The way that a design is presented in a design patent is critical. Design patent drawings are often line drawings. But photographs are also allowed. And some patents use computer generated images.

Yet, while photographs and computer generated images may provide more details than line drawings, they are likely to be more limiting. The more details in the design drawings the more possible differences a competitor could develop. Details in a design patent are a double edged sword, more details provide increased options for distinguishing prior art, but may result in more narrow protection as shown in the case below.

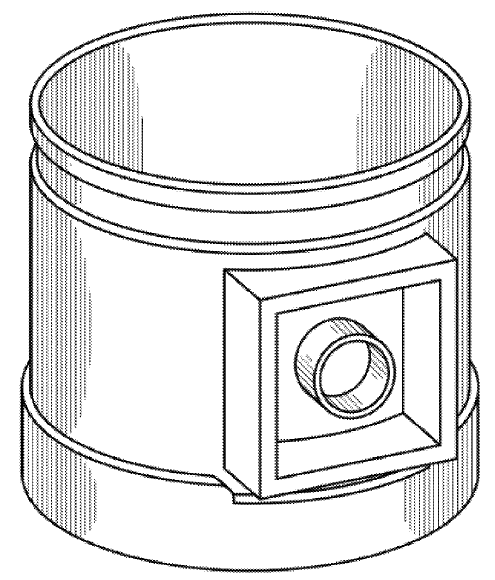

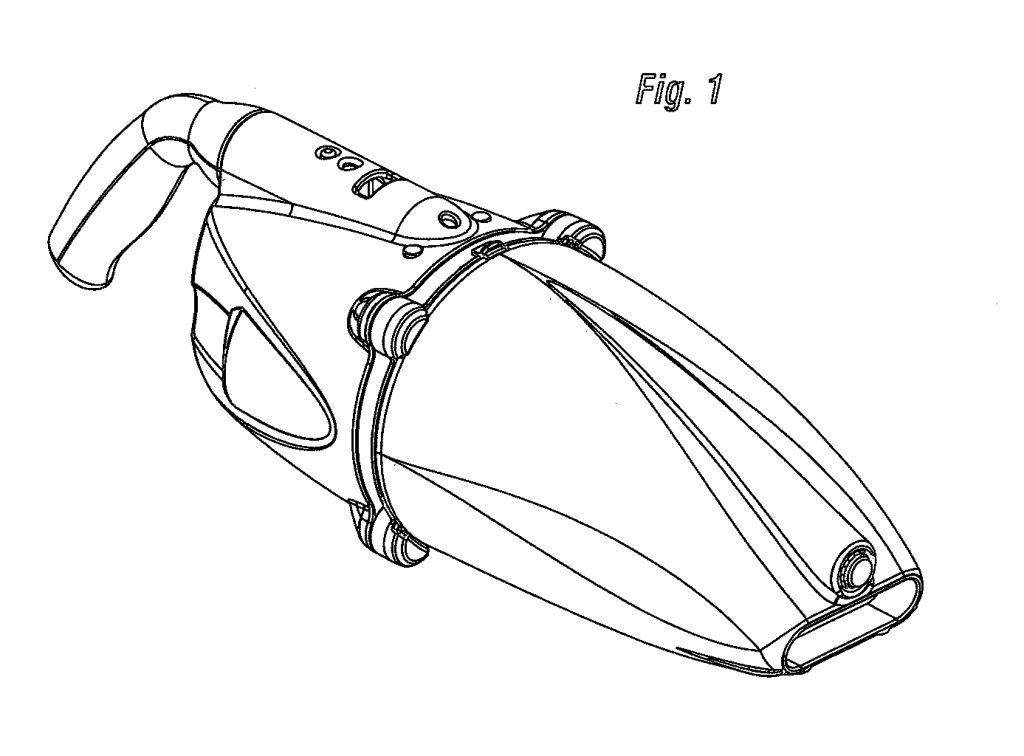

Think Green Ltd. sued Medela AG asserting that Medela’s breast pump infringed its design patent US D808,006 (the ‘006 Patent). Below is figure 9 (first/left) from the ‘006 patent and Medela’s pump (second/right).

Medela’s pump is transparent. The images of the ‘006 patent are computer generated images. Think Green argued that the ‘006 patent covered transparent objects. The court disagrees.

According to MPEP rules, surface shading lines are used to “indicate “character and contour,” including “to distinguish between any open and solid areas of the article.” On the other hand, the court notes that other “courts have held that when a patent fails to specify a limitation, in other words, when it is blank and does not include surface shading, the patentee is entitled to the broadest reasonable construction.” For example, in an older case from the 6th Circuit, that court found a blank surface without oblique lines could claim a transparent, translucent, or opaque surface, or both. Transmatic, Inc. v. Gulton Indus., Inc., 601 F.2d 904, 912-13 (6th Cir. 1979).

