Update: The USPTO retired Public PAIR on August 1, 2022. The file history and status of a US patent or published patent application can be accessed via USPTO’s Patent Center at https://patentcenter.uspto.gov.

The USPTO provides online access to the file history and the current status of patents and published applications through a system called PAIR (Patent Application Information Retrieval). The file history, sometimes called the file wrapper, is a record of all the documents filed by the applicant and the USPTO regarding a patent or patent application. Review of the file history can be helpful in many circumstances to understand more about what the applicant said to the USPTO, during the prosecution of the application. You can also determine the status of a published application or patent using public PAIR.

The USPTO provides online access to the file history and the current status of patents and published applications through a system called PAIR (Patent Application Information Retrieval). The file history, sometimes called the file wrapper, is a record of all the documents filed by the applicant and the USPTO regarding a patent or patent application. Review of the file history can be helpful in many circumstances to understand more about what the applicant said to the USPTO, during the prosecution of the application. You can also determine the status of a published application or patent using public PAIR.

Here’s a navigation table to make it easier to skip to the sections that are of interest.

- Access and Logging in

- Bibliographic Data (Application/Patent Status)

- Transaction History

- Image File Wrapper (Downloadable Files)

- Continuity Data

- Maintenance Fees

- Published Documents

- Address & Attorney/Agent

- Display References

- Conclusion

1. Access and Logging In

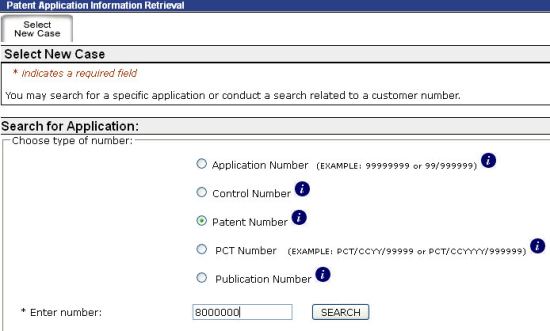

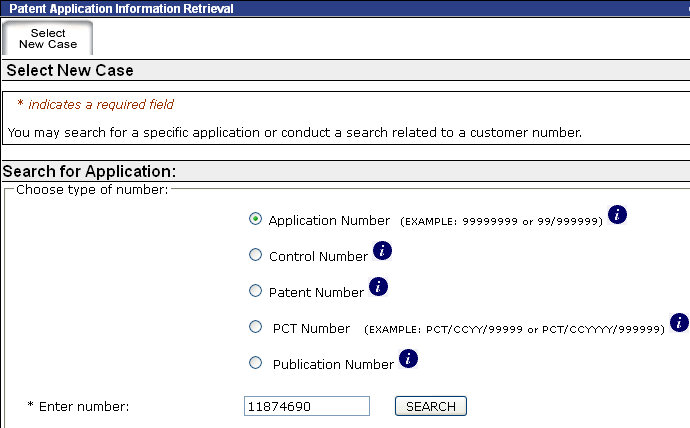

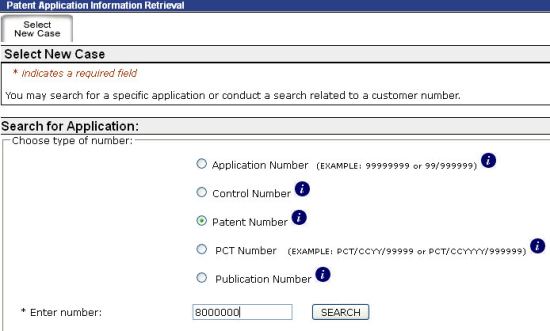

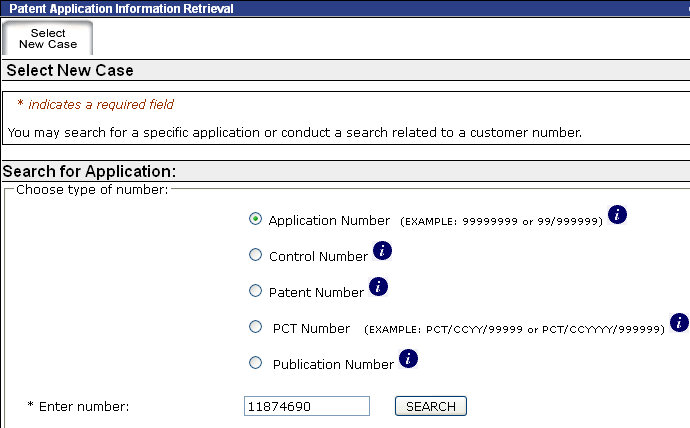

Currently you can access public PAIR by going to http://portal.uspto.gov/pair/PublicPair. Then you will be asked to enter text/characters at the CAPTHCHA stage. Next, you will see a page with a portion showing a tab “Select New Case”. There you have five options for the type of number you will enter in the search box: (1) the patent application number, (2) a control number, (3) the patent number, (4) a PCT number, (5) a publication number. Select the correct option for the number you will enter. Then enter the number in the search box and press the search button.

