It can be difficult to write an accurate and complete description (identification) of goods/services in a federal trademark application. When describing the goods and services you are or want to sell/provide, you want use somewhat broad language, but not too broad.

You cannot broaden the identification after the application is filed. In some cases, if the description is not accurate and the needed changes would broaden the identification, the application may be lost without a refund. However, if the description is too narrow, you could give up valuable trademark protection that you could otherwise obtain.

So how do you draft a description that is just right? I’ll explain that below, but first, why does the application require a description of goods/services?

Why Do I need a Description Of Goods/Services?

Except for famous trademarks, trademarks rights generally do not extend to protect every product or service. If you use the trademark ACME for selling tooth brushes only, you can not use trademark law to stop someone from using ACME for selling sailing yachts. Consumers don’t expect that providers of tooth brushes also sell yachts.

Trademark rights extend to cover instances another uses your mark or something similar with goods/service that are the same or similar to goods/services as you provide under the mark. Therefore, the scope of trademark protection depends on the goods and/or service that you provide under the mark.

In order to let the public know the scope of your trademark rights based on the goods/services, the USPTO requires that you provide a description of the goods and/or services that the mark is or will be used on or with. The USPTO calls the description of goods/service the identification of goods/services.

How does the USPTO use the Description (Why is it Important)?

The description is important because it is what the USPTO will use to compare to other trademark registrations or trademark applications to determine whether there is a conflict. The comparisons occur in two types of situations.

The first comparison situation occurs when the USPTO reviews your application. There, the USPTO compares your mark to previously filed applications and registrations that are live. If the description is too broad, then the USPTO might find a conflict between your mark and a previous application or registration, which would not have occurred if your identification was not over broad. This problem can sometimes be corrected by an amendment to the identification that narrows that identification to avoid similarities with the prior application or registration that the USPTO asserts is in conflict.

The second comparison situation occurs when the USPTO is examining later filed trademark applications. If your description is too narrow then the USTPO might allow a later filed trademark application to be registered. But if your application had a proper description the USPTO would have blocked a later confusingly similar mark from being registered. Therefore, a description that is too narrow will not properly operate to block later filed trademark applications that would otherwise be in conflict. As a result, a narrow identification of goods and services will necessarily narrow the blocking effect of your application and narrow your trademark rights.

Now you know why an description is needed and what it is for. Next, we’ll see how to draft one.

List Your Goods and/or Services

Before selecting or writing a description of goods or services, start by making a list. The list should include all of the goods and services that you sell or provide (or intend to sell or provide) under the mark. If you are already using the mark, look at your product list, your advertising, and your website, among other areas, to complete this list. If you are not already using the mark, look at your business plan or product/service plan to identify the goods and services that you will provide under this mark.

You got Lucky: Selecting a Description from the ID ManualÂ

Now see if you got lucky. What do I mean? The USPTO provides a listing of pre-approved descriptions, which are found in the US Acceptable Identification of Goods and Service Manual (a.k.a the ID Manual). If you find a description(es) provided in the ID Manual that accurately and completely describes the goods and/or services that you provide or intend to provide, then you can select it and you’re done.

If you choose a description from the ID Manual the USPTO will not object to it. The USPTO charges lower fees for an application (TEAS PLUS form application) where the description(s) are selected from the ID Manual. Why? Because the trademark examining attorney will not need to review that part of your application, because the description is already pre-approved. Less work for the USPTO, less government fees.

However, many situations are not accurately or completely covered by a pre-approved description in the ID Manual. Many of trademark applications that I file require a custom written description because the ID Manaul does not completely and accurately describe all of my client’s goods / services. And if that’s true for your case, choosing a description that is “close” but not correct or complete is a problem. Such a “close” selection may result in the USPTO rejecting your trademark application, or if registered, a registration that is unnecessarily narrow, or one that is subject to cancelation as inaccurate.

If you can’t find accurate and complete descriptions in the ID Manual don’t try to force it by selecting the closest option. You’re going to have to do the hard work of writing a description.

Doing the Hard Work: Drafting an Identification of Good / Services

In some cases, writing your own description can be one of the most difficult parts of a trademark application to complete correctly. Here are some pointers that you should know.

Use a Portion from the ID Manual, if Possible

Even if the ID Manual does not have the exact description you need, it might have a portion of a description that you could use. You might take that useful portion and modify it and/or add to it to provide an accurate and/or complete description.

