“Its patented.” “They have a patent on it.” “It’s patent pending.” “You cannot sell that because I have a patent on it.”

“Its patented.” “They have a patent on it.” “It’s patent pending.” “You cannot sell that because I have a patent on it.”

Many statements get thrown around in the marketplace about patent rights.

But what do these statements mean? Are these statements being used correctly? What rights does the competitor actually have?

If you are faced with claims that a competitor has a patent or has patent pending, you want to know the impact to your business and your ability to compete.

Does my competitor have a patent or just a pending application?

Often times you hear “I have a patent” or “It’s patented”, when the competitor merely has a patent application filed. Also, “I have a provisional patent” is often used. But there’s no such thing as a provisional patent. The speaker probably means “I have a provisional patent application.”

So the first step is to determine whether the competitor has a granted patent or only a pending patent application.

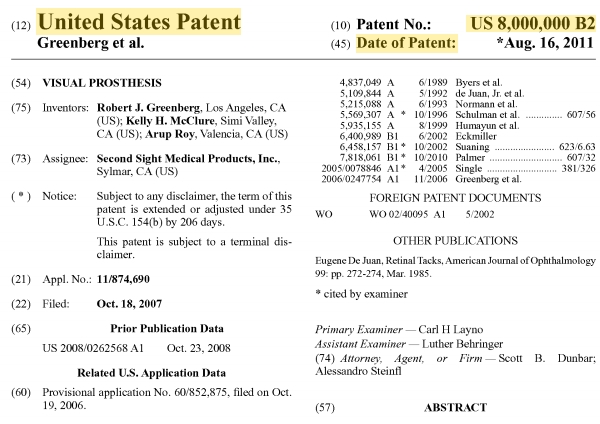

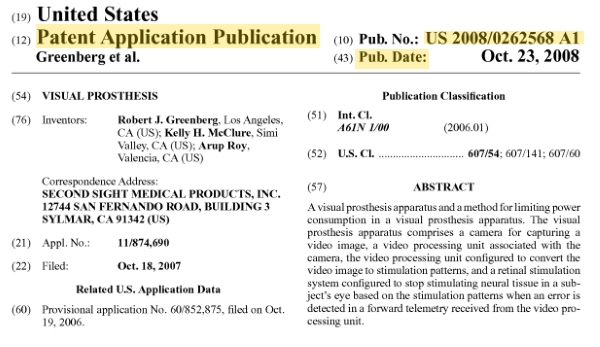

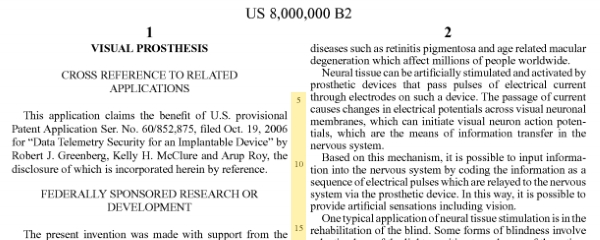

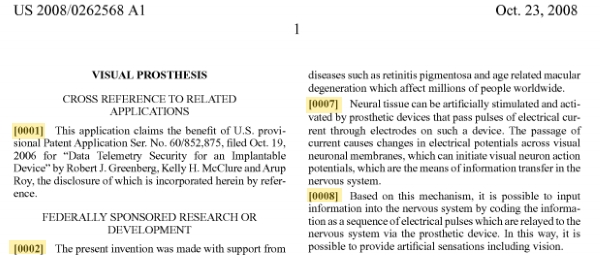

Patent law encourages patent owners to mark their products/services with an indication that the product/service is covered by a granted patent. If you have a patent number then it’s obvious that there is a patent. However, you need to make sure the number is a patent number for a granted patent, and not a patent application number or a patent application publication number.

Granted patents look somewhat similar to published patent applications. So, published patent applications are often believed to be issued patents, but the published patent application is merely a pending application that might or might not become a patent.

Not every patent application results in a patent. Even if the competitor has a pending patent application, the competitor might not ultimately obtain a patent.

On the other hand the competitor might indeed obtain a patent. Therefore, it is important to investigate claims that a product is “patented” or that a patent application is filed.

But, don’t give up at the mere mention of a patent. The competitor might not obtain a patent, as I mentioned. Or the competitor might only get a very narrow patent that doesn’t cover your product.

How do I know whether a patent application has been filed?

If the product or product packaging or advertising material related to the product or service provides “patent pending,” that’s a good indication that a patent application has been filed on at least some part of the product or service.

However, sometimes product or service material is not marked with “patent pending.” So the absence of “patent pending” alone is not enough to know you are in the clear.

Another way that you might find out that the competitor has a patent application is if you hear this from others in the industry or marketplace.

Once you have some indication that a patent application is filed, you can do a search of the published patent applications to determine whether the application in question is publicly available.

Patent applications are generally secret (not published) for 18 months after they are filed. So it’s possible that you won’t be able to find the competitors patent application even though it is filed.

My competitor’s patent application is secret: What can I Do?

If you know or suspect that the competitor has a patent application filed, but you can’t find the competitors patent application, then it’s possible that the application is secret.

If the application is secret, you can have a prior art search performed to determine if there are any safe harbors that will give you freedom to operate.

What is a prior art safe harbor?

