After a patent application is filed, the application will be placed in a queue to be examined by a patent examiner at the patent office. The patent examiner’s job is to ensure that only patent applications that meet the legal requirements for patentability are allowed to become patents.

According to some estimates between about 77% to 95% of all patent applications receive at a least one type of rejection or objection during the first examination by a patent examiner. Therefore it is quite common to receive such a rejection or objection in a patent application. Many such objections or rejections can be overcome by a proper response as explained below.

I. Formalities

Before turning to substantive rejections, which consider whether the invention is new as compared to the prior art or whether the subject matter of your invention is patentable, first we will consider objections based on formality requirements.

Parts of A Utility Patent Application

Section 600 of the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP) sets out the component requirements for a utility patent application. For the purpose of this article, we will focus on the specification, the drawings, and the claims. The MPEP provides that the specification should include the following sections in order:

- Title of the Invention.

- Cross-References to Related Applications.

- Statement Regarding Federally Sponsored Research or Development.

- The names of the parties to a joint research agreement.

- Reference to a “Sequence Listing,†a table, or a computer program listing appendix submitted on a compact disc and an incorporation-by-reference of the material on the compact disc (See 37 CFR 1.52(e)(5)). The total number of compact discs including duplicates and the files on each compact disc must be specified.

- Background of the Invention.

- Field of the Invention.

- Description of the related art.

- Brief Summary of the Invention.

- Brief Description of the Several Views of the Drawings.

- Detailed Description of the Invention.

- Claim or Claims.

- Abstract of the Disclosure.

- “Sequence Listing,†if on paper.

Some of the above sections only apply to certain types of applications, but every application generally includes at least a title of the invention, a background of the invention, a brief description of the invention, a brief description of the drawings, a detailed description of the invention, a claim or claims, and an abstract. Therefore if any required section of the specification is not provided the examiner may raise an objection and require that the section be added or that a heading inserted so that all of the sections that are required are in the specification.

However no new subject matter can be added to the application after it is filed. Therefore, if, for example, the abstract is left out of the application at the time it was filed an abstract can probably be written an added based on subject matter disclosed in the rest of the description of the application. Therefore the subject matter of the abstract would not be new as compared to what was originally disclosed.

Features claimed but not shown in the drawings

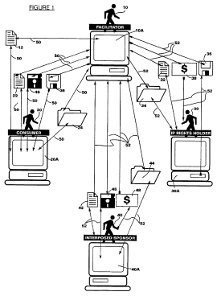

In many cases in order for a feature to be claimed in a patent application it must be shown in the drawings. This is not always true for her example with respect to inventions that don’t require any drawings, such as certain chemical inventions. However, many if not most patent applications include one or more drawings that accompanied the description to help the reader understand the invention. See MPEP 608.02. If the invention is of the type that is capable of being shown in drawings then any claimed feature should also shown in the drawings.

Drawings

A detailed discussion of how drawings should be drafted in order to comply with patent offices requirements is outside the scope of this article. However the rules at 37 CFR 1.84 set forth the standards for patent drawings. Further the USPTO created a Guide for Preparation of Patent Drawings dated June 2002 which is a good resource for resolving questions regarding patent drawings.

Claims

Every non-provisional application must include at least one claim. If the patent application does not have a claim the USPTO will not provide the applicant with a filing date. Claims are the most difficult and important portions of a patent application to draft properly. One of the most common objections raised with respect to claims is that a feature or element described in the claim lacks an antecedent basis, which is explained in MPEP section 2173.05(e).

A claim lacks an antecedent basis, for example, when a claim refers to ‘the lever’ or “said lever, where the claim contains no earlier recitation or limitation of a lever. Every element in a claim must be introduced starting with an “aâ€, such as “a lever† and every reference to that lever thereafter is either in the form of “the lever† or “said that lever.†Therefore you can’t recite “the lever†before you provide “a lever†earlier in the claim. if the claim does recite “the lever†before any reference in the claim is made to “a lever†the examiner may reject the claim on the basis that “the lever†lacks an antecedent basis of the claim. This is just one of the formalities that are required when drafting claims. Antecedent basis issues can almost always be remedied by an amendment to the claims that introduces the element in question with an “a†or “anâ€.

Above are just some of the formality issues that might cause the examiner to issue an objection of your application.

II. Substantive Rejections

Many of the above mentioned formality objections can be easily overcome as long as the application was drafted properly in the first case. Â However dealing with substantive rejections can often be more challenging. A substantive rejection often includes an assertion by the examiner that the invention as described in the claims is not new as compared to the prior art.

There are a number of ways to overcome a rejection based on the prior art. These include amending the claims to include further limitations so that the claim language doesn’t overlap the prior art, making arguments that the examiner’s interpretation or understanding of the prior art is not correct, making arguments that the examiner has improperly combined two or more prior art references that cannot be combined under the circumstances. Other methods to overcome the office action which are less common can include proving, if the application was filed before the America Invents Act deadline, that you invented your invention before the reference date of the prior art and diligently pursued a prototype for filing a patent application.

Rejections based on novelty, i.e. that the claimed invention is not new in relation to the prior art, usually take one of two forms: a 35 USC 102 anticipation rejection, a 35 USC 103 obviousness rejection, or a 35 USC 101 ineligible subjectmatter rejection.

Section 102 Anticipation Rejection

In a section 102 anticipation rejection the examiner has to show that each and every element of the subjects claimed is found in one reference either explicitly or implicitly. So to overcome a 102 rejection the task is either to add additional limitations to your claim or to argue that the reference does not contain each and every element of your claim.

Section 103 Obviousness Rejection

In a section 103 obvious this rejection, the examiner could not find every element of your claim and one single reference instead the examiner uses two or more references combined to find every element of your invention. The examiner must put forth a basis as to why it would have been obvious to one skilled in the art related to your invention to have combined the references to meet all of the elements of claim. To overcome a 103 rejection limitations several approaches can be taken, including elements can be added to the claim which are not found in any of the references cited, arguments can be made that the references cannot be combined, an argument can be made that the references do not show all the elements as the examiner claims.

Section 101 Ineligible Subject Matter Rejection

in a section 101 rejection the examiner is asserting that one or more claims of the application are not directed to subject matter that can be patented. This often arises in cases involving computer based, biotech, and business method inventions. The scope of the types of inventions that can be protected is very broad under the U.S. Patent law. But there are some exceptions such as mathematical formulas, abstract ideas, and laws of nature. However it is possible to patent the application of a mathematical formula or abstract idea but not the mathematical formula or idea itself. If the patent application was drafted properly at the beginning it is often possible to overcome this rejection by incorporating appropriate elements into the claims or working with the wording of the claims to avoid claiming directly abstract ideas, mathematical formulas, or laws of nature.

Conclusion

While the above objections are not an exhaustive list, but comprise some of the common issues that arise during substantive examination of patent applications. Many of them can be overcome by the appropriate argument or amendment in a response depending in some cases one how the patent application was originally. A properly drafted application seeks to anticipate and provide support for any changes that might need to be made later during examination by the Patent Office.