Kingsford-Clorox owned the trademark Duraflame for artificial firelogs. Kingsford-Clorox decided to get out of the firelog business and wanted to write off the goodwill associated with the Duraflame mark for accounting purposes. So it published a notice in the Wall Street Journal announcing the abandonment of the Duraflame trademark effective on the date of publication.

Kingsford-Clorox owned the trademark Duraflame for artificial firelogs. Kingsford-Clorox decided to get out of the firelog business and wanted to write off the goodwill associated with the Duraflame mark for accounting purposes. So it published a notice in the Wall Street Journal announcing the abandonment of the Duraflame trademark effective on the date of publication.

Two companies scrabbled to grab the Duraflame trademark, which resulted in the case of California Cedar Products Co. v. Pine Mountain Corp., 724 F.2d 827 (9th Cir. 1984). California Cedar won rights in the Duraflame mark because it was the first to use the Duraflame trademark after the mark was abandoned.

WindFall of Goodwill in Picking Up an Abandoned Trademark

When one company abandons a trademark, any other person or entity can grab the abandoned trademark through use or by filing an intent to use trademark application. The new person or entity picking up the trademark will receive a windfall of goodwill associated with that trademark.

Assuming the trademark is associated with a favorable reputation, the new trademark owner will gain that goodwill for essentially no cost, other than the cost of using the mark to make a sale or render service.

California Cedar acquired a windfall of goodwill associated with the Duraflame brand simply by being the first to use the mark after it was abandoned.

Problems in Reviving Abandoned Marks: You Don’t Know Its Abandoned

Why not go around grabbing up abandoned brands? You can, but the difficulty is knowing for certain that trademark is abandoned.

A trademark is abandoned if (1) its use in commerce has been discontinued (2) with no intent to resume use. The Lanham act provides “[n]onuse for 3 consecutive years shall be prima facie evidence of abandonment….” 15 U.S.C. § 1127. This means that after three years of nonuse there is a presumption that the mark has been abandoned. But, the trademark owner can rebut that presumption by presenting evidence that during the three years the owner formulated an intent to resume use of the trademark in commerce.

Determining whether the the trademark owner has an intent to resume using the mark is difficult. This is why it is possible, but often risky, to attempt to resurrect a trademark mark that appears to no longer be in use.

California Cedar Products Co. represents the easy case is where the trademark owner publicly announces the abandonment of the mark. However, this rarely happens.

It is more common for a company or entity to stop taking action publicly, e.g. stop selling in retail, stop updating a website, stop attending tradeshows, etc. These things may indicate that the company has stopped using the mark. But you can’t be sure. These things do not tell you (1) whether the company has in fact stopped selling, maybe the company is still using the mark to serve at least one customer, or (2) whether the the owner has an intent to resume using the mark if the owner has actually stopped using the mark.

Out of Business

Even when a company goes out of business or looks like it is out of business this is no guarantee that its trademarks are abandoned.

If the trademark owner goes out of business, it is possible that the trademark owner could transfer its assets, including the trademark, to another company. That receiving company would then have rights in the mark as long as the gap in trademark use is not too long.

Abandonment uncertainty is illustrated by the case of Specht v. Google, 758 F.Supp.2d 570 (N.D. Ill. 2010), aff’d, 747 F.3d 929 (7th Cir. 2014). As discussed in my prior post, Specht and his companies ADC and ADI abandoned the trademark rights in ANDRIOD DATA after ADI/ADC stopped using the Android Data mark in 2002 when ADI lost all of its customers and essentially went out of business. Google then picked up rights in ANDRIOD when it launched its mobile operating system in 2007.

Google’s rollout of ANDROID in 2007 was somewhat risky because at the time ADI owned a federal registration over the mark ANDROID DATA, and ADI/ADC maintained a website at androiddata.com. The website did not offer any price information about the Android Data software and was mostly purposeless. These uses were not enough to keep ADC/ADI’s trademark rights alive.

While Google was ultimately successful, Google did not know for sure that Specht and his companies had abandoned the ANDRIOD DATA trademark until Google obtained internal documents and information from Specht during the lawsuit.

Bankruptcy

If the trademark owner goes into bankruptcy, the trademark and associated goodwill can be sold off to satisfy debts of the owner. The entity receiving the trademark as a result of bankruptcy will then have rights in the mark as long as the gap in use of the mark was not too long.

