Clients often wonder why a patent application on a relatively simple invention is relatively long. The answer is that even the most simple inventions are not simple to describe properly in a patent application.

Clients often wonder why a patent application on a relatively simple invention is relatively long. The answer is that even the most simple inventions are not simple to describe properly in a patent application.

To write a strong patent application, the invention needs to be described to a level of detail that many clients would not have thought necessary.

Its not unusual that a client brings a 3 to 5 page provisional patent application that the client wrote themselves, and the non-provisional application I write is at least three to four times as long, or 15 to 20 pages or more.

This is why DIY patent applications are difficult to write well (but there are options and trade-offs when money is tight).

The details and length are necessary because that content lays a foundation for a potentially broad patent. That detail in the patent application should include, were possible, a description of alternative ways of making and/or using your invention.

Patent attorneys call these alternative ways of making and/or using your invention, different or alternate embodiments of the invention.

To illustrate why it is important to describe alternative ways of making and/or using your invention, we can look at the case of Tronzo v. Biomet, Inc., 156 F.3d 1154 (Fed. Cir. 1998).

Describing Only One Way of Making/Using Your Invention is Limiting

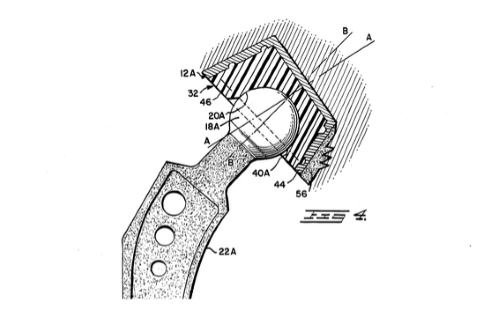

In the Trozno case, the patent owner obtained Patent 4,743,262 (the ‘262 patent) on a cup for a hip replacement device. The parent patent application of the resulting the ‘262 patent only described the cup as a “conical cup.” The patent claim did not include the conical limitation for the cup. So the patent claim was to a generic cup, without limitation to the shape of the cup.

The defendant’s device used a hemispherical cup.

So the question was whether the description of “conical cup” adequately supported the claim to a generic cup. If so, the claim would cover more than just conical cups but would cover cups of other shapes, such as the defendant’s hemispherical shaped cup. If not, the claim was not entitled to the filing date of the parent application for failing to comply with the written description requirement.

The written description requirement in patent law provides that the patent application must “contain a written description of the invention, and of the manner and process of making and using it.” Courts have said to meet the written description requirement that application must reasonably convey to one of skill in the art that the inventor possessed the claimed subject matter at the time the application was filed.

In the Trozno case, the court found that the parent application only described one shape of cup, the conical shaped cup. The patent owner’s attempt to claim the broader generic cup was overreaching beyond was described in the application. The end result was that the claims were invalid and did not cover the hemispherical cup in the product provided by the defendant.

Describe Multiple Variations of Your Invention and Its Components

How could this have been avoided? In reasoning that the ‘262 patent only covered conically shaped cups, the lower court noted that the patent application did “not attempt to identify other, equally functional shapes or talk in terms of a range of shapes.”

There you have it. The court tells you how to get broader coverage. You get broader coverage by providing a description of a number of different shaped cups in the application.

The application might have used language such as, “a cup is provided, the cup may comprise a rounded shape, a hemispherical shape, conical shape, a cylinder shape, an elliptical shape” etc. Of course, it is important to list shapes or variations that would actually work in the invention. But the point is that you want to list alternate variations of the components and aspects of the invention.

When listing the generic component “cup” along with various options for the shape of the cup, this enables you to write boarder claims. Boarder claims provide you with a stronger patent because you may be able to use broad language in your patent claims, e.g. the broad generic “cup” vs. the limited “conical cup.”

In a patent application, it is important to describe the benefits and advantages that the invention provides over the prior art. This gives the invention context and provides reasons for the Examiner to find the unique features of the invention novel and non-obvious.

In a patent application, it is important to describe the benefits and advantages that the invention provides over the prior art. This gives the invention context and provides reasons for the Examiner to find the unique features of the invention novel and non-obvious.