Patent Number. As an example, I selected the patent number option and entered 8,000,000 in the search box to retrieve the file history of U.S. Patent No. 8,000,000.

Patent Application Number. Alternatively, I could have selected application number and entered 11874690, which is the application number that corresponds to U.S. Patent No. 8,000,000. If you are looking up your own published patent application, you can select application number radio button and enter your application number. If your patent application has not yet published as an application, you will not be able to access it through public PAIR.

Back to the Top

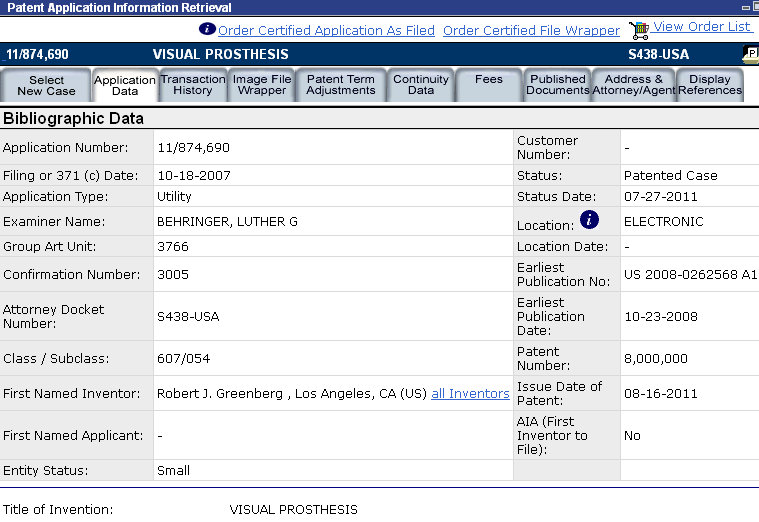

2. Bibliographic Data (Status)

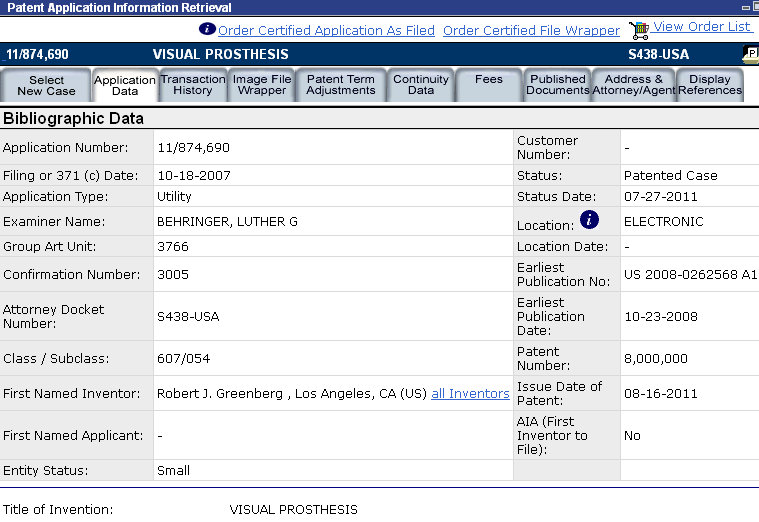

Next you are presented with the Bibliographic data under the application tab. Bibliographic data contains the application number, the filing date, the application type, the Examiner, the group art unit, the attorney docket number, the class and subclass of the application, the inventor’s name, the entity size, the status of the case, the date of the status update, the location, the application publication date, the application publication number, the patent number, the patent issue date, whether the application was/is subject to the America Invents Act, and at the bottom, the title of the invention.