Conclusion

You can gain a windfall of trademark goodwill by adopting an abandoned trademark. The problem is that it is usually difficult to determine whether the trademark is actually abandoned. A long passage of time may give an increased assurance of abandonment.

However, to be sure the mark is abandoned, it is best to have an express statement of abandonment, as happened with the Duraflame trademark. Yet, this rarely happens.

If an express statement of abandonment is not provided, then extensive due diligence is necessary to gain reasonable assurance of abandonment. As the abandonment standard considers the trademark owner’s intent to resume use of a trademark, reviving another’s trademark will likely carry some risk that abandonment has not occurred unless an express statement of abandonment is available.

While picking up an abandoned mark can provide a windfall to the new trademark owner, the uncertainty of abandonment is a risk that may offset some of the windfall benefit.

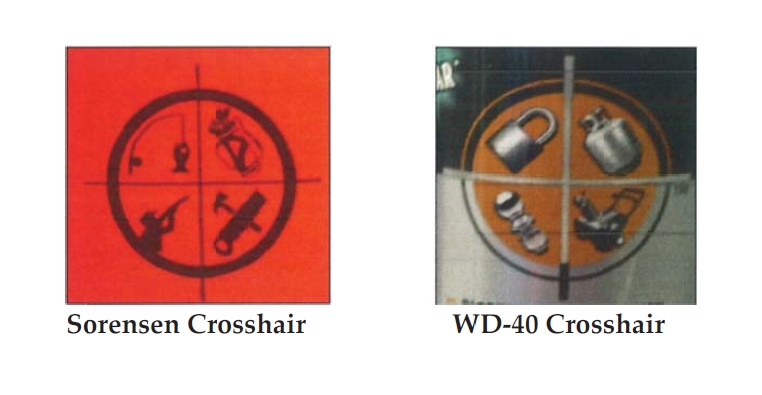

In 1997, Jeffery Sorensen founded a company and began selling rust preventive products under the trademark THE INHIBITOR. Sorensen claimed trademark rights in THE INHIBITOR mark and common law trademark rights in the Sorensen Crosshair provided on some of his products, shown to the right.

In 1997, Jeffery Sorensen founded a company and began selling rust preventive products under the trademark THE INHIBITOR. Sorensen claimed trademark rights in THE INHIBITOR mark and common law trademark rights in the Sorensen Crosshair provided on some of his products, shown to the right.

You search the trademark database at the USPTO and find that your competitor’s trademark registration was canceled because the competitor did not file

You search the trademark database at the USPTO and find that your competitor’s trademark registration was canceled because the competitor did not file  Kingsford-Clorox owned the trademark Duraflame for artificial firelogs. Kingsford-Clorox decided to get out of the firelog business and wanted to write off the goodwill associated with the Duraflame mark for accounting purposes. So it published a notice in the Wall Street Journal announcing the abandonment of the Duraflame trademark effective on the date of publication.

Kingsford-Clorox owned the trademark Duraflame for artificial firelogs. Kingsford-Clorox decided to get out of the firelog business and wanted to write off the goodwill associated with the Duraflame mark for accounting purposes. So it published a notice in the Wall Street Journal announcing the abandonment of the Duraflame trademark effective on the date of publication. In 1998, Erich Specht formed Android Data Corporation (ADC) and began selling e-commerce software under the trademark

In 1998, Erich Specht formed Android Data Corporation (ADC) and began selling e-commerce software under the trademark  Farzad and Lias Tabris were auto brokers. They operated websites at buy-a-lexus.com and buyorleaselexus.com connecting buyers with dealers selling Lexus vehicles.

Farzad and Lias Tabris were auto brokers. They operated websites at buy-a-lexus.com and buyorleaselexus.com connecting buyers with dealers selling Lexus vehicles. In

In  Spirits of New Merced (“Spirits”) applied to register the trademark YOSEMITE BEER for the sale of beer. But the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) refused to register the mark.

Spirits of New Merced (“Spirits”) applied to register the trademark YOSEMITE BEER for the sale of beer. But the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) refused to register the mark. British Bulldog Ltd. applied to register the trademark PLAYERS on the goods of men’s underwear. The trademark examiner  refused to register the mark claiming that it conflicted with a previously registered mark PLAYERS for the goods of shoes.

British Bulldog Ltd. applied to register the trademark PLAYERS on the goods of men’s underwear. The trademark examiner  refused to register the mark claiming that it conflicted with a previously registered mark PLAYERS for the goods of shoes.