therefore, electing among the designated inventions does not mean that you will lose the unelected inventions, if those inventions are rejoined or pursued in divisional applications.

Substantive Examination

After the election or if no restriction requirement is made, the examiner will substantively examine the patent application to determine whether the claimed subject matter in the patent application is new in relation to the prior art and whether the other requirements for patenting are met. The USPTO will issue an “Office Action” explaining the results of their substantive examination.

Allowance

If the patent application is allowed on the first review by the patent office, then at step 26 a patent is very likely to be granted at step 29 if the issue fee is paid at step 28. This is known as first office action allowance. First office action allowance is not very common.

Also, the USPTO can withdraw allowance of application prior to a patent issuing, if they believe the allowance was a mistake. It is not common for an application to be withdrawn from allowance by the USPTO.

Rejection

A study of 20,000 patent applications in 2010 found that between 73% and 96% of the utility patent applications received a rejection on the first review by the USPTO (the first office action). Therefore, it is common for a patent application to be at least partially rejected upon first review. It is further common for a patent application to be allowed after one or more rounds of negotiation following the first rejection. Therefore, it is very common for patent applicants (through their patent attorney) to negotiate with the USPTO in order to obtain a granted patent. A first rejection is usually not the end of the road, it is the beginning of negotiations with the USPTO.

If the patent application is rejected in whole or in part, then at step 30, your patent attorney will review the content of the office action which explains the rejection(s). The patent attorney will also review the prior art references (e.g. prior public patents and patent applications) cited in the office action. The patent attorney will then assess the office action and provide the you with the your options at step 32 for responding.

As you can see in the diagram at step 34, there are at least four potential options after an office action rejection: drop the application at step 42, draft and file a written response at step 36, request an interview at step 38, or file an appeal at step 40.

1. Drop and Abandon Patent Application

Sometimes the client will decide to drop the application at step 42 in light of the office action. This may be due to the client’s decision, separate from the patenting process, that the invention no longer warrants pursuing patent protection. This may be due to the lack of commercial success of the invention or other business happenings related to the invention or the applicant.

In other cases, the prior art cited by the examiner may be such that the likelihood of obtaining a valuable patent is not high and the client does not want to spend further resources in an attempt to obtain a patent. This may happen in the case where a patent novelty search was not performed before filing the patent application.

In other cases, the prior art cited by the examiner may narrow the scope of the subject matter that could reasonably be protected by a resulting patent to the extent that such protectable subject matter is not commercially valuable enough to the client to continue pursue the patent application.

If you decide to drop the patent application, a response will not be filed to the office action. After the time period for response has expired the patent application will be abandoned and no patent will issue from it (unless properly revived based unintentional abandonment by petition).

2. File Written Response

If you decide to have a response drafted and filed, then at step 36 the patent attorney will prepare a written response to the office action. The patent attorney may amend the claims to avoid prior art, provide arguments why the examiner’s interpretation of the prior art or the examiner’s assertions are incorrect, provide a declaration from the inventor regarding aspects of the invention, and/or present other arguments or evidence related to the patentability of the claimed invention. The you may provide feedback regarding the written response to the office action. After the office action is filed, you will wait for a subsequent USPTO office action at step 24.

It is not unusual for the applicant to need to file responses to multiple office actions. Therefore, the applicant will may through steps 24, 26, 30, 32, 34, 36 and back to step 24 more than once (optionally including one or more rounds of interview at steps 34, 38, 44) .

In some cases, the applicant’s response to the first office action will overcome the prior art references cited by the examiner in the first office action. But the examiner has the option to search for additional prior art references to meet the claim limitations added in the first response. So as long as the applicant is making changes to the claims, the USPTO examiner has the opportunity to search and present new prior art references and arguments addressing those added or changed claim elements.

3. Interview with Patent Examiner

If you decide to proceed with an interview, the patent attorney will contact to the examiner at the USPTO and request an interview on a particular date and time agreeable between the examiner, patent attorney, and sometimes the patent applicant or inventor.

An interview provides the the patent attorney and the applicant/inventor the chance to orally discuss the patent application, the office action, the prior art cited in the office action, possible amendments to the claims to overcome the prior art, and other evidence relevant to the patentability of the invention defined in the claims. Sometimes the patent attorney will send proposed amendments to the patent examiner before the interview occurs. The interview can be held by phone conference or can be held in person at the USPTO’s offices.

At step 44, if the interview is a success, then the examiner will issue a notice of allowance allowing the patent application to grant into a patent. This process can take a number of forms. In some cases, the examiner will be convinced by the applicant’s argument regarding the allowability of the claims without further amendment. In other cases, the examiner and the applicant may come to an agreement about modifications to the claims or other actions that would result in an allowance of the application. Sometimes the examiner will put through those amendments directly by way of an examiner’s amendment. Other times the applicant will need to file a written response making the amendments that were agreed to lead to allowance.

In other cases, there is no agreement resulting from the interview, but often the applicant’s attorney learns information from the interview that will help prepare a response or decide whether it is time to appeal. If the interview does not result in an agreement for allowance, then the patent attorney proceeds to step 32 to advise the client about the options in light of the interview. Then at step 34 the client can choose among the options. It is unusual for another interview to immediately follow a prior interview. So after an interview, the options typically are to prepare and file a written response, drop the application, or pursue an appeal.

4. Appeal

Generally, when it appears that no further amendment or argument with the examiner is likely to result in an allowance of claims acceptable to the client, it may be an appropriate time to pursue an appeal. The appeal process is started by filing a notice of appeal at step 40. Then the appeal process proceeds at step 46. A discussion of the appeal process will be provided in a separate post. Obviously, an appeal can result allowance of the patent application, which would then proceed to step 28, although not shown in the flow chart above.

Allowance of Application and Patent Grant

When the USPTO is willing to allow the patent application to issue as a patent, either at step 26 or following a successful interview at step 44, the USPTO will issue a notice of allowance. The notice will indicate the application is allowed and will require the applicant to pay a government issue fee a set time period (usually within three months) of the date of the notice of allowance. At step 28, the issue fee is paid by the applicant (or the applicant’s attorney on behalf of the applicant). Shortly thereafter a patent is granted at step 29. After a utility patent is granted, maintenance fees must be paid at predefined intervals to keep it alive.

While each patent application is different, the flow chart and description above provide a summary of the various steps and decisions that might arise in pursuing a patent application in the US.

Co-author and publisher, Sugar Busters LLC, purchased the registered service mark SUGARBUSTERS (

Co-author and publisher, Sugar Busters LLC, purchased the registered service mark SUGARBUSTERS (