Back to the Top

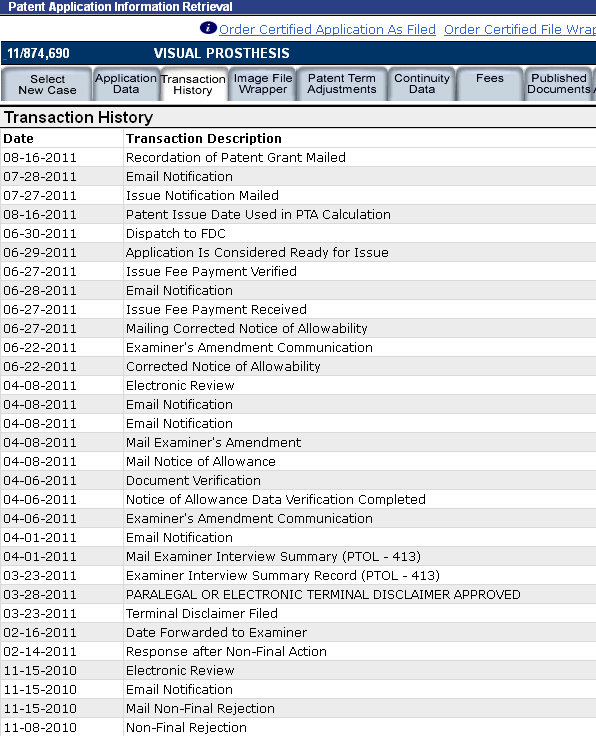

3. Transaction History

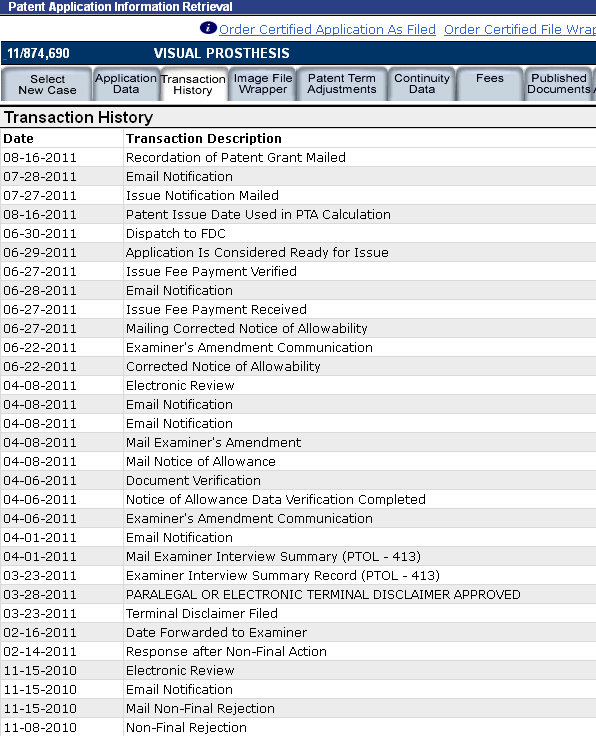

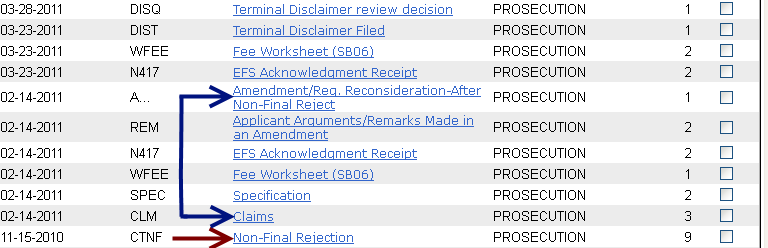

The transaction history tab shows all the transactions in the case, including items filed by the applicant, and process flows and happenings at the USPTO regarding the application. The transaction history does not provide any links to documents, those are found in the Image File Wrapper tab.

The Transaction history can show you internal happenings at the USPTO related to the case that do not show up as filed documents in the Image File Wrapper tab. For example, as shown below the applicant’s response, which is filed on 2-14-2011, was forward to the Examiner on 2-16-2011. However, this forwarding notation is not found in Image File Wrapper tab.

Back to the Top

4. Image File Wrapper

The USPTO started providing electronic file histories at the USPTO in 2003. If the patent application was filed before 2003, the file history might not be available online. In that case, you will need to goto the USPTO or hire a service, such as ReedTech, to goto the USPTO for you and copy the file history.