Do Not Merely Repeat the Class Heading

For each description you will need to select a corresponding international trademark class (“trademark classes”), which I explain below. Your description cannot merely repeat the class heading or title of classes of goods and/or services.

For example, class 25 has a heading or title of “Clothing, footwear, headgear. Providing a description of “clothing” is merely repeating a portion of the class heading, and would not be accepted. Instead more detail is needed, e.g. “clothing, namely, t-shirts, pants, and gloves.”

Similarly, computer software must be described with particularity. It is not sufficient to provide a description of “computer software.” The description of computer software should include the function or purpose. The description “computer game software” provides a purpose or field of use of “gaming.” Searching the ID Manual for “computer hardware” shows many examples: “computer hardware and software for setting up and configuring wide area networks”, “Computer operating software”, “Computer software platforms for {indicate function or use},” among many others.

Avoid Open Indefinite Words Leading A List

Avoid indefinite words and phrases, such as “including,†“comprising,†“such as,†“and the like,†“and similar goods,†“like servicesâ€, “etc.” Instead, you can use a broad term followed by the terms “namely,” “consisting of,†“particularly,†to list a specific set of goods or services within a broader term where more particularity is needed, e.g. “power tools, namely, drills” or “needle point kits consisting of needles, thread, and patterns” or “projectors, particularly projectors for the entertainment industry.”

Don’t Use Unqualified Broad Terminology if it would Fall Into Multiple Classes

The USPTO will object if the broad terminology used in the description would fall into multiple trademark classes. For example, an description of “blankets†would not be accepted without qualifying wording. “Blankets” fall into multiple classes. e.g., fire blankets (class 9), electric blankets (class 11), horse blankets (class 18), and bed blankets (class 24).

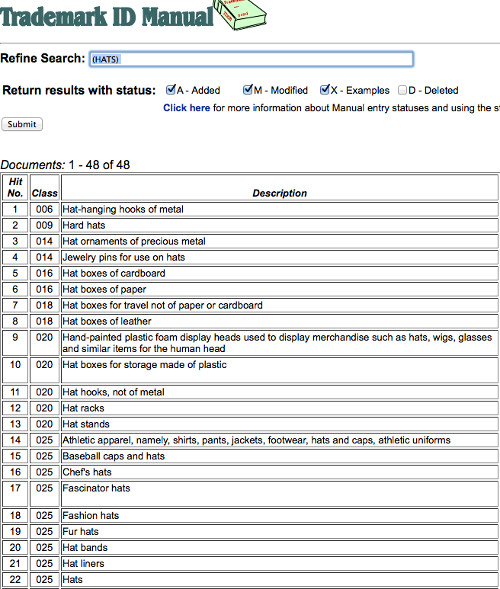

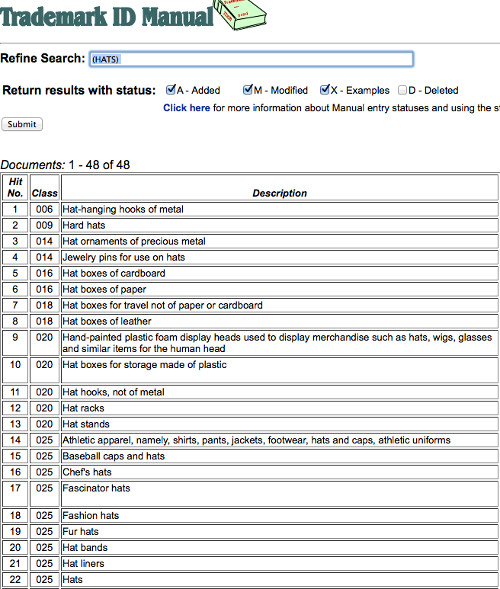

To avoid using terminology that falls into multiple classes, search the ID Manual for the terminology you are considering using in the description. If the results show that terminology falls in more than one class, then you know you need more specific wording or you need to use different terminology that does not fall into multiple classes. Click the thumbnail image at the left of this paragraph to see a screenview of a search of the ID manual for “blanket”. In that screenview you can see under the “class” column there are results in classes 9, 10, 11, 16, 17, 18, 22, 24, 25, 29, 30, 36, 39, and 43. So, the term “blanket” alone is too broad.

To avoid using terminology that falls into multiple classes, search the ID Manual for the terminology you are considering using in the description. If the results show that terminology falls in more than one class, then you know you need more specific wording or you need to use different terminology that does not fall into multiple classes. Click the thumbnail image at the left of this paragraph to see a screenview of a search of the ID manual for “blanket”. In that screenview you can see under the “class” column there are results in classes 9, 10, 11, 16, 17, 18, 22, 24, 25, 29, 30, 36, 39, and 43. So, the term “blanket” alone is too broad.

