Classen Immunotherapies, Inc. v. BioGen IDEC, No. 2006-1634 (Fed Cir. Aug 31, 2011) [PDF].

Classen Immunotherapies, Inc. v. BioGen IDEC, No. 2006-1634 (Fed Cir. Aug 31, 2011) [PDF].

In this case the court considered the scope of patentable subject matter under 35 USC 101. While the patents-in-suit are directed toward methods of medical treatment, the scope of patent able subject matter under section 101 is often considered in computer science and business method related patents. This case raises the issue of what constitutes a purely mental process and further what constitutes a insignificant post-solution activity.

Classen sued BioGen, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Kaiser Permanente for infringement of US Patent Nos. 6,638,739, 6,420,139, and 5,723,283 (“Classen Patents”) each titled, “Method and Composition for an Early Vaccine to Protect Against Both Common Infectious Diseases and Chronic Immune Mediated Disorders or their Sequelae.†On remand from the Supreme Court, in view of Bilski v. Kappos, 130 S. Ct. 3218 (2010), the Federal Circuit considered whether the claims of the Classen Patents were in valid under 35 USC 101 as being directed to an abstract idea. The Federal Circuit found that the claimed subject matter two ( the ‘139 and ‘739 patents) of the three Classen Patents were within the scope of section 101.

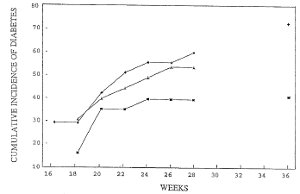

The court summarized that the Classen patents state “Dr. Classen’s thesis that the schedule of infant immunization for infectious diseases can affect the later occurrence of chronic immune-mediated disorders such as diabetes, asthma, hay fever, cancer, multiple sclerosis, and schizophrenia, and that immunization should be conducted on the schedule that presents the lowest risk with respect to such disorders. ”

Patents-in-Suit. Claim 1 of the ‘739 patent, representative of the ‘139 and ‘739 patents, provides:

1. A method of immunizing a mammalian subject which comprises:

(I) screening a plurality of immunization schedules, by

(a) identifying a first group of mammals and at least a second group of mammals, said mammals being of the same species, the first group of mammals having been immunized with one or more doses of one or more infectious disease-causing organism-associated immunogens according to a first screened immunization schedule, and the second group of mammals having been immunized with one or more doses of one or more infectious disease-causing organism-associated immunogens according to a second screened immunization schedule, each group of mammals having been immunized according to a different immunization schedule, and

(b) comparing the effectiveness of said first and second screened immunization schedules in protecting against or inducing a chronic immune-mediated disorder in said first and second groups, as a result of which one of said screened immunization schedules may be identified as a lower risk screened immunization schedule and the other of said screened schedules as a higher risk screened immunization schedule with regard to the risk of developing said chronic immune mediated disorder(s),

(II) immunizing said subject according to a subject immunization schedule, according to which at least one of said infectious disease-causing organism-associated immunogens of said lower risk schedule is administered in accordance with said lower risk screened immunization schedule, which administration is associated with a lower risk of development of said chronic immune-mediated disorder(s) than when said immunogen was administered according to said higher risk screened immunization schedule.

Claim 1 of the ‘283 patent provides: A method of determining whether an immunization schedule affects the incidence or severity of a chronic immune-mediated disorder in a treatment group of mammals, relative to a control group of mammals, which comprises immunizing mammals in the treatment group of mammals with one or more doses of one or more immunogens, according to said immunization schedule, and comparing the incidence, prevalence, frequency or severity of said chronic immune-mediated disorder or the level of a marker of such a disorder, in the treatment group, with that in the control group.

Majority. The majority noted, quoting Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175, 187 (1981), that “[i]t is now common place that an application of a law of nature or mathematical formula to a known structure or process may well be deserving of patent protection.” The court found that the ‘139 and ‘739 patents included a physical step of immunization, and therefore was not a purely mental method. The court found with the immunization step the claims were directed to a specific tangible application under Bilski v. Kappos. In upholding the validity of the claims of the ‘139 and ‘739 patents, the court did not find that the immunization step was an “insignificant postsolution activity” under Diehr.

However, the court characterized claim 1 of the ‘283 patent as covering the idea of collecting and comparing known information. The court characterized the “immunizing” in the ‘283 patent as referring to the gathering of published data and therefore not a further act to set apart the claims from the abstract principle that a variation in immunization schedules may have consequences for certain diseases. As a result, the court found the claims of the ‘283 patent were invalid under section 101 as being directed to an abstract idea.

Additional View of Chief Judge Rader. Judge Rader wrote separately to comment on “significant unintended implications” of the patent eligibility doctrine under section 101. One implication is that creative claim drafting can be employed to avoid subject matter exclusions under section 101, such as the Beauregard claim for “computer programs embodied in a tangible medium” rather than computer programs themselves to avoid being rejected as a mathematical algorithm. Another implication was that subject matter limitations increase the expense and difficulty in obtaining a patent and may frustrate innovation and drive research funding to other “more hospitable locations” (countries). Judge Rader seems to encourage litigants to focus on novelty and adequate disclosure rather than whether the subject matter should be excluded under section 101 from patentability.

Dissent. The dissent would have held all the claims in question invalid as an unpatentable abstract idea. The dissent asserted that there was no difference, for section 101 purposes, between the claims of th2 ‘283 patent and the claims of the ‘139 and ‘739 patents, all of which require two steps according to the dissent: “(1) compare the incidence of chronic immune mediated disease in two groups of mammals who were immunized according to different schedules and then (2) immunize a mammal according to the lower risk schedule.” The dissent stated that the ‘283 patent claims “the scientific method as applied to the field of immunization.” The dissent said the ” claims do nothing more than suggest that two immunized groups be compared to determine which one is better” and therefore are “exactly the type of ‘abstract intellectual concepts that ‘are the basic tools of scientific and technological work.’ (citing Gottschalk v. Benson, 409 U.S. 63, 67 (1972)). The dissent provides one absurd example of liability under the patents-in-suit, “[a] patient might be liable for joint infringement by receiving an immunization, and then wondering why their friend got sick when he got the same immunization.”

Conclusion. This case is favorable for clients seeking patent coverage in computer science, business methods, and related fields as it takes broad view of patentable subject matter.

Privacash, Inc. v. Am. Express Co., No. 2011-1027 (Aug. 11, 2011) [PDF].

Privacash, Inc. v. Am. Express Co., No. 2011-1027 (Aug. 11, 2011) [PDF].