Erik Brunetti acquired ownership of a trademark application to register the mark FUCT for apparel. The USPTO refused to register the mark under section 2(a) of the Lanham Act asserting that it was immoral or scandalous. But the Federal Circuit found that the provision banning registration of marks comprising immoral or scandalous matter violated the First Amendment. In re Brunetti, no. 2015-1109 (Fed. Cir. 2017). This clears the way for FUCT to register, unless the government appeals this ruling.

Erik Brunetti acquired ownership of a trademark application to register the mark FUCT for apparel. The USPTO refused to register the mark under section 2(a) of the Lanham Act asserting that it was immoral or scandalous. But the Federal Circuit found that the provision banning registration of marks comprising immoral or scandalous matter violated the First Amendment. In re Brunetti, no. 2015-1109 (Fed. Cir. 2017). This clears the way for FUCT to register, unless the government appeals this ruling.

The Brunetti case follows the Matal v. Tam, No. 15-1293 (2017)Â case where the Supreme Court struct down as violating the First Amendment another provision of section 2(a), which barred the registration of marks consisting of material that is disparaging. The outcome in Brunetti is not surprising in light of Tam.

In Brunetti, the court found that evidence supported that FUCT was vulgar as being a phonic twin of “fucked.” Therefore FUCT was scandalous under section 2(a).

But, the court found that the immoral or scandalous bar of section 2(a) was an unconstitutional content-based restriction on speech.

Trademarks Have Expressive Content

The court noted that marks considered immoral or scandalous can have expressive content. The court cited the following examples of marks espousing a powerful cause: FUCK HEROIN; FUCK CANCER; and FUCK RACISM. And the court noted these marks conveying a political view: DEMOCRAT.BS and REPUBLICAN.BS. The court said that “powerful messages can sometimes be conveyed in just a few words.”

The court found that there is no question that the immoral or scandalous prohibition targets the expressive components of speech. And this content-based restriction is disconnected from the purpose of trademark registration, which is to facilitate the source identification of goods and services and avoid consumer confusion in the marketplace.

There was no dispute that the immoral and scandalous provision could not survive First Amendment strict scrutiny. The court further found that it could not survive intermediate scrutiny.

Trademark registration is not a government subsidy or a limited public forum

The government argued that the First Amendment was not implicated because the trademark registration program is either a government subsidy or a limited public forum. The Court rejected both of these arguments.

On the subsidy issue, the court found that trademark registration does not implicate Congress’ power to spend funds and that the grant of a trademark registration is not a subsidy equivalent.

On the limited public forum issue, the court found that the speech that “flows from trademark registration is not tethered to a public school, a federal workplace, or any other government property.” Further, it said, “If the government can constitutionally restrain the expression of private speech in commerce because such speech is identified in a government database [e.g. the trademark registration database], so too could the government restrain speech occurring on private land or in connection with privately-owned vehicles, simply because those private properties are listed in a database.”

On Judicial Review

The court cited to the article by Anne Gilson LaLonde & Jerome Gilson titled Trademarks Laid Bare: Marks That May Be Scandalous or Immoral, 101 Trademark Rep. 1476 (2011). This article considers the problems of the immoral or scandalous provision and reviews numerous examples of marks rejected and not rejected under that provision. One of the solutions proposed by the article is for Congress to repeal the scandalous and immoral prohibitions from the statute. But the article states:

No lawmaker would be willing to suggest even tinkering with a ban of any sort on immoral or scandalous material. Asking to be tagged as pro-immorality or pro-vulgarity is not a savvy political move. And advocating repeal of a century-old statutory phrase designed to protect public sensibilities would doubtless trigger impassioned opposition.

Therefore, the courts are likely the only place where the scandalous and immoral provision could be addressed.

Public Sensibilities Protected?

