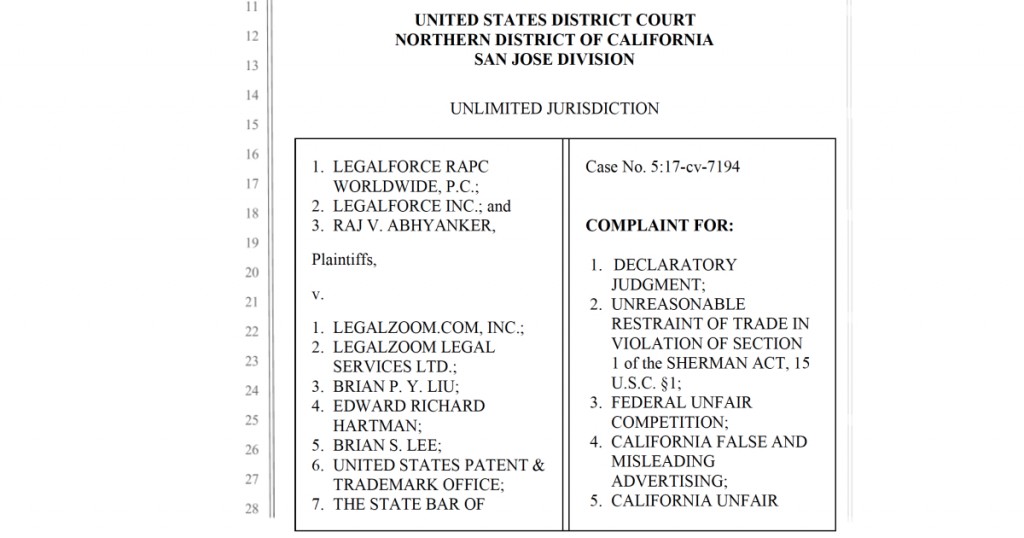

Raj Abhyanker is the owner of the lawfirm LegalForce RAPC Worldwide and of Tradmarkia.com. Raj and his lawfirm sued LegalZoom, the USPTO, and the State Bars of California, Arizona, and Texas based on what Raj alleged is LegalZoom’s unauthorized practice of law in connection with trademark application filing.

Alleged Unauthorized Practice of Law

Raj alleged that LegalZoom engaged in the unauthorized practice of law in connection with LegalZoom’s trademark application filing service. Raj and his law firm used LegalZoom to apply for two trademarks in connection with two of the Plaintiff’s businesses.

According to the complaint, LegalZoom represents on its website that it does not practice law. However, the complaint alleges that LegalZoom collects a service fee for its “peace of mind” review service. The complaint alleges that during the “class section and description modification step” LegalZoom routes customers to allegedly non-lawyer “Trademark Document Specialists.”

In the process of using LegalZoom to apply for two trademarks, the plaintiffs allege that LegalZoom provided legal advice by selecting a classification and modifying the goods and services description for a trademark application from the template thereby applying specific law to facts.

Why the Description (Identification) of Goods/Services is Important

Crafting a description of goods/services is an important step that can impact the scope of rights that exist under a trademark registration. This is because trademark rights are normally measured in relation to the goods/services on which the mark is used.

Drafting a description of goods/services is where many pro se applicants run into trouble. Sometimes drafting the description of goods can be relatively straight forward. But many times it is not.

Previously, I explained why the description of goods/service is important:

The description is important because it is what the USPTO will use to compare to other trademark registrations or trademark applications to determine whether there is a conflict. The comparisons occur in two types of situations.

The first comparison situation occurs when the USPTO reviews your application. There, the USPTO compares your mark to previously filed applications and registrations that are live. If the description is too broad, then the USPTO might find a conflict between your mark and a previous application or registration, which would not have occurred if your identification was not over broad…

The second comparison situation occurs when the USPTO is examining later filed trademark applications. If your description is too narrow then the USTPO might allow a later filed trademark application to be registered. But if your application had a proper description the USPTO would have blocked a later confusingly similar mark from being registered. Therefore, a description that is too narrow will not properly operate to block later filed trademark applications that would otherwise be in conflict. As a result, a narrow identification of goods and services will necessarily narrow the blocking effect of your application and narrow your trademark rights.

In addition, the description will be used by a court to determine the scope of rights that you have under trademark registration in a trademark lawsuit.

For a description to be crafted and used without any attorney involvement is problematic given the importance of the description.

Not surprisingly, according to the Complaint, Raj claims ethics attorneys advised him that he cannot have descriptions of goods/services prepared and used in trademark applications without attorney review, otherwise he would risk violating the unauthorized practice of law rules.

At the complaint stage, we don’t know LegalZoom’s process exactly. Nevertheless, preparing a description (identification) of goods/services for a trademark application is an important step that impacts the scope of the applicant’s trademark rights.

Citation: LegalForce RAPC Worldwide v. LegalZoom.com, Inc., no. 5:17-cv-7194 (N.D.Cal. 2017) [Complaint, Exhibits to Complaint].

