“Mr. Morsa … admitted in the specification that the system as described in the patent ‘can be implemented by any programmer of ordinary skill . . . ‘ . . . Therefore, by using Mr. Morsa’s admissions, the Board simply held him to the statements he made in attempting to procure the patent.” – Federal Circuit Court of Appeals.

Properly drafting your own patent application can be difficult. Client-drafted DIY patent applications sometimes say too much, don’t say enough, or both. A client drafted patent application can say too little by failing to describe the invention with sufficient detail. And a client drafted patent application could say too much by making unnecessary admissions that can negatively impact the application.

Properly drafting your own patent application can be difficult. Client-drafted DIY patent applications sometimes say too much, don’t say enough, or both. A client drafted patent application can say too little by failing to describe the invention with sufficient detail. And a client drafted patent application could say too much by making unnecessary admissions that can negatively impact the application.

In the case of In Re Morsa, No. 2015-1107 (Fed. Cir. 2015), the applicant wrote his own patent application and in doing so made admissions that contributed to the final refusal of his patent application. This case demonstrates how admissions in the patent application can negatively impact the prospect obtaining a patent.

Morsa’s Application

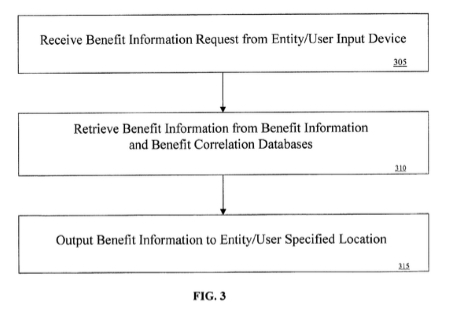

Morsa filed his patent application directed to a method and apparatus for furnishing benefits information. Claim 271 of his application provided:

A benefit information match mechanism comprising:

[1] storing a plurality of benefit registrations on at least one physical memory device;

[2] receiving via at least one data transmission device a benefit request from a benefit desiring seeker;

[3] resolving said benefit request against said benefit registrations to determine one or more matching said benefit registrations;

[4] automatically providing to at least one data receiving device benefit results for said benefit requesting seeker; wherein said match mechanism is operated at least in part via a computer compatible network.

The patent office cited a publication entitled Peter Martian Associates Press Release, dated September 27, 1999 (“PMA”) to show claim 271 was not new. Morsa argued that PMA did not provide enough detail to enable one skilled in this art to create Morsa’s claimed invention from the PMA without undue experimentation.

Prior Art

The Court maps disclosures from PMA to each of the elements of Morsa’s claim. The Court said with respect to each of the elements:

[1] [Regarding the first element] …the PMA reference describes the storage of “benefits and services that consumers receive from public and private agencies” along with the storage of “benefits services, health risks, or anything else an agency wishes to implement via its eligibility library.

[2] [The second element] correlates with the PMA’s statement that “consumers use the web to screen themselves for benefits, services, health risks, or anything else an agency wishes to implement via its eligibility library.”

[3] [The third element] maps onto the PMA’s use of the internet.

[4] [Regarding the fourth element] the PMA reference allows “consumers [to] use the Web to screen themselves for benefits, services, health risks, or anything else an agency wishes to implement via its eligibility library.”

Morsa’s Admissions in his Patent Application

Morsa argued that these high level statements in PMA did not provide enough detail to enable one create Morsa’s claimed invention. The Patent Office solved this problem be pointing to admissions in Morsa’s application (“the specification”) as to what one skilled in the art would have known at the time of the invention.

The court noted that Morsa’s specification admitted that:

- central processing units and memories were “well known to those skilled in the art,”

- central processing units and memories were “used in conventional ways to process requests for benefit information in accordance with stored instructions,”

- the system as described in the patent application “can be implemented by any programmer of ordinary skill in the art using commercially available development tools . . . ,” and

- “search routines for accomplishing this purpose are well within the knowledge of those of ordinary skill in the art.”

Therefore, based on those admissions, the Court concluded that one of ordinary skill in the art was capable of programming the invention based on the disclosure in the PMA reference.

In other words, the Court used Morsa’s admissions in the application to “fill in the gaps” in PMA as to what one skilled in the art would have know how to do related to Morsa’s invention.

Avoid Admissions in Application

If Morsa had not made such admissions, the Patent Office would have need to work harder to find reference that described the what one skilled in the art would have known at the time.

It probably would not have been too hard for the Patent Office to find a reference that described the use of databases and searching routines for use in an obviousness rejection. And, it possible that even if Morsa had not made the admissions in his application that his application still would have been refused.

Nonetheless, you do not what to make it easy for the patent office to refuse your patent application. Admitting that portions of an invention are “within the knowledge of those of ordinary skill in the art” or “well known to those skilled in the art” can be a problem, as shown in the Morsa case.

The reason Morsa made those admissions was so that he did not have to describe details of the items referenced as known, e.g. CPUs, search routines, etc. It’s a short cut.

But, it is better to describe the details of missing item or process or otherwise formulate statements without admitting components of the invention or the processes of making those components are “known by one skilled in the art.”