Use Language Understandable to the Average Person

The language used in the identification should be that which could be understood by the average person, not having an in-depth knowledge of the relevant field. If terms of art of a particular field or industry are used in the description and those terms are not understood by the general population, the identification should include an explanation of the specialized terminology.

Use Proper Punctuation (Semicolon vs. Comma)

The use of a comma instead of a semicolon can be problematic. A semicolon should be used to separate distinct categories of goods or services within a single class. For example, in the case of In re Midwest Gaming & Entertainment LLC, No. 85/111552 (TTAB 2013), the prior registrant’s use of a semicolon rather than a comma in the description of services was key to the USPTO providing that registration with a broad blocking effect. In that case, the applicant applied to register the mark LOTUS for “bar services located in a casino.” The trademark board affirmed the trademark examining attorney’s refusal to register that mark based on a previously registered trademark LOTUS (Reg. No. 3,398,674) for “providing banquet and social function facilities for special occasions; restaurant and bar services.”

The applicant argued that “restaurant and bar services” should be limited by the preceding language of “providing banquet and social function facilities for special occasions.” Particularly, the applicant argued that the restaurant and bar services of the registration, “must be limited to a specific type of such services and to a specific trade channel and class of purchasers, i.e., to restaurant and bar services provided in connection with ‘providing banquet and social function facilities for special occasions.’â€

The trademark board rejected this argument, stating “Under standard examination practice, a semicolon is used to separate distinct categories of goods or services.” The board continued, “We find that here, the semicolon separates the registrant’s ‘restaurant and bar services’ into a discrete category of services which is not connected to nor dependent on the ‘providing banquet and social function facilities for special occasions’ services set out on the other side of the semicolon.”

As the registrant’s “restaurant and bar services” were not limited to any particular location or trade channel, then it was presumed to cover all trade channels or classes of purchasers, including those in a casino. In other words, the registration’s broad use of “restaurant and bar services” stood on its own, separate from and not limited by “banquet and social function facilities” services. The use of a semi colon provided the owner of the registered LOTUS mark with broad blocking protection.

If a comma was used rather than a semi colon here, the result of this case would have been different. The LOTUS registration would not have blocked the LOTUS applicant. The use of a comma, when a semi colon should be used, would have narrow the blocking effect of the LOTUS registered trademark. A narrowed blocking effect means that similar marks will be more likely to be registered and your ability to broadly protect your trademark rights will be reduced.

Do not include trademarks in the Description

Do not include trademarks in your description. If your product is designed to work with a particular other product, describe that other product generally rather than referring to it by its brand name. Not: “engine parts for use on Ford cars”, but instead “engine parts for use on automobiles.”

Do not include goods or services that you do not sell to the public

If you use marketing to promote your business (like most businesses), but you do not help others market their business, non-profits, etc., then you should not list marketing in your description of services. The description includes goods and/or services that you sell to or provide for others.

Reviewing other Registrations in the Field

In the same way that searching for descriptions from the ID Manual can give you ideas about how to write a description, so too can searching the descriptions provided in trademark registrations in the same field as you operate. Reviewing descriptions in issued trademark registrations can help you determine if you have missed anything in your description. However, it is always possible that such registrations could be unduly narrow or incorrect. Therefore you should look at number of registrations to get a better feel for whether one particular description is an outlier. And you should never use a description just because it is found in a registration if it does not accurately and completely reflect the goods or services you provide or intend to provide. Looking at other registrations is just a way to get ideas. But not every referenced registration will provide good information applicable to your situation. And sometimes there are no good examples, or at least not ones that are easily found, for a particular product or service.

The USPTO provides a first video and a second video that further discuss the identification of goods and services. And, section 1402 of the Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure (TMEP) provides additional information on the requirements for a proper identification of goods and services.

Why do I need to Select Class(es) of Goods and Services?

In addition to writing a description, the USPTO requires you to select one or more international trademark classes of goods and services from the Schedule of International Trademark Classes of Goods and Services (Schedule) that correspond to the goods and services provided in the description portion explained above. This step seems repetitive. If you already have a description of goods and services, why do you have to select one or more classes that this description falls into?

The answer is: so that the USPTO can determine how much money to charge you for the application. The Schedule divides all of the goods and services into 45 different classes.