But did the immoral or scandalous bar provision really “protect the public sensibilities?” In Brunetti, the government argued that it had a substantial interest in protecting the public from scandalous or immoral marks. But as the court noted, whether a trademark is registered or not, does not stop someone from using such a mark in the marketplace. You can use a mark without registration it. And, the court said:

“In this electronic/Internet age, to the extent that the government seeks to protect the general population from scandalous material, with all due respect, it has completely failed.”

Impact of the Decision

Before this decision, as noted by the court, the marketplace included scandalous material and scandalous marks. In fact, Mr. Brunetti claimed that he operated his clothing brand under the FUCT mark for over 20 years. The lack of registration didn’t stop him from operating all that time and exposing the public to his mark.

After this decision, looking to the trademark registration database, you might see more scandalous, vulgar, or shocking marks. But will that have a great impact?

As the Laid Bare article stated, “The marketplace would ideally deal with the most offensive marks, as consumers would presumably refuse to purchase goods sold under marks that offend them. The American public would continue, as it is now, to be faced with products, services, entertainment and printed matter that are in poor taste and even embarrassing to behold.”

The Court said that “Many of the marks rejected under § 2(a)’s bar on immoral or scandalous marks … are lewd, crass, or even disturbing.” The Court continued that it “was not eager to see a proliferation of such marks in the marketplace.” But, “There are countless songs with vulgar lyrics, blasphemous images, scandalous books and paintings, all of which are protected under federal [copyright] law.” And, “The First Amendment… protects private expression, even private expression which is offensive to a substantial composite of the general public.”

Obscene Material

The court left open the possibility that a provision barring marks comprising obscene material could be constitutionally permissible.

The government might appeal this ruling to the Supreme Court and argue that the immoral and scandalous provision should be interpreted narrowly to cover only marks comprising obscene material. It seems unlikely that the court will take that appeal following Tam.