The court in the Think Green case concluded “an inventor intending to claim a generically opaque surface, and not any particular material type, would use a line drawing with a blank surface, free of anything but contour lines, thereby claiming both an opaque and transparent surface.” Therefore, the court found the ‘006 Patent computer generated images “must be interpreted to claim an opaque object to the exclusion of translucent or transparent objects.”

The court then found that Medela’s pump was not substantially the same as the design of the ‘006 Patent and did not infringe. The court said:

“Even if Medela’s product were exactly the same as Think Green’s design in all other aspects, the Court finds that an ordinary observer would not find the translucent object to be substantially the same as the opaque object. Opaque and translucent objects are categorically different such that they are “plainly dissimilar” and could not be confused by an ordinary observer. … Indeed, whether an object is opaque or translucent is one of the most obvious and prominent characteristics of any object.” Think Green Ltd. v. Medela AG, No. 21 C 5445, 2022 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 184040 (N.D. Ill. Oct. 7, 2022)

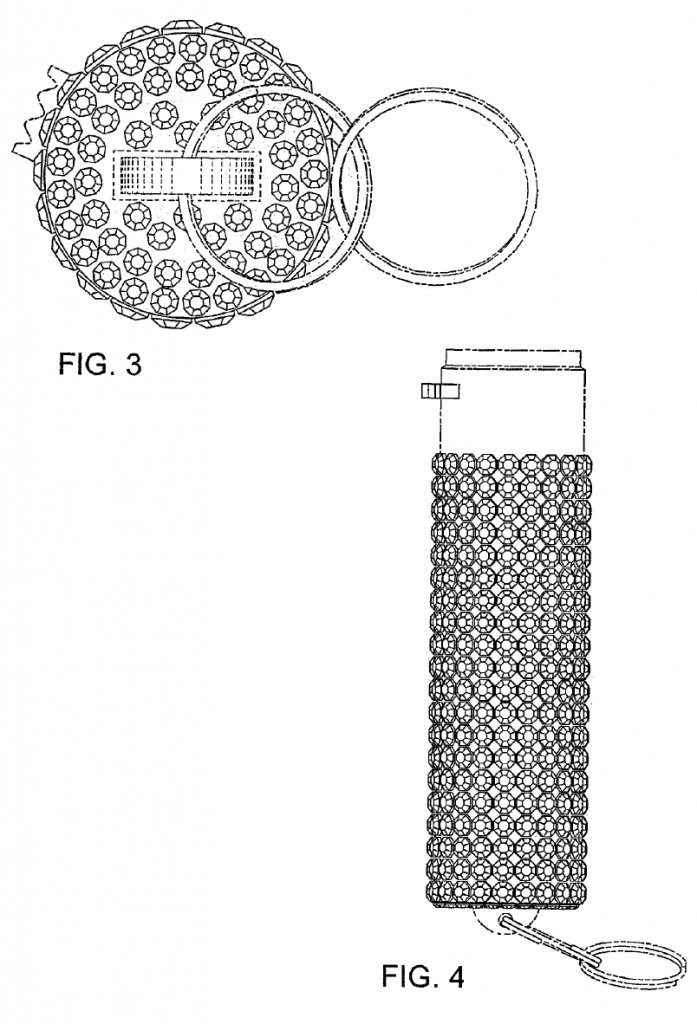

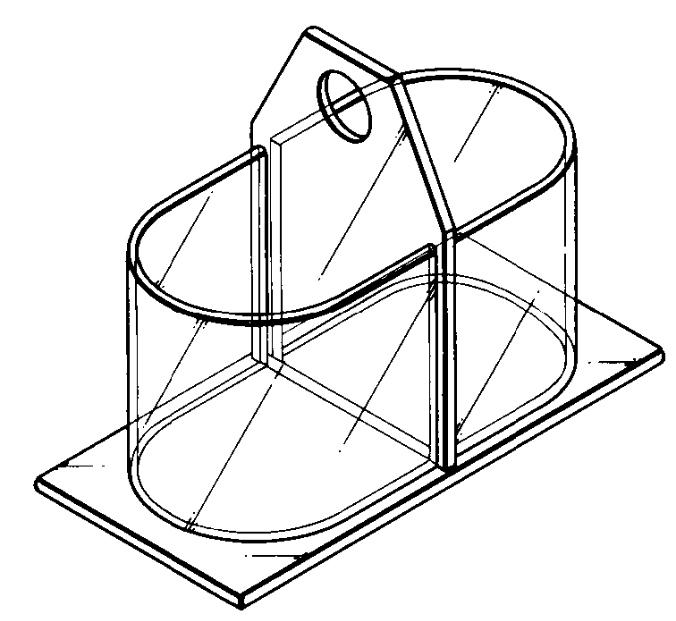

Now, compare the drawings of the ‘006 patent to the following drawings from two patents owned by Lego A/S.