The trademark classification system is an administrative system where the government determines how much work it will be to process your application and charges you filing fees accordingly. If you provide a description that covers many classes, then the USPTO will have to search a larger volume of prior trademark registrations and applications to determine whether your mark conflicts with any previous trademark registrations and applications.

For example, if you are going to use your mark ACME for the goods of toothbrushes, bath towels, and t-shirts, the USPTO will need to search for prior registrations and applications that claim use of ACME (or similar marks) on all of those goods and similar goods. But if you only claim the use of ACME for the sale of toothbrushes, then USPTO will have less work to search for the use of ACME (or similar marks) for just toothbrushes and similar goods. Not needing to search for mark used with bath towels and t-shirts, means its less work for the USPTO. There are less marks to search through when an application claims fewer goods or services.

Selecting the Right Class(es) of Goods and Services

You can read the description provided for each class here and select the appropriate one or more classes. Another way to determine which class(es) you should designate in your trademark application is to look at the classes provided for the same or similar goods or services provided in the ID Manual. For example, if you are going to sell HATS and you search the ID Manual for HATS. An excerpt of the results is shown below:

If you sell Hard Hats then you would select class 9. If you are selling general use hats then you would select class 25.

Also as explained above regarding the description, you can search existing trademark registrations in your field to see what classes others have selected for your type of goods and services.

Technology Fields

Certain technologies can span across multiple classes. For example, if you provide downloadable trading software for the finance industry, such as software downloadable via a website  or through an app store, then you are providing software as goods. In that case, your application would include class 9, and may have a description of goods of: “Computer programs and computer software for electronically trading securities. ”

If instead you provide the trading software as software as a service (SaaS) available through a web interface, then instead of providing goods, you are providing services. In that case the correct class will not be class 9, but will be class 36. Class 36 covers financial services. An appropriate description might be “Securities trading and investing services for others via the internet.” If you provide a downloadable app as well as online trading then your application could include both class 9 and class 36.

In some cases, more than two classes might be needed for the broadest protection in the case that the technology component does not fit within the industry class. For example, if your services involve telecommunications, telecommunications consulting is in class 38 and telecommunications technology consulting is in class 42.

Conclusion

Sometimes providing an appropriate description of the goods and/or services and selecting the right is easy, e.g. hats. In many other cases, it is hard. Yet, providing an accurate and complete description of goods / services in one of the most important components of a trademark application. The description determines (1) whether your application will conflict with a prior registration or application, and (2) the extent to which your registration will act to block later filers from registration on similar marks. In short, the description and class selection impacts the scope of your trademark protection at the USPTO.

Lead image credit to USPTO here.

Daniel Group obtained a federal registration on service mark “ServicePerformance.” But Daniel Group failed when it demanded and then sued claiming trademark infringement to stop Service Performance Group from using that name for similar services. Why did it fail?

Daniel Group obtained a federal registration on service mark “ServicePerformance.” But Daniel Group failed when it demanded and then sued claiming trademark infringement to stop Service Performance Group from using that name for similar services. Why did it fail?

What if your service business has a location only in one state? What if your business sells goods only in one state? Do such business have the opportunity to obtain a federal trademark application?

What if your service business has a location only in one state? What if your business sells goods only in one state? Do such business have the opportunity to obtain a federal trademark application? The date that you first used your trademark could be, but probably is not, the correct date to use as the first use in commerce date in a federal trademark application. Why? Because in many cases the first use of the trademark was on a website or marketing material before an actual sale or shipment of the goods or rendering of the service.

The date that you first used your trademark could be, but probably is not, the correct date to use as the first use in commerce date in a federal trademark application. Why? Because in many cases the first use of the trademark was on a website or marketing material before an actual sale or shipment of the goods or rendering of the service.

Filing a federal trademark application online looks easy. Just fill in the blanks in

Filing a federal trademark application online looks easy. Just fill in the blanks in

A client arrives at your law office and wants to start a company and form a corporation or LLC. Your client had a company name in mind. You search the Secretary of State records for other companies with the same or similar name and find nothing. You also search the state trademark database and find nothing. You prepare an engagement agreement for the work of forming the corporation. Is your client in the clear to use the name? Not necessarily.

A client arrives at your law office and wants to start a company and form a corporation or LLC. Your client had a company name in mind. You search the Secretary of State records for other companies with the same or similar name and find nothing. You also search the state trademark database and find nothing. You prepare an engagement agreement for the work of forming the corporation. Is your client in the clear to use the name? Not necessarily.