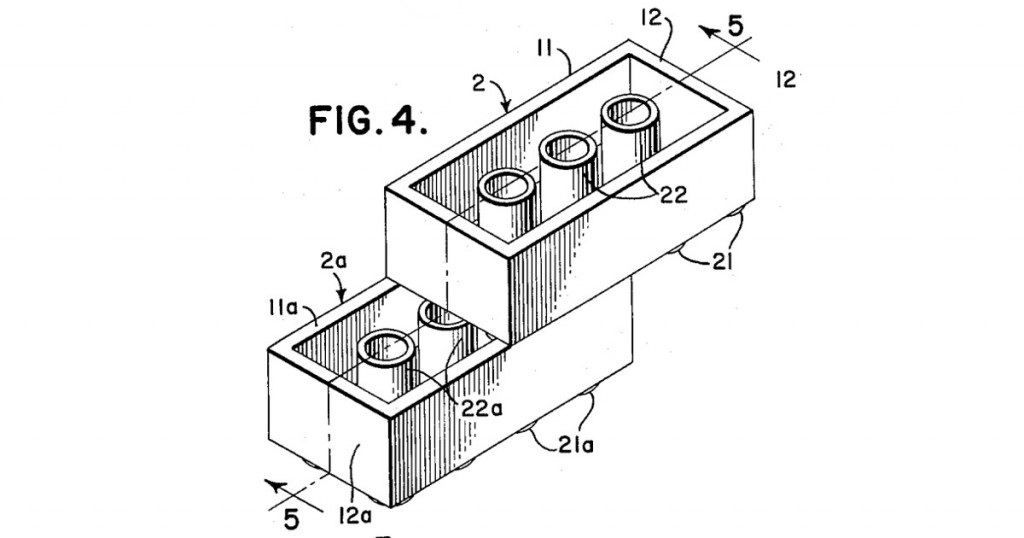

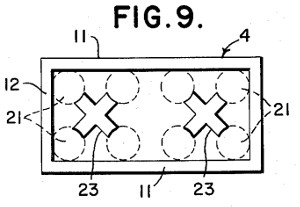

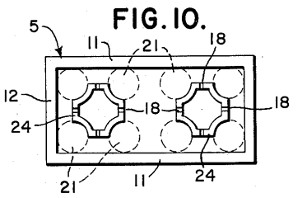

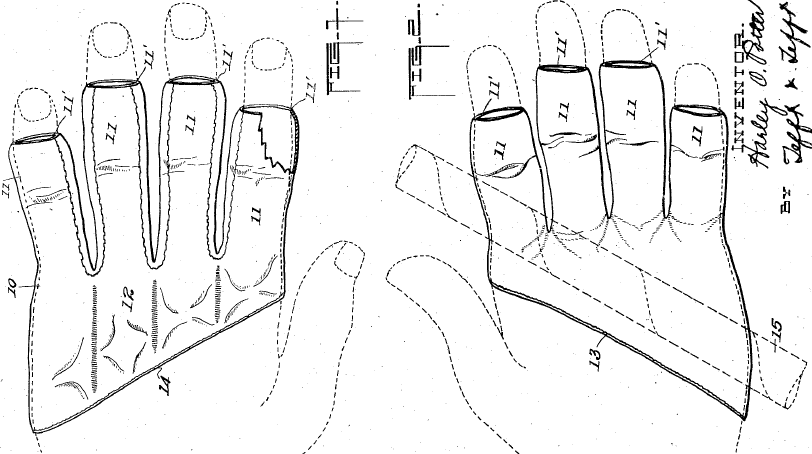

Â Figure 10 shows an alternative block having somewhat star-snapped projections 24.

Figure 10 shows an alternative block having somewhat star-snapped projections 24.