Safe harbors are often found in descriptions of old expired patents. Safe harbors can also be found in other publications and other prior art. Since patents are only granted on inventions that are new, expired patents disclose configurations that are not capable of being patented without new additions or features. These areas that are not capable of being patented are the safe harbors.

It is not possible to “re-patent” an invention. But, it is possible that a competitor or third party could come up with a new variation, new feature, or other new attribute of an old invention that could be patented. Even if the competitor gets a patent on the new variation, new feature, or other new attribute, that patent could not cover the old unmodified invention described in the old expired patent.

So you have to look at old patents very carefully to determine what is a safe harbor, i.e. what cannot be patented because it is old.

The end goal of a prior art safe harbor analysis is to determine whether your product is squarely described in an old expired patent(s) (or other prior art) so that it is unlikely that your competitor’s patent application could cover your product.

My competitor’s patent application is publicly available

If the patent application is publicly available, you can have a patent attorney review the contents of the patent application to determine what the competitor is seeking patent protection on.

It is often difficult to predict exactly what patent coverage the competitor could obtained under a pending patent application. This is because the patent applicant can amend the claims of the patent application during the negotiation stage (prosecution stage) with the Patent Office. Amendments to the claims often change the scope of patent protection claimed. Therefore analyzing a pending patent application is somewhat like hitting a moving target, i.e. it can be difficult to predict the scope of the patent claims.

However, as described above, a prior art search can be conducted to determine the safe harbors that provide you freedom to operate.

My competitor has a patent

If you know the patent number of the competitors patent, a patent attorney can review the patent to determine whether it could potentially cover your product/service and create a risk of patent infringement.

This analysis involves reading the patent and understanding the meaning of the claim terms, as well as studying the file history where the applicant communicated with the patent office about the patent application. Often the analysis also includes reviewing prior art patents to determine what is old (a safe harbor) and cannot be covered by the patent.

If it appears that one or more patent claims covers your product, it is possible to do a prior art search to determine whether or not those claims are valid.

If prior art discloses all the elements of the competitor’s patent claim at issue, then it is possible to obtain an attorney’s opinion that the claim is not valid. This is called an invalidity opinion. If the patent claim is not valid, it should not be able to be enforced against you.

However, there’s always a risk that the patent owner could disagree with your invalidity position and could sue you. Patent claims are presumed to be valid. So, the burden is on you to show that the patent claim is invalid.

Conclusion

Claims that your competitor has patent rights should be investigated. This article covered some of the steps one might take when faced with a competitor’s patent claim.

Photo credit to flickr user zepfanman under this creative commons license. The photo above is cropped from the original photo.

In 1998, Erich Specht formed Android Data Corporation (ADC) and began selling e-commerce software under the trademark Android Data. ADC later transferred its assets, including the trademark, to Andriod’s Dungeon Inc. (ADI), which was owned by Specht. In 2009, Specht and ADI filed a trademark infringement lawsuit against Google based on Google’s use of the Android mark to refer to its mobile operating system. But Specht and ADI lost.

In 1998, Erich Specht formed Android Data Corporation (ADC) and began selling e-commerce software under the trademark Android Data. ADC later transferred its assets, including the trademark, to Andriod’s Dungeon Inc. (ADI), which was owned by Specht. In 2009, Specht and ADI filed a trademark infringement lawsuit against Google based on Google’s use of the Android mark to refer to its mobile operating system. But Specht and ADI lost. Farzad and Lias Tabris were auto brokers. They operated websites at buy-a-lexus.com and buyorleaselexus.com connecting buyers with dealers selling Lexus vehicles.

Farzad and Lias Tabris were auto brokers. They operated websites at buy-a-lexus.com and buyorleaselexus.com connecting buyers with dealers selling Lexus vehicles.

“Its patented.” “They have a patent on it.” “It’s patent pending.” “You cannot sell that because I have a patent on it.”

“Its patented.” “They have a patent on it.” “It’s patent pending.” “You cannot sell that because I have a patent on it.” Clients often wonder why a patent application on a relatively simple invention is relatively long. The answer is that even the most simple inventions are not simple to describe properly in a patent application.

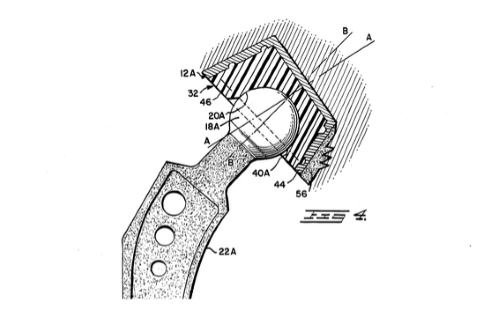

Clients often wonder why a patent application on a relatively simple invention is relatively long. The answer is that even the most simple inventions are not simple to describe properly in a patent application. In

In  Spirits of New Merced (“Spirits”) applied to register the trademark YOSEMITE BEER for the sale of beer. But the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) refused to register the mark.

Spirits of New Merced (“Spirits”) applied to register the trademark YOSEMITE BEER for the sale of beer. But the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) refused to register the mark. British Bulldog Ltd. applied to register the trademark PLAYERS on the goods of men’s underwear. The trademark examiner  refused to register the mark claiming that it conflicted with a previously registered mark PLAYERS for the goods of shoes.

British Bulldog Ltd. applied to register the trademark PLAYERS on the goods of men’s underwear. The trademark examiner  refused to register the mark claiming that it conflicted with a previously registered mark PLAYERS for the goods of shoes.