The first drawing (left) from US Patent D951366 (‘366 patent) shows a toy building element presented in a traditional black and white line drawing. The second drawing (right) from US Patent D951365 (‘365 patent) is a photograph, showing the toy building element is transparent or at least translucent.

The ‘365 patent clearly covers a transparent or translucent toy building element, but probably does not cover an opaque product under the reasoning in the Think Green case.

But does the ‘366 patent cover transparent or translucent products? The reasoning in the Transmatic, Inc. and Think Green cases indicates it does.

Yet, the MPEP provides that “oblique line shading must be used to show transparent, translucent and highly polished or reflective surfaces, such as a mirror.” MPEP 1503.02(II).

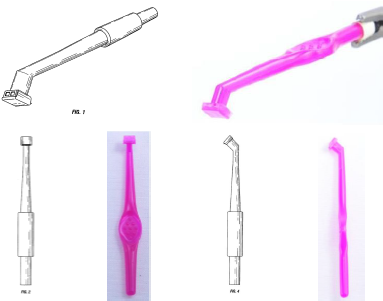

What is oblique line shading? The following is an example of oblique line shading for black and white line drawings showing transparent surfaces, from the USPTO Design Patent Application Guide:

.

Does the failure to use oblique line shading in line drawings limit the claimed design to opaque surfaces? A number of district courts have said no and followed Transmatic.

One court said: “the relevant section [1503.02(II)] of the MPEP only specifies that an inventor wishing to limit a particular surface to a transparent, translucent, or reflective material must indicate the surface through the use of oblique lines. It does not state that failure to include oblique lines necessarily excludes the use of a transparent surface.” Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 11-CV-01846-LHK, 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 105125, at *24-25 (N.D. Cal. July 27, 2012). Other district courts have agreed in Water Tech., LLC v. Kokido Dev. Ltd., No. 4:17-cv-01906-AGF, 2019 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 42420, at *42-44 (E.D. Mo. Mar. 15, 2019) and Lifted Ltd., Ltd. Liab. Co. v. Novelty Inc., Civil Action No. 16-cv-03135-PAB-GPG, 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 92102, at *19-20 (D. Colo. May 27, 2020).

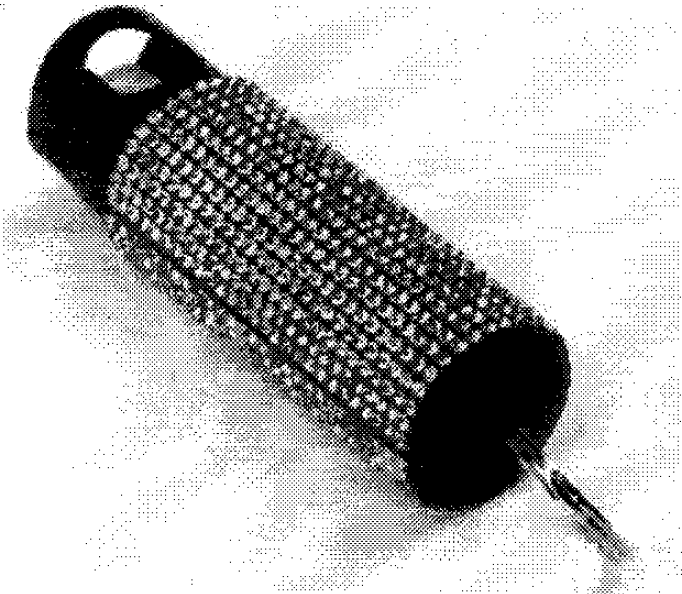

The drawings of design patent D556396 in the Water Tech case that were construed to encompass both opaque and transparent surfaces includes:

Why would Lego file for the ‘356 patent with photos of the transparent product if the line drawing version in the ‘366 patent is sufficient to cover transparent and opaque surfaces according to the cases above? There are at least a few reasons. First, if the prior art invalidates the broader line drawing version of the ‘366 patent, possibly the ‘365 patent would survive on the basis of the specifically claimed transparency (there is some uncertainty on this issue as well but see In re Haruna, 249 F.3d 1327 (Fed. Cir. 2001)). Second, it appears the Federal Circuit has not ruled directly on whether line drawings cover transparent and opaque surfaces. Therefore, if the Federal Circuit would decide line drawings do not cover transparent surfaces or the law would otherwise change in this direction, Lego would be covered by the patent specifically showing transparency. Third, possibly it makes it easier marginally to succeed on a patent infringement case because the transparency in the design patent drawings makes them look more like the accused transparent product. In theory this last aspect should not matter if a judge instructs that the design patent covers transparent and opaque surfaces. Yet, it nevertheless may be marginally easier.

Appropriate line drawings provide a better chance of covering transparent surfaces as compared to photos or computer images of products with opaque surfaces. Yet, if transparent surfaces are important to the design, they can be specifically indicated in the drawings by the use of oblique line shading and accompanying text description or a photo showing a transparent product such as in Lego’s ‘365 patent above.