The problem with a provisional application is that it enables applicants to file patent applications that do not adequately describe the invention.

The USPTO does not examine or look at the content of the provisional application. So as long as you send a properly completed provisional coversheet, a document that purports to describe your invention, and pay the filing fee, the USPTO will probably not object to it. Whether your application described the invention in great detail or whether it is a “back of the napkin” submission, the USPTO will probably treat it the same. You will receive an official filing receipt and think you are protected.

But the difference between an adequate description and a back-of-the-napkin description may be the the difference between having a chance to obtain a valid patent and having no chance. It is the content of the application that matters regardless of whether you have a official filing receipt. And the USPTO will probably not tell you that you have not adequately described your invention when filing a provisional application. Instead, there is a fair chance that you will not find that out until it is too late to fix.

Example

For an example, let’s look at the case of New Railhead Mfg., LLC v. Vermeer Mfg. Co., 298 F. 3d 1290 (Fed. Cir. 2002). This is not a case of a back-of-the-napkin type provisional submission, but is it a case where the provisional application failed to adequately describe the invention claimed in the patent. As a result, New Railhead’s patent was invalid. Therefore, it is helpful in illustrating the potential problem with provisional patent applications.

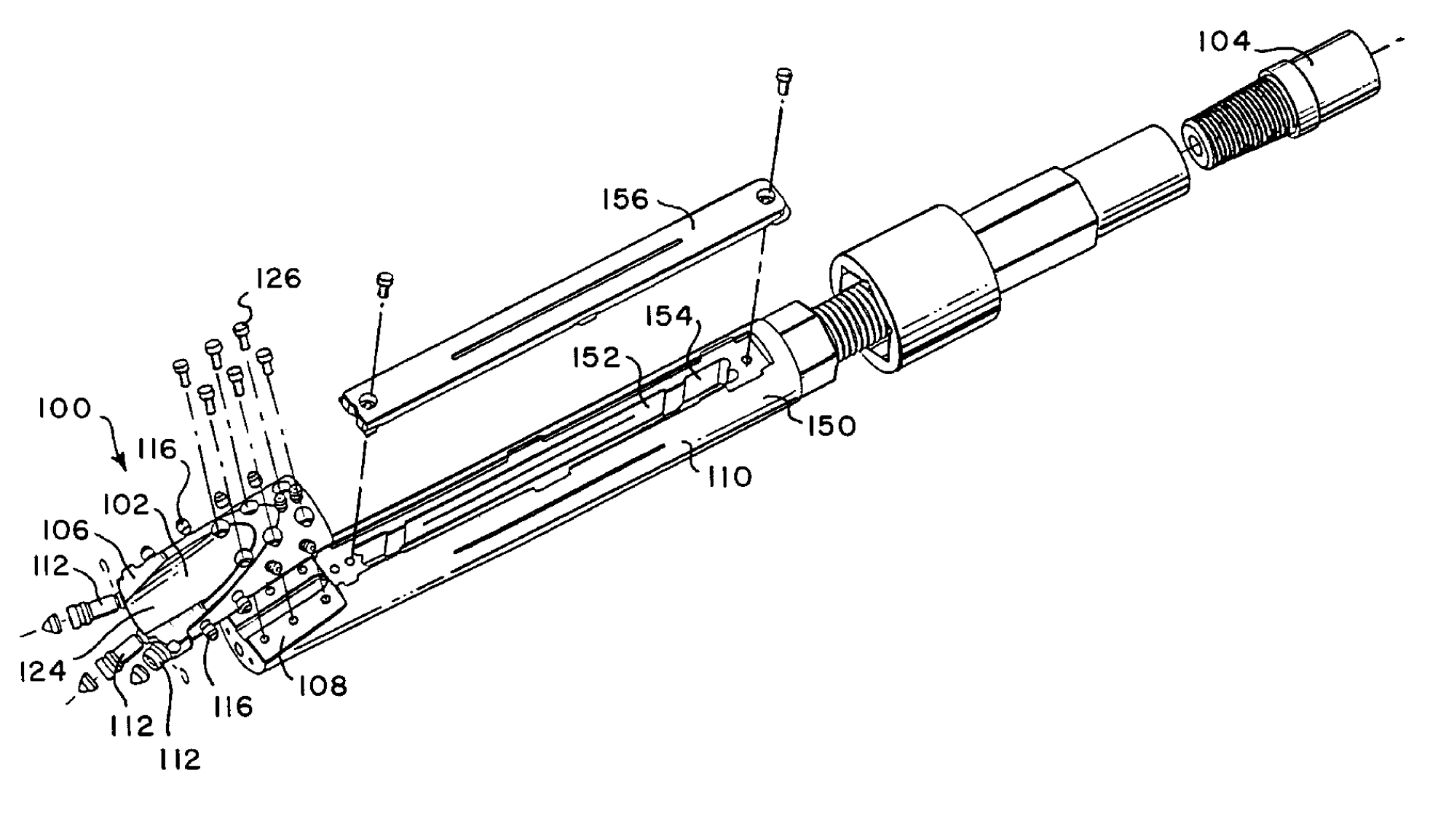

New Railhead Manufacturing sued Vermeer Manufacturing Company for infringing US Patent 5,899,283 (the ‘283 patent) on a drill bit for horizontal drilling in rock. The application that became the ‘283 patent claimed priority to a provisional application.

