The U.S. Supreme Court issued its decision in Alice v. CLS Bank (June 19, 2014) touching on the patent-eligibility of software implemented inventions. The decision continues to allow patent protection for software innovation and technological solutions implemented with software. Therefore all software patents are not dead in the wake of this opinion, in fact, most survive under the USPTO’s interpretation. However, this decision limits or eliminates, depending on the circumstances, the ability of one to obtain a patent covering a fundamental economic practice long prevalent in commerce that is merely implemented in a generic computer using generic functions without more.

The U.S. Supreme Court issued its decision in Alice v. CLS Bank (June 19, 2014) touching on the patent-eligibility of software implemented inventions. The decision continues to allow patent protection for software innovation and technological solutions implemented with software. Therefore all software patents are not dead in the wake of this opinion, in fact, most survive under the USPTO’s interpretation. However, this decision limits or eliminates, depending on the circumstances, the ability of one to obtain a patent covering a fundamental economic practice long prevalent in commerce that is merely implemented in a generic computer using generic functions without more.

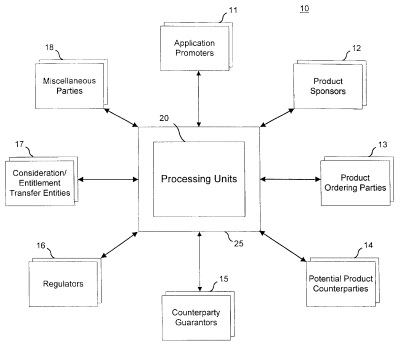

The patents at issue in Alice were directed to using a computer to mitigate financial settlement risk, i.e., the risk that only one party to an agreed-upon financial exchange will satisfy its obligation. The court found that all of  the claims at issue are drawn to “the abstract idea of intermediated settlement, and that merely requiring generic computer implementation fail[ed] to transform the abstract idea into a patent-eligible invention.”

Mayo Framework

The court followed the two step framework presented in Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., 566 U. S. ___ (2012), to determine whether the claims at issue were directed to an abstract idea. First, the Court determines whether the claims at issue are directed to a patent-ineligible concept (e.g. laws of nature, natural phenomena, or abstract ideas). If so, the second step is to determine whether there are additional elements in the claims that transform the nature of the claims into a patent-eligible application of the law of nature, natural phenomena, or abstract idea at issue.

Software is Still Patentable

The court asserted that the claims at issue in Alice did not improve the function of the computer itself, nor effect an improvement in any other technology or technical field. So at least software that does either of those things should be patent eligible. Further, the court acknowledged that it must tread carefully so that the rules about abstract ideas or other excluded subject matter do not swallow all of patent law. This is true because at some level all inventions use, reflect, rest upon, or apply laws of nature, natural phenomena, or abstract ideas. The court continued to recognize that the application of a law of nature, natural phenomena, or abstract idea to a new and useful end remains patent eligible.

Method Claims

The Court first looked at the method claims in Alice. In the first part of the Mayo framework, the court found that the method claims were directed to the abstract idea of intermediated settlement. The Court cited a 1896 publication discussing the use of a clearing-house as an intermediary to reduce settlement risk.

In the second part of the Mayo framework–whether there are additional elements–the court found that “the method claims, which merely require a generic computer implementation, fail to transform that abstract idea into a patent eligible invention.” The Court stated that the “wholly generic computer implementation is not generally the sort of ‘additional featur[e]’ that provides any practical assurance that the process is more than a drafting effort designed to monopolize the [abstract] idea itself.” The Court found that the method claims at issue did not do more than instruct the practitioner to implement the abstract idea of intermediated settlement on a generic computer.

The Court noted that the method claims did not improve the function of the computer itself, nor effect an improvement in any other technology or technical field. The Court found that all the computer steps were “well-understood, routine, conventional activities previously known to the industry.” Further, the Court found that the ordered combination of the steps using a generic computer added nothing that was not already present when the steps were considered separately.

The Court found that the computer readable medium claims failed for the same reasons as the method claims and because Alice conceded that the computer readable medium claims raise and fall with the method claims.