If you buy a piece of land, a house, or a building, would you allow the title to that property to name your real estate agent or your maintenance contractor? No, you would not. When you are spending hundreds of thousands of dollars or more on something you make sure that you actually own it in your name.

If you buy a piece of land, a house, or a building, would you allow the title to that property to name your real estate agent or your maintenance contractor? No, you would not. When you are spending hundreds of thousands of dollars or more on something you make sure that you actually own it in your name. GeoDynamics sued DynaEnergetics for trademark infringement of GeoDynamics’ REACTIVE trademark. GeoDynamics owned U.S. Trademark Registration No. 3,496,381 for the REACTIVE mark. After a bench trial the court found that REACTIVE was generic for the goods of fracturing charges for use in oil and gas wells and ordered the registration cancelled.

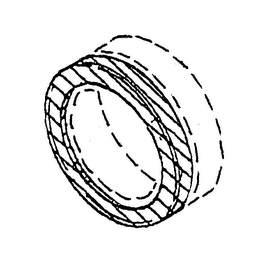

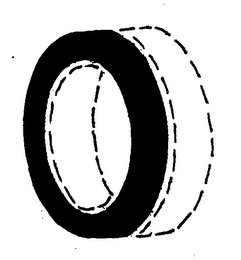

GeoDynamics sued DynaEnergetics for trademark infringement of GeoDynamics’ REACTIVE trademark. GeoDynamics owned U.S. Trademark Registration No. 3,496,381 for the REACTIVE mark. After a bench trial the court found that REACTIVE was generic for the goods of fracturing charges for use in oil and gas wells and ordered the registration cancelled. SATA GmbH sued Discount Auto Body and Paint Supply LLC for infringing its product design trademarks in the alleged sale of paint spray guns.Â

SATA GmbH sued Discount Auto Body and Paint Supply LLC for infringing its product design trademarks in the alleged sale of paint spray guns.

Conventus Orthopaedics applied to register two marks CAGE PH and PH CAGE for surgical implants. The Examining attorney refused registration on the basis that each mark was descriptive. The Examining attorney argued that PH was descriptive for proximal humerus (bone). The TTAB reversed finding that there was not enough evidence to show that PH was descriptive.

Conventus Orthopaedics applied to register two marks CAGE PH and PH CAGE for surgical implants. The Examining attorney refused registration on the basis that each mark was descriptive. The Examining attorney argued that PH was descriptive for proximal humerus (bone). The TTAB reversed finding that there was not enough evidence to show that PH was descriptive. Yesterday, I wrote about Contraband Sports LLC’s

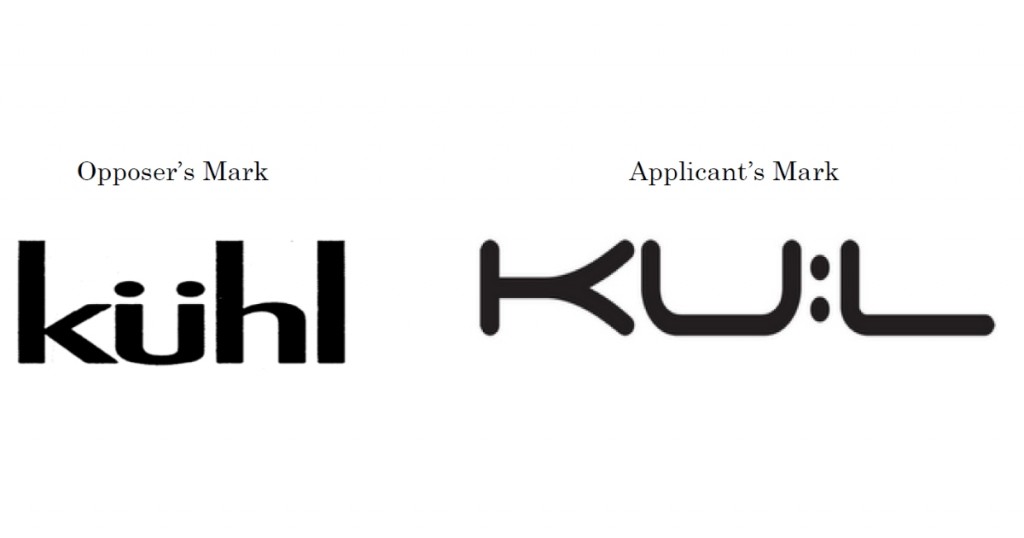

Yesterday, I wrote about Contraband Sports LLC’s

Mainstream Property Group, LLC applied to register the mark NEXT HOMES Â for providing assisted living facilities as well as for providing long-term care facilities and short term rehab facilities for seniors. NextHome, Inc. opposed the application based on its NEXTHOME mark, which was registered for real estate brokerage services.

Mainstream Property Group, LLC applied to register the mark NEXT HOMES Â for providing assisted living facilities as well as for providing long-term care facilities and short term rehab facilities for seniors. NextHome, Inc. opposed the application based on its NEXTHOME mark, which was registered for real estate brokerage services.