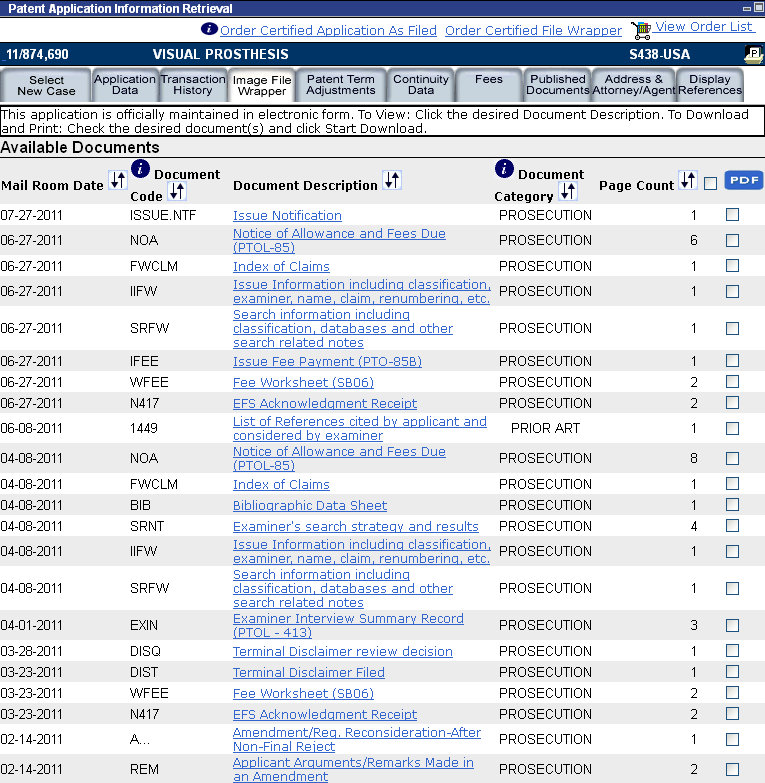

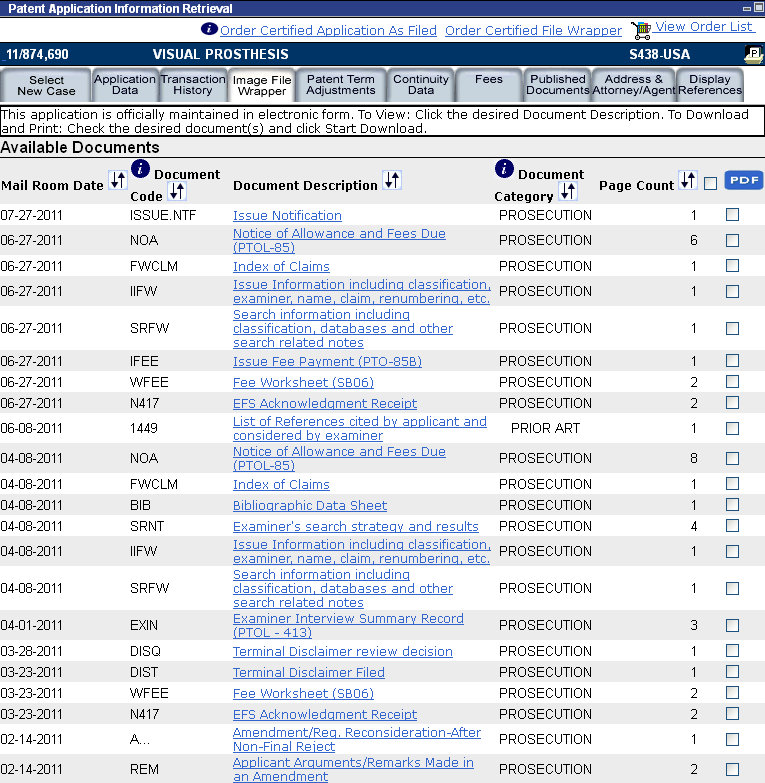

The image file wrapper tab shows all the documents filed by the applicant or issued by the USPTO in the case. The file wrapper tab also allows you to download the documents filed in the case in PDF format, by selecting the corresponding check-box and clicking the “PDF” icon at the top right.

Non-patent literature (NPL) is viable in the history but not downloadable via PAIR over copyright concerns, e.g. that easy access to these documents will facilitate copyright violations by the public and negatively impact the copyright holders ability to charge for these works. NPL are prior art documents filed by the applicant, such as journal articles, excerpts from books, or other publications. On the image file wrapper tab you can see (not shown above) the NPL in the case of US Patent 8,000,000 was filed on 1-08-2009 and the check box for selecting and downloading at the right is grayed-out.

