“…each coowner [of a patent] is ‘at the mercy’ of its other co-owners.” – Federal Circuit Court of Appeals.

STC.UNM (the licensing arm of University of New Mexico) was at the mercy of Sandia Corp. regarding STC’s patent.

STC sued Intel Corporation for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 6,042,998 (the ‘998 patent) in the case of STC.UNM v. Intel Corp., No. 2013-1241 (Fed. Cir. 2014). STC and Sandia co-owned the ‘998 patent.

But, Sandia refused to join the lawsuit against Intel, “prefer[ring] to take a neutral position with respect to this matter.” This led the court to dismiss the infringement suit against Intel.

STC was at the mercy of Sandia’s refusal to join the lawsuit. Maybe this lawsuit against Intel could have resulted a large money judgement for STC. But, Sandia’s neutrality was the end of STC’s enforcement of ‘998 patent was against Intel.

All Patent Co-Owners Must Join A Patent Infringement Suit

“[A]ll coowners must ordinarily consent to join as plaintiffs in an infringement suit,” the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals said. “[O]ne co-owner has the right to impede the other co-owner’s ability to sue infringers by refusing to voluntarily join in such a suit.”

You may say this is not fair. If I’m an owner of a patent, why can’t I sue without the other co-owners?

The court says, “rule requiring in general the participation of all coowners safeguards against the possibility that each coowner would subject an accused infringer to a different infringement suit on the same patent.” In other words, the rule guards against Intel first being sued by STC and then being separately sued by Sandia on the same patent.

Why not just force co-owners to be involuntarily joined to the lawsuit? The court says allowing co-owners to refuse to join a lawsuit “protects, inter alia, a co-owner’s right to not be thrust into costly litigation where its patent is subject to potential invalidation.”

Do you want to be at the mercy of a coowner?

Co-Owners Can Exploit the Patent without Consent or Dividing of Profits

Not only can a co-owner thwart enforcement attempts of a coowner, but a joint owner of a patent can exploit the patented invention in the US without consent or accounting to the other joint owners.

In particular 35 U.S.C. 262 provides, “In the absence of any agreement to the contrary, