This appears to be another case where the applicant pursued a hopeless claim. Why did this happen? The problem is that the applicant initially chose a weak trademark and then tried to prop it up by pursing a course that it could not win.

This appears to be another case where the applicant pursued a hopeless claim. Why did this happen? The problem is that the applicant initially chose a weak trademark and then tried to prop it up by pursing a course that it could not win.

Louisiana Fish Fry Products (LFFP) filed a trademark application on LOUISIANA FISH FRY PRODUCTS BRING THE TASTE OF LOUISIANA HOME! as shown at the beginning of this post.

The Trademark Examining Attorney and the Trademark Trial and Appeals Board (TTAB) both found that LFFP was required to disclaim “Fish Fry Products” as it was descriptive and generic of LFFP’s products. LFFP appealed this requirement to the Federal Circuit Appeals Court and lost in In Re: Louisiana Fish Fry Products, Ltd., No. 2013-1619, (Fed Cir. 2015).

The applicant could have avoided two rounds of appeal along with the associated attorney’s fees while still obtaining a registration on its mark. All it had to do was disclaim “Fish Fry Products.” But it didn’t, likely because of its prior dispute over Florida Fish Fry Products.

What is a Disclaimer?

A disclaimer is a statement made by a trademark applicant, usually at the request of the USPTO, to “disclaim an unregistrable component of a mark otherwise registrable.” 15 USC 1056. Or stated another way:

…a disclaimer of a component of a composite mark amounts merely to a statement that, in so far as that particular registration is concerned, no rights are being asserted in the disclaimed component standing alone, but rights are asserted in the composite; and the particular registration represents only such rights as flow from the use of the composite mark.

[Sprague Electric Co. v. Erie Resistor Corp., 101 USPQ 486, 486-87 (Comm’r Pats. 1954); TMEP 1213]

So here the question is does LFFP have rights in “Fish Fry Products” alone when used in relation to the applicant’s goods of: marinades sauce mixes, namely, barbecue shrimp sauce mix, remoulade dressing, cocktail sauce, seafood sauce, tartar sauce, gumbo filé, and cayenne pepper. The Trademark Examiner said no, the TTAB said no, and the Federal Circuit said no, and predictably so.

Why Fight? The History Against Florida Fish Fry Products

Is it so bad to disclaim a portion of text in a trademark at the request of the USPTO? The Trademark Act provides “No disclaimer…shall prejudice or affect the applicant’s or registrant’s rights then existing or thereafter arising in the disclaimed matter, or his right of registration on another application if the disclaimed matter be or shall have become distinctive of his goods or services.” 15 UCS 1056(b). Therefore, a disclaimer does not prohibit you from claiming rights in the disclaimed text later in ligation or in other trademark applications.

Why not just take the disclaimer in this case?

I speculate the reason is that in 2007 LFFP sued Charles Corry. Corry was selling products under the mark FLORIDA FISH FRY PRODUCTS. In 2008, Corry settled and agreed not to use Florida Fish Fry Products.

I predict LFFP would have had a very difficult time proving infringement by Corry if the case had not settled.

Here, LFFP probably didn’t want another Corry coming along and selling under Florida Fish Fry Products, Mississippi Fish Fry Products, Texas Fish Fry Products, or the like. So it was determined to fight this disclaimer requirement to better strengthen its position against such future problems on the common element “Fish Fry Products.”

The problem is LFFP didn’t have a chance. The fight over the disclaimer was a waste of money and a predictable loss.

Further, it not only was a loss of money, but the appeal put LFFP in a somewhat worse position than if it had not appealed. Â One concurring judge in this case asserted that FISH FRY PRODUCTS was generic. If FISH FRY PRODUCTS is generic, it can never achieve protection. Future defendants accused by LFFP could point to the this opinion that the term was generic as a defense.

The majority of the court did not reach the genericness question and instead relied on descriptiveness, as explained below.

Highly Descriptive: Fish Fry Products

The TTAB found that “Fish Fry Products” was highly descriptive of the applicant’s goods. The TTAB said that the evidence showed (1) public understands “fish fry†to refer to fried fish meals, (2) public understands “products†to mean, inter alia, “something produced; especially: COMMODITY … something . . . that is marketed or sold as a commodity,†(3) therefore the relevant public understands FISH FRY PRODUCTS to identify a type of sauce, marinade or spice used for fish fries.