Here is a copy of Railhead’s provisional patent application. What you’ll notice is that it is missing some sections you would normally see in a non-provisional application, such as the brief description of the drawings, the summary of the invention, and claims. Also, if you compare the provisional application to the issued ‘283 patent, you’ll notice that the drawings of the provisional are not labeled with numbers to the extent that they are in the patent.

So the provisional lacked some of the sections and formalities that you would find in a non provisional and that you see in the issued ‘283 patent. But regardless of formalities, the question to consider is whether the provisional disclosed the invention claimed in the ‘283 patent.

Claim 1 of the ‘283 patent provides “the unitary bit body being angled with respect to the sonde housing.” The problem was the provisional application did not expressly describe the bit body as being angled with respect to the sonde housing. The court concluded this even though the provisional provided a “high included angle offsets for directional steering,” and enhanced performance that results from “multiplying the fracturing effect through leverage on the main drilling points.”

The court said “The passing references to a ‘high angle of attack’ and ‘high included angle offsets’ in the provisional, divorced from any discussion whatsoever of the bit-housing combination, do not convey to one of ordinary skill that [the inventor] was in possession of the bit-housing angle that is a limitation of the invention claimed in the ‘283 patent.”

Written Description Requirement

Railhead argued that one of ordinary skill would readily understand the angled bit body with respect to the sonde housing based on the totality of the provisional application. But this argument didn’t fly.

This is were a lot of inventors and engineers get tripped up. The court said, “It is not a question of whether one skilled in the art might be able to construct the patentee’s device from the teachings of the disclosure [but] whether the application necessarily discloses that particular device.” The written description requirement is stricter than what one skilled in the art would know. Therefore inventors and engineers may tend to leave out details that one skilled in the art would know, where it would be better to error on the side of caution and include those details.

When a patent attorney drafts an application the attorney often notices what appear to be gaps. When those gaps are brought to the attention of the inventor, it is not uncommon for the inventor to view the purported gap as something one skilled in the art would know. Nevertheless, to avoid a problem with the written description requirement, those gaps are often filled.

As If The Provisional Had Never Been Filed

Railhead admitted that it sold the patented drill bit more than one year before the filing date of the non-provisional application. The sale of a product more than one year before the filing of an application is prior art to that application. Therefore Railhead needed the benefit of the provisional application to avoid the patent being invalid over its own sale of the product. When Railhead could not rely on the provisional application filing date, the patent was found invalid. The end result was as if Railhead had never filed a provisional application at all.

SolutionÂ

The problem with a provisional application is that it enables applicants to file patent applications that do not adequately describe the invention. But, that problem can be solved by drafting a provisional application with substantially the same level of detail as you would draft a non-provisional application. When doing so there is nothing wrong with filing a provisional and it can protect the invention in the same manner as a non-provisional patent application. The bottom line is that the content of the application matters. And whether its a provisional or a non-provisional, the content of the application must adequately describe the invention.

Bearing or Avoiding Risks

One problem that individuals, startups, and small businesses face is they need to publicize the invention to obtain feedback to know whether it will be a commercial success. But patent law encourages you to file a patent application before you make your invention public. Do you spend money on having a patent application filed before you have commercial feedback on your invention? The answer with the safest patent position is yes. But the business ideal is to know the commercial prospects before investing substantial sums in the invention and its protection.

The provisional patent application is intended to address that problem by reducing the cost and reducing certain formalities required to file a provisional patent application. Therefore you can get something on file before going public. However, the patent application must still adequately describe the invention. And those cost and formality reducing features of the provisional application increase the risks that the provisional will not support claims in a later non-provisional application, as explained above.

There may be situations where the client has to decide how safe it/he/she wants to be from a patent prospective. There might be scenarios were lack of time or lack of money results in the client deciding to take on more risk. Maybe you didn’t think of filing a patent application until just prior to a public showing, a launch, or sales presentation to a customer. Maybe you don’t have the funds to pay a patent attorney to prepare a full patent application at the present time. Maybe you do not sufficiently know whether this invention commercially justifies the expense of preparing a full patent application.

In business, each owner and decision maker must decide what risks they are going to avoid and which they are willing to bear at any particular time. An attorney prepared patent application is ideal. And if you can’t or don’t want to hire an attorney to draft a full patent application at earliest time, then you are probably going to end up taking some risks.