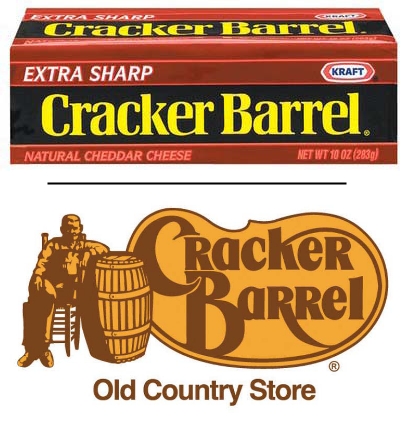

The Cracker Barrel Old Country Store (CBOCS) is a well known chain of restaurants. Kraft is a well-known manufacturer of food products sold in grocery stores, including a variety of packaged cheeses. Some of the packaged cheeses are sold under the trademark “Cracker Barrel.” Kraft sued CBOCS when it discovered that CBOCS planned to sell food products, such as packaged hams, in grocery stores under its logo, “Cracker Barrel Old Country Store.” Kraft Foods v. Cracker Barrel Old Country Store, No. 13-2559 (7th Cir. 2013).

The Cracker Barrel Old Country Store (CBOCS) is a well known chain of restaurants. Kraft is a well-known manufacturer of food products sold in grocery stores, including a variety of packaged cheeses. Some of the packaged cheeses are sold under the trademark “Cracker Barrel.” Kraft sued CBOCS when it discovered that CBOCS planned to sell food products, such as packaged hams, in grocery stores under its logo, “Cracker Barrel Old Country Store.” Kraft Foods v. Cracker Barrel Old Country Store, No. 13-2559 (7th Cir. 2013).

Kraft objected only to the sale of products under the mark “Cracker Barrel Old Country Store” in grocery stores. It did not object to the sale of such products in the CBOCS restaurants or online. The district court granted a preliminary injunction prohibiting CBOCS from selling food products under the Cracker Barrel Old Country Store mark in grocery stores. The Seventh Circuit Appeals court agreed and upheld the injunction.

The 7th Circuit strongly questioned the usefulness of surveys in trademark lawsuits. Generally in a trademark dispute the question is whether there is a likelihood that the consumer would be confused to believe that the product/service of the junior user originates from the same source as the senior user’s product/service. One piece of evidence that a party may put forth is a survey of relevant consumers for showing whether confusion is likely.

Expensive Surveys

The problem with survey’s, aside from the issues identified by the Court, is that they can be expensive. An expert must be hired. The expert must plan a survey relevant to the case. The survey must be conducted. Then the expert must prepare a report with conclusions from the survey. Then the other party has the right to depose and otherwise attack the survey and its conclusions. All of the expert cost associated with surveys can total from $20,000 to over six figures depending on the case.

The Opportunity to Forgo Surveying

The court’s negative view of the value of surveys, as explained below, is helpful for litigants with limited budgets. If a litigant can dispense with the need to conduct surveys, the litigant can reduce costs substantially. Yet, forgoing evidence that could be supportive of the party’s position is always a risk. However, a party may decide to forgo a survey, particularly in the 7th Circuit in view of this Kraft Foods case.

General Problems with Surveys

The court started off with an overview of the problems with relying on surveys in trademark cases. The court stated that “Consumer surveys conducted by party-hired expert witness are prone to bias.” Citing several academic articles, the court continued, “There is such a wide choice of survey designs, none foolproof, involving such issues as sample selection and size, presentation of the allegedly confusing products to the consumers involved in the survey, and phrasing of questions in a way that is intended to elicit the surveyor’s desired response– confusion or lack thereof–from the survey respondents.”

Further referring to the academic articles, the court stated, “Among the problems identified by the academic literature are the following: when a consumers is a survey respondent, this changes the normal environment in which he or she encounters, compares, and reacts to trademarks; a survey that produces results contrary to the interest of the party that sponsored the survey may be suppressed and thus never become a part of the trial record; and the expert witnesses who conduct surveys in aid of litigation are likely to be biased in favor of the party that hired and is paying them, usually generously.”