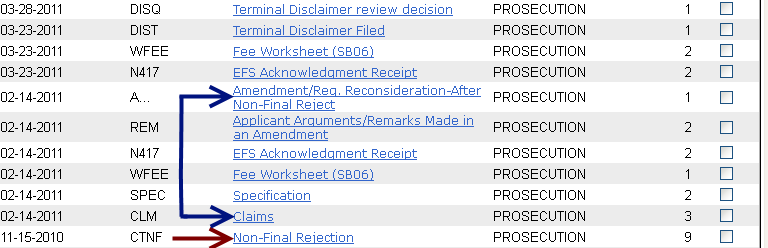

Looking at the image file wrapper for US Patent 8,000,000, we see that the USPTO issued a non-final rejection on 11-15-2010, which was the third rejection in the case (see the non-final rejection on 3-06-3009 and the final rejection on 7-17-2009). On 2-14-2011 the applicant filed a response presenting remarks having arguments for patentability, amendments to the specification, and amendments to the claims. The response on 2-14-2011 was successful in overcoming the Examiner’s refusal of 11-15-2010 because on 4-08-2011 the USPTO issued a Notice of Allowance (NOA), the applicant paid the patent issue fee on 6-27-2011 and the patent was issued on 7-27-2011.

Back to the Top

5. Continuity Data

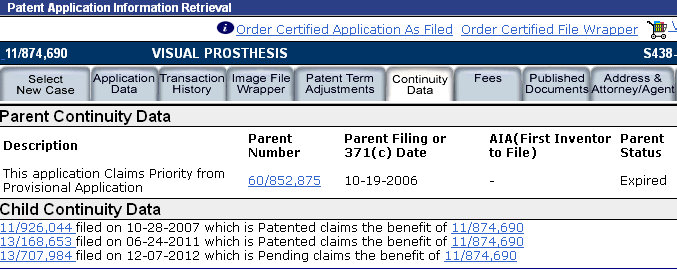

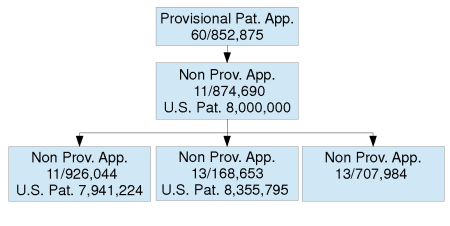

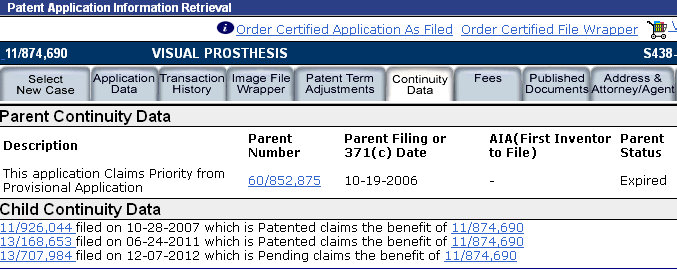

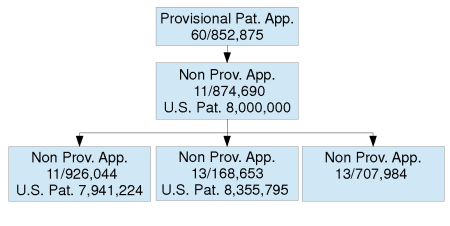

The Continuity Data Tab provides information about related patents or patent applications.

The application that resulted in US Patent 8,000,000, claimed priority to an earlier provisional patent application no. 60/852,875. Also downstream from the US Patent 8,000,000, are three patent applications (11/926,044, 13/168,653, 13/707,984) that claim priority to the application (11/874,690) that resulted in US Patent 8,000,000.

Back to the Top

6. Maintenance Fees

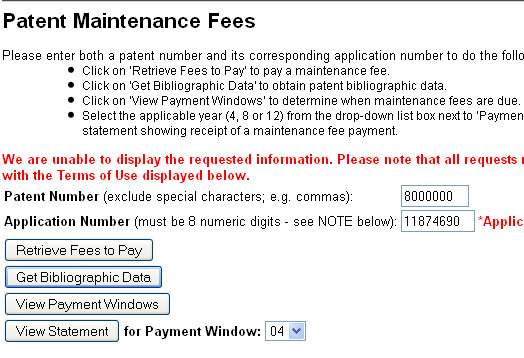

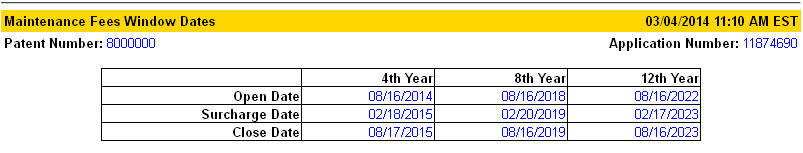

For utility patents, patent maintenance fees must be paid at 3 1/2, 7 1/2, and 11 1/2 years after the patent issues. If a patent has issued you can click on the Fees tab, where you are taken to the USPTO maintenance fee page.

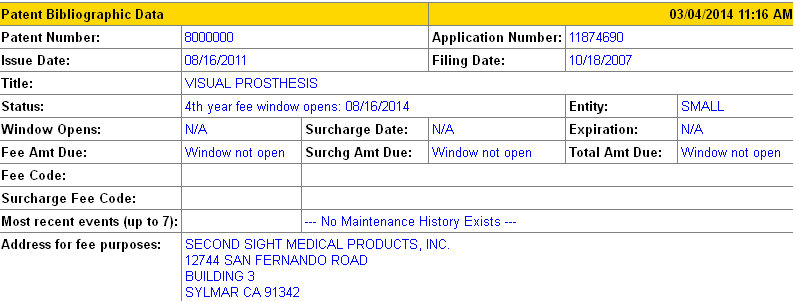

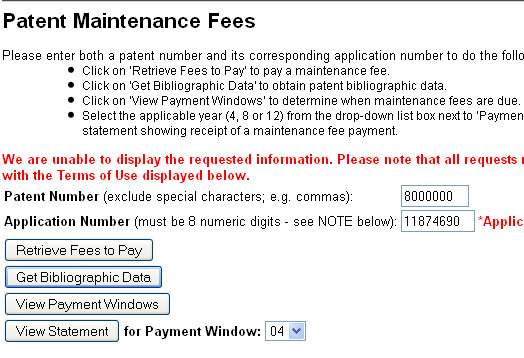

You must enter the patent number and the corresponding application number in order to retrieve maintenance fee information. Here the patent number is 8000000 and the corresponding application number is 11874690. By clicking the “view payment windows” a window similar to the following will be displayed.

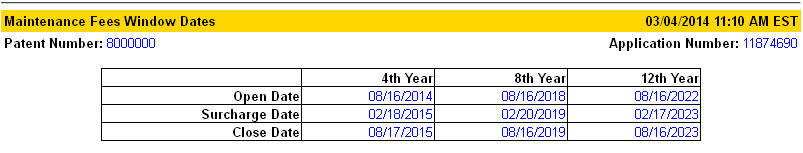

As the USPTO currently provides a six month grace period after the 3 1/2, 7 1/2, and 11 1/2 year deadlines, the USPTO references 4th, 9th, and 12th years rather than 3 & 1/2, 7 & 1/2, and 11 & 1/2 years. The widow when the payment can be made opens six months before the 3 1/2, 7 1/2, and 11 1/2 year date. The USPTO charges a surcharge for payments made in the six month grace period. Therefore the surcharge date is the day after the 3 1/2, 7 1/2, and 11 1/2 year date. The close date is 6 months after the 3 1/2, 7 1/2, and 11 1/2 year date.

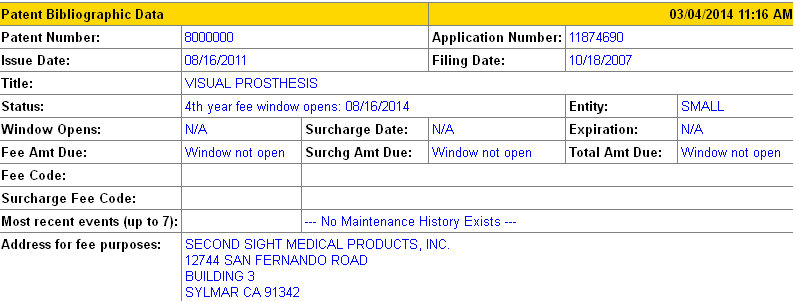

By clicking on the Get bibliographic Data button, you will receive information about whether any maintenance fees have already been paid. In the case of the Patent 8,000,000, no fees have yet been paid.

Back to the Top

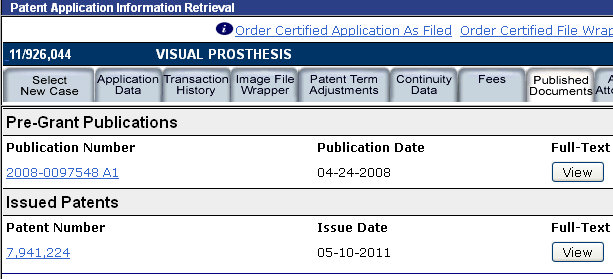

7. Published Documents

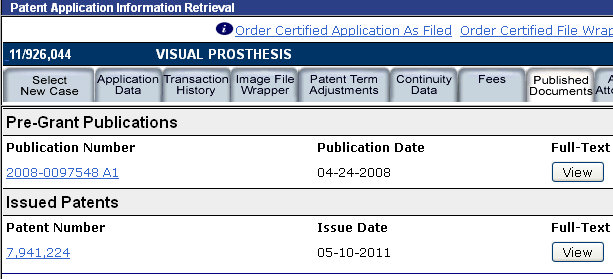

The published documents tab provides a list of publications related to application 11/874,690. In this case, the application was published as an application as US Pat Pub. 2008/0097548 A1 on April 24, 2008 and was published as a patent as US Pat 8,000,000 on May 10, 2011.

Back to the Top

8. Address & Attorney/Agent

The Address & Attorney Agent tab provides the current correspondence address for the patent or application as well as information about the patent attorney or agent representing the patent applicant / owner.

Back to the Top

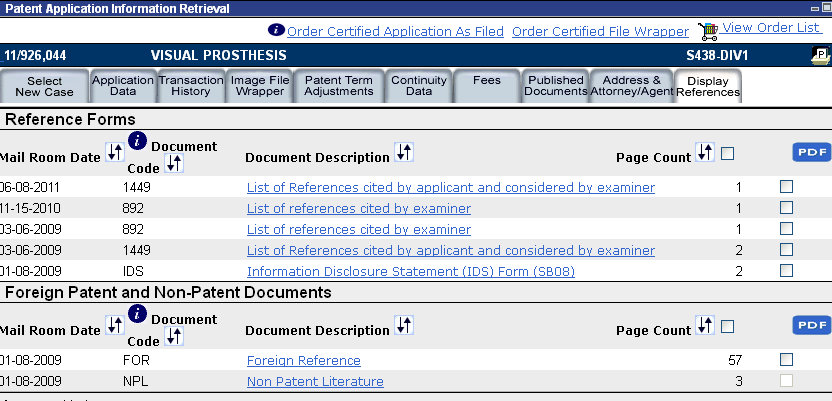

9. Display References

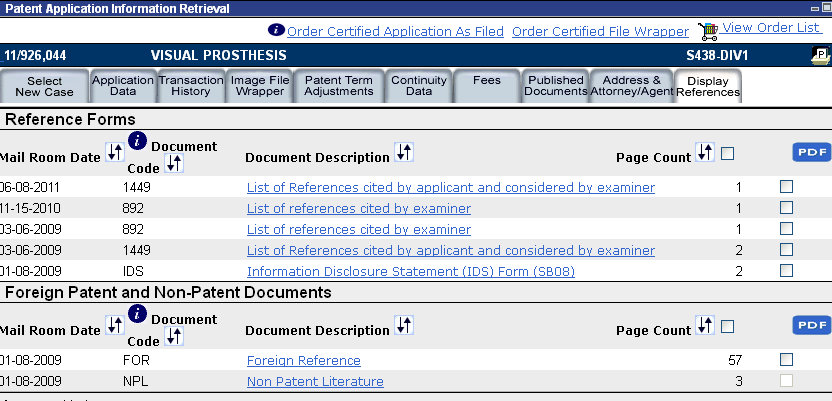

The display reference tab provides documents containing prior art references (such as patents, patent applications, publications, etc). This is a subset of the documents downloadable from the image file wrapper tab. The NPL is not downloadable as you can see that the box is grayed-out next to the NPL in the screen view below.

Back to the Top

10. Conclusion

Whether you want to check the status of your patent application or you want to learn more about an existing patent or published patent application, USPTO’s public PAIR system provides detailed information about such applications and patents.