No Acquired Distinctiveness

The applicant asserted that even if the mark was descriptive, the applicant had rights in “Fish Fry Products” through acquired distinctiveness (also known as “secondary meaning”). A trademark–or in this case the “Fish Fry Products” portion–has acquired distinctiveness when “in the minds of the public, the primary significance of a product feature or term is to identify the source of the product rather than the product itself.â€

Here, we ask this: when you see “Fish Fry Products” do you think of a source such as LFFP (then we have trademark protection) or do you think of the product itself (then no trademark protection)? Here, the “Fish Fry Products” refers to the product itself and not to the source, LFFP.

The applicant can show acquired distinctiveness by advertising expenditures, sales success, and length and exclusivity of use of the mark.

LFFP’s evidence fell short of proving acquired distinctiveness.

First, Under section 2(f) of the Lanham Act, the USPTO may accept five years of “substantially exclusive and continuous†use as prima facie evidence of acquired distinctiveness. But the USPTO is not required to do so. Therefore, LFFP’s allegation of five year of “substantially exclusive and continuous†of the mark did not prove acquired distinctiveness. The USPTO often does not accept section 2(f) declarations for highly descriptive marks.

Second, a declaration from LFFP’s president (1) stating that the LOUISIANA FISH FRY PRODUCTS has been used for 30 years was insufficient, and (2) providing sales and advertising expenditures for food products bearing LOUISIANA FISH FRY PRODUCTS was insufficient. This evidence was insufficient because it related to product bearing LOUISIANA FISH FRY PRODUCTS and not on the acquired distinctiveness FISH FRY PRODUCTS alone.

LFFP would have saved a lot of money, and an adverse ruling, by accepting the disclaimer and avoiding two rounds of appeal losses.

Co-author and publisher, Sugar Busters LLC, purchased the registered service mark SUGARBUSTERS (

Co-author and publisher, Sugar Busters LLC, purchased the registered service mark SUGARBUSTERS (

You need to know when to stop wasting money on trademark litigation. Here is a case where the plaintiff should have stopped on day two of the lawsuit, but didn’t.

You need to know when to stop wasting money on trademark litigation. Here is a case where the plaintiff should have stopped on day two of the lawsuit, but didn’t. The iPhone was released on June 29, 2007. Six days later on July 5, 2007, watch maker M.Z. Berger & Co. filed a trademark application on iWatch for watches, clocks, and related accessories. Coincidence?

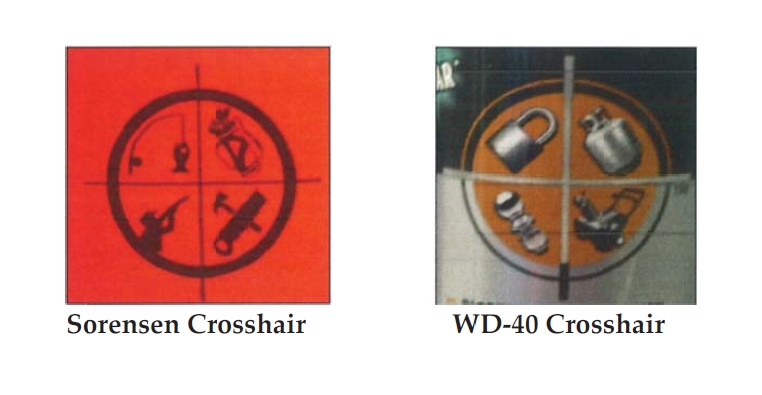

The iPhone was released on June 29, 2007. Six days later on July 5, 2007, watch maker M.Z. Berger & Co. filed a trademark application on iWatch for watches, clocks, and related accessories. Coincidence? In 1997, Jeffery Sorensen founded a company and began selling rust preventive products under the trademark THE INHIBITOR. Sorensen claimed trademark rights in THE INHIBITOR mark and common law trademark rights in the Sorensen Crosshair provided on some of his products, shown to the right.

In 1997, Jeffery Sorensen founded a company and began selling rust preventive products under the trademark THE INHIBITOR. Sorensen claimed trademark rights in THE INHIBITOR mark and common law trademark rights in the Sorensen Crosshair provided on some of his products, shown to the right.

You search the trademark database at the USPTO and find that your competitor’s trademark registration was canceled because the competitor did not file

You search the trademark database at the USPTO and find that your competitor’s trademark registration was canceled because the competitor did not file