The court concluded that generally, “All too often experts abandon objectivity and become advocates for the side that hired them.” This makes logical sense. A party will not hire an expert to give them a conclusion that damages the party’s position.

Professional Expert Witnesses

Turing the the survey in the Kraft Foods case, the court noted that Kraft’s Expert, Mr. Poret, appeared to be “a professional expert witness.” The court said that it would not hold this against him. However noting that Poret appears to be a professional expert witness implies a negative connotation. This appears especially evident when read in context with the court’s citation to academic literature to support the proposition that too often become advocates for the side that hired them.

Kraft Survey Problems

The Poret survey was conducted online via email. Poret emailed photos of CBOCS sliced spiral hams to 300 american consumer of whole-ham products and then asked in the email whether the company that makes ham also makes other products, and if so what products. About a quarter of the respondents said the company makes cheese. However the court was not convinced by this result noting that consumers could have guessed that the company makes other products because many companies have multiple product lines. Then the consumer could have guessed that the company made cheese.

Next, Poret showed “a control group of 100 respondents essentially the same ham, but made by Smithfield–and none of these respondents said that Smithfield also makes cheese.” The court noted that “Poret inferred that the name ‘Cracker Barrel’ on the ham shown to the 300 respondents had triggered their recollection of Cracker Barrel cheese, rather than the word ‘ham’ being the trigger.” The court found that the relevance of this conclusion was obscure. The court stated, “Kraft’s concern is not that people will think that Cracker Barrel cheeses are made by CBOCS but that they will think that CBOCS ham is made by Kraft, in which event if they have a bad experience with the ham they’ll blame Kraft.”

Validity of Online Surveys Questioned

Also the court question the validity of online surveys when drawing conclusions about products purchased in person in a store. The court said, “it’s very difficult to compare people’s reactions to photographs shown to them online by a survey company to their reactions to products they are looking at in a grocery store and trying to decide whether to buy.” The court continued, “The contexts are radically different, and the stakes much higher when actual shopping decisions have to be made (because that means parting with money), which may influence responses.” Online surveys are less expensive than in-person in-store surveys. However, this opinion counsels away from using online surveys when the products at issue are purchased in-person in a retail location.

Side-by-Side Statististical Sales Data Also Questioned

The court proposed using statistical sales data as an alternative to a survey. But then concluded that such statistical sales data would likely lack reliability necessary to support a basis to refuse “granting preliminary injunctions in trademark cases.” The proposed statistical data process would involve analyzing the actual sales of the two products at issue in the real world. “…in some of [the stores] Kraft Cracker Barrel cheese would have been displayed side by side with CBOCS hams plus similar meat products sold at comparable prices, while in other stores the cheese and hams would have been displayed in different areas of the store, and still other grocery stores would have carried CBOCS hams but not Kraft Cracker Barrel cheese.” The court stated that by examining the greater sales, if any, that “CBOCS hams obtained by proximity to the Kraft Cracker Barrel label, an expert witness might be able to estimate the extent of consumer confusion.” The greater boost in sales in those CBOCS hams in proximity to the Kraft Cracker Barrel cheese, the greater likely association of the CBOCS hams with the marker of the Cracker Barrel cheese. Still the court discounted this method in this scenario, stating, “nor have we such confidence in the reliability of such a study that we would think it an adequate basis for refusing to grant preliminary injunctions in trademark cases.”

Expert Testimony on Buying Habits And Consumer Psychology Suggested

There was one type of evidence that court would consider. The court noted that testimony of “experts on retail food products about the buying habits and psychology of consumers of inexpensive food products” would be illuminating in trademark cases. The court cited an academic article providing that “neither courts nor commentators have made any serious attempt to develop a framework for understanding the conditions that may affect the attention that can be expected to be given to a particular purchase.”

Conclusion

The courts criticism of trademark surveys is a benefit to litigants on a limited budget. While forgoing potentially favorable survey evidence is a risk, the opinion in this case provides authority for calling into question the other party’s survey conclusions.