Move, Inc. v. Real Estate Alliance Ltd., Dkt. No. 2012-1342 (Fed. Cir. March 4, 2013)

Move, Inc. v. Real Estate Alliance Ltd., Dkt. No. 2012-1342 (Fed. Cir. March 4, 2013)

Move sought declaratory judgement of non-infringement of two of Real’s patents, U.S. 5,032,989 and U.S. 4,870,576. Real counterclaimed that Move’s “Search by Map” and “Search by Zip Code” website functions infringed the patents. The district court issued summary judgement of non-infringement.

Claim 1 of the ‘989 patent was at issue on appeal and was directed to a method for locating real estate properties using a zoom enabled map on a computer. Claim 1 provided:

1. A method using a computer for locating available real estate properties comprising the steps of:

(a) creating a database of the available real estate properties;

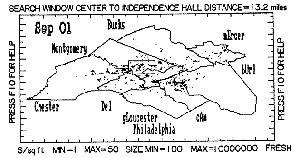

(b) displaying a map of a desired geographic area;

(c) selecting a first area having boundaries within the geographic area;

(d) zooming in on the first area of the displayed map to about the boundaries of the first area to display a higher level of detail than the displayed map;

(e) displaying the first zoomed area;

(f) selecting a second area having boundaries within the first zoomed area;

(g) displaying the second area and a plurality of points within the second area, each point representing the appropriate geographic location of an available real estate property; and

(h) identifying available real estate properties within the database which are located within the second area.

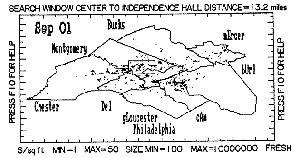

Direct Infringement. In a prior appeal the Federal circuit determined that “selecting an area” as recited in steps (c) and (f) of claim 1 meant that “the user or a computer chooses an area having boundaries, not when the computer updates certain display variables to reflect the selected area.”

The Move system allowed the user to select a predefined area, such as a city, and the system would then zoom into the map according to the predefined boundaries of the area. The court found that the system did not “select an area having boundaries” by showing the predefined area after a user selected the area. Rather the computer just retrieved the map associated with the user’s choice. Therefore Move did not directly carry out the (c) and (f) steps of the claim.

Since Move did not directly carry out all of the steps, it must have direct or control over the performance of the missing steps by another party to be liable for direct infringement. The court found that it did not exert the required direction or control over its users to be liable for direct infringement.

Indirect infringement. The Federal Circuit found that the district court did not conduct the required analysis as to whether Move could be liable for inducing infringement by inducing its users to perform the claimed steps that Move did not itself perform.

Claim Language Suggestions. To allow for direct infringement, the claims could have been worded differently. Assuming the following was supported by the specification and permissible by the prior art, step (c) could have provided “receiving from a user a selection of a first area having boundaries within the geographic area” and step (f) could have provided “receiving from a user a selection of a second area having boundaries within the first zoomed area.” Such language might provide a better case for direct infringement.

[gview file=”http://www.waltmire.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/FedCir_Move_v_Real_2012-1342.pdf”]