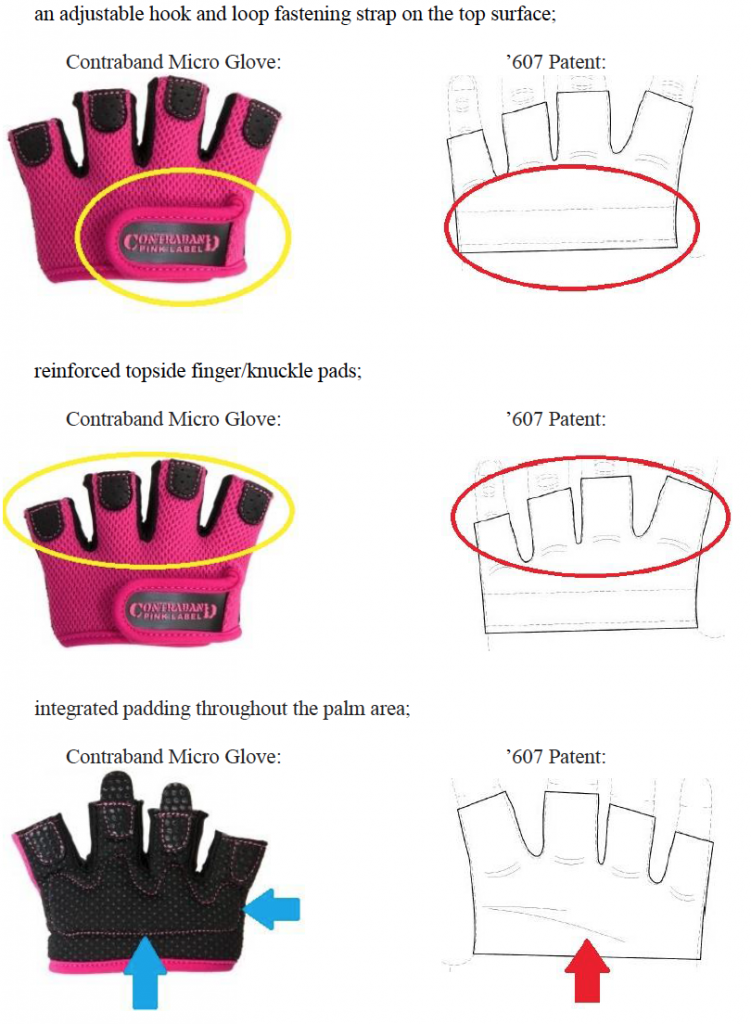

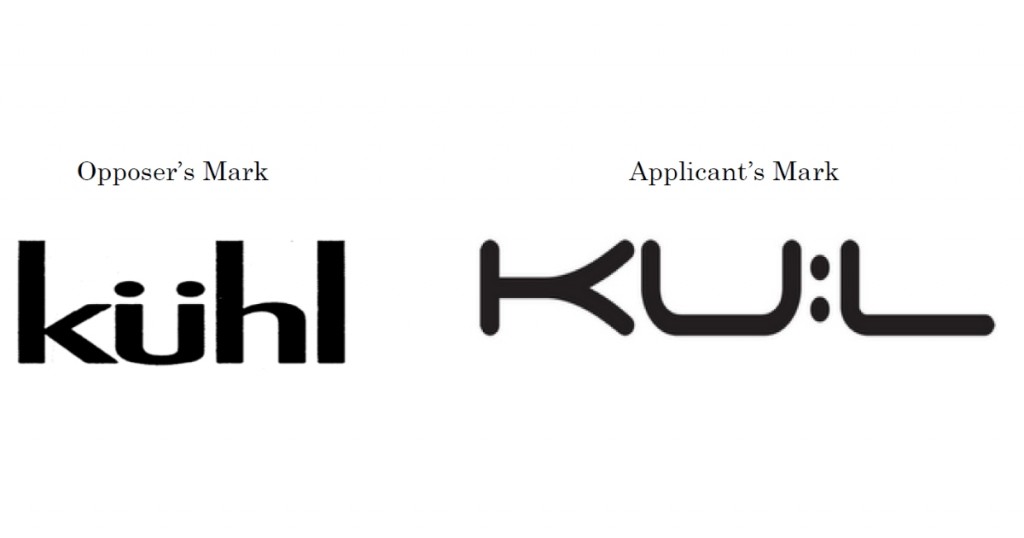

Yesterday, I wrote about Contraband Sports LLC’s

Yesterday, I wrote about Contraband Sports LLC’s

Mainstream Property Group, LLC applied to register the mark NEXT HOMES Â for providing assisted living facilities as well as for providing long-term care facilities and short term rehab facilities for seniors. NextHome, Inc. opposed the application based on its NEXTHOME mark, which was registered for real estate brokerage services.

Mainstream Property Group, LLC applied to register the mark NEXT HOMES Â for providing assisted living facilities as well as for providing long-term care facilities and short term rehab facilities for seniors. NextHome, Inc. opposed the application based on its NEXTHOME mark, which was registered for real estate brokerage services.

Erik Brunetti acquired ownership of a trademark application to register the mark FUCT for apparel. The USPTO refused to register the mark under section 2(a) of the Lanham Act asserting that it was immoral or scandalous. But the Federal Circuit found that the provision banning registration of marks comprising immoral or scandalous matter violated the First Amendment.

Erik Brunetti acquired ownership of a trademark application to register the mark FUCT for apparel. The USPTO refused to register the mark under section 2(a) of the Lanham Act asserting that it was immoral or scandalous. But the Federal Circuit found that the provision banning registration of marks comprising immoral or scandalous matter violated the First Amendment.

Boyd Coddington’s Hot Rods & Collectibles filed an application to register the trademark BOYD’S for apparel. But the USPTO examining attorney refused the registration based on a likelihood of confusion with the prior mark BOYDS for clothing. The TTAB affirmed the refusal finding the marks were virtually identical and the apostrophe was inconsequential in comparing the marks.

Boyd Coddington’s Hot Rods & Collectibles filed an application to register the trademark BOYD’S for apparel. But the USPTO examining attorney refused the registration based on a likelihood of confusion with the prior mark BOYDS for clothing. The TTAB affirmed the refusal finding the marks were virtually identical and the apostrophe was inconsequential in comparing the marks.