System Claims

The systems claims fared no better than the method and medium claims. The Court discounted arguments that the system claims were not abstract because they included specific hardware configured to perform specific computerized functions (“… a data storage unit having stored therein information….”, “a computer, coupled to said data storage unit, that is configured to…”, “a communications controller”, etc). The Court found these items were “purely functional and generic.” The Court stated that “Nearly every computer will include a ‘communications controller’ and a ‘data storage unit’ capable of performing the basic calculation, storage, and transmission functions…” Therefore, the Court found that the hardware recited by the system claims did not offer “a meaningful limitation beyond generally linking the use of the method to a particular technological environment.”

The Court found that the system claims were no different from the method claims in substance. The court stated, “The method claims recite the abstract idea implemented on a generic computer; the system claims recite a handful of generic computer components configured to implement the same idea.” The court stated that to interpret the method claims as patent-ineligible, but then interpret the system claims as patent-eligible would go against the Court’s previous precedent that section 101 should not be interpreted in ways that make patent eligibility depend on the patent draftsman’s art (e.g. the manner in which the claims are drafted).

Analysis: Generic Computer

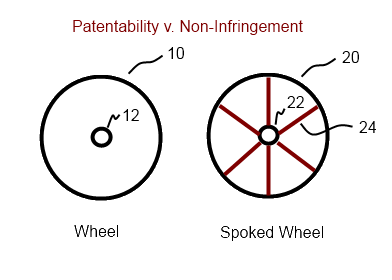

Some have argued that Court has imported the question of novelty, usually reserved for consideration under section 102 and 103, into the 101 patent-eligibility analysis under the second question: “whether there are additional elements in the claims that transform the nature of the claims into a patent-eligible application.”

The argument is that under the second step we must ask: are the additional components of the claim beyond the abstract idea old and well known? Whether something is old or well known if usually a questions determined under sections 102 and 103 by looking to see if the claimed subject matter is disclosed in the prior art or legally obvious in view of the prior art.

At least one commentator suggests that the court did not import a novelty test into the section 101 analysis, but instead presented a question of whether the claim does significantly more than state a fundamental principle connected with an instruction to “apply it.” The court said, “Stating an abstract idea while adding the words ‘apply it”’ is not enough for patent eligibility. Nor is limiting the use of an abstract idea “‘to a particular technological environment.” The Court said, “Stating an abstract idea while adding the words ‘apply it with a computer’ simply combines those two steps, with the same deficient result.” Therefore the reference to a generic computer not being enough is simply a recognition that Alice’s claim did no more than apply a old principle in a generic computer.

While the court provides that a generic computer is not enough to transform an abstract principle into patent-eligible subject matter, another commentator notes that the court does not provide much guidance on what is enough.

Not Abstract: Technological Solutions

As yet another commentator noted, the Court provided in Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175 (1981) that a process of curing rubber using a well known mathematical equation was patent-eligible not because it involved a computer, but because the claimed process improved an existing technological process. Therefore, inventions directed at improving a technological problem should not be found to be abstract under section 101.

The question arises, what is a technological problem? At least the areas of applied economics and finance, such as intermediated settlement, which provide a non-technical method of organizing human activity are excluded from the meaning of technological.

USPTO Interprets Alice

On June 25, 2014, the USPTO issued a memo to its patent examiners instructing how to apply the ruling in Alice to pending patent applications. The memo instructs examiners to follow the two step Mayo analysis. The memo provides these examples of abstract ideas referenced in Alice under the first step of Mayo:

- Fundamental economic practices

- Certain methods of organizing human activities

- An idea itself

- Mathematical relationships/formulas

The memo instructs that inventions are not patent ineligible simply because the invention involves an abstract concept. The application of an abstract idea in a meaningful way is patent eligible.

If any of the above abstract ideas are found in the claims, the Examiner must proceed to the second step of Mayo to determine whether the claim is nonetheless patent eligible because it has additional elements that amount to significantly more than the abstract idea itself. Examples of limitations that may be enough to qualify as significantly more when recited in a claim with an abstract idea include:

- Improvements to another technology or technical field

- Improvements in the functioning of the computer itself

- Meaningful limitations beyond generally linking the use of an abstract idea to a particular technological environment

The USPTO noted that limitations that are not enough to qualify as significantly more include:

- Adding the words “apply it” (or an equivalent) with an abstract idea, or mere instructions to implement an abstract idea on a computer

- Requiring no more than a generic computer to perform generic computer functions that are well-understood, routine, and conventional activities previously known to the industry.

Conclusion

While patent protection for software directed to fundamental principles of economics and finance without more is limited, patent eligibility for protecting software innovation and technological solutions implemented with software is still alive after Alice.