There maybe some instances where it would be acceptable to admit that a common component of the invention could be made by methods known by one skilled in the art. However, doing so is a double edge sword that can hurt you if not done properly. Given the potential downsides it is safer generally to avoid making such admissions.

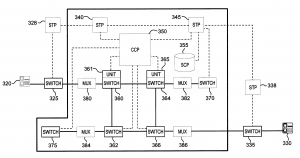

Drafting a patent application often involves describing the invention both broadly and in detail. But how can something be described both broadly and specifically?A decision in a case between Sprint and Time Warner Cable illustrates one way.

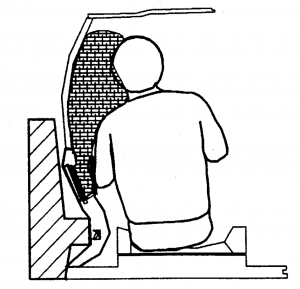

Drafting a patent application often involves describing the invention both broadly and in detail. But how can something be described both broadly and specifically?A decision in a case between Sprint and Time Warner Cable illustrates one way. Automotive Technologies International (ATI) sued numerous vehicle and parts manufacturers including BMW and Delphi Automotive Systems for infringing

Automotive Technologies International (ATI) sued numerous vehicle and parts manufacturers including BMW and Delphi Automotive Systems for infringing

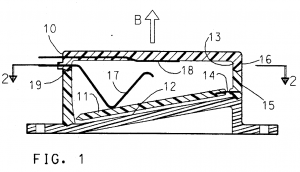

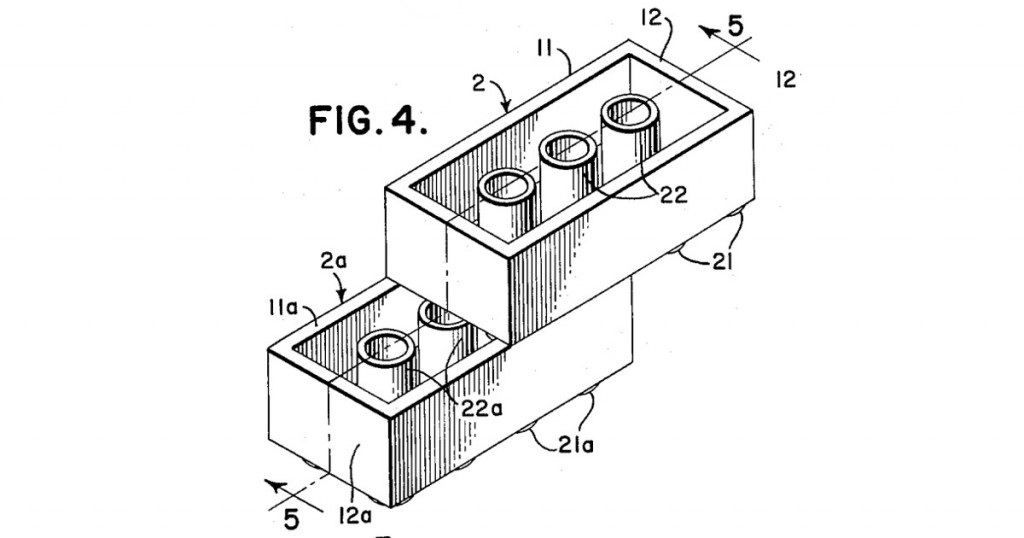

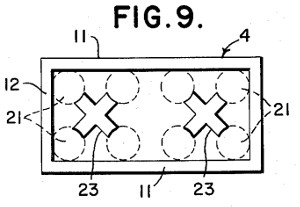

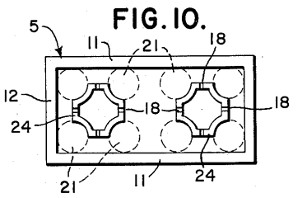

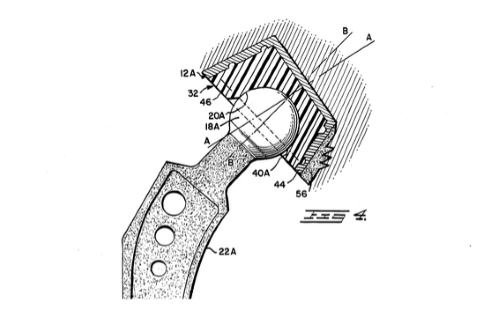

Â Figure 10 shows an alternative block having somewhat star-snapped projections 24.

Figure 10 shows an alternative block having somewhat star-snapped projections 24.

Properly drafting your own patent application can be difficult. Client-drafted DIY patent applications sometimes say

Properly drafting your own patent application can be difficult. Client-drafted DIY patent applications sometimes say  Clients often wonder why a patent application on a relatively simple invention is relatively long. The answer is that even the most simple inventions are not simple to describe properly in a patent application.

Clients often wonder why a patent application on a relatively simple invention is relatively long. The answer is that even the most simple inventions are not simple to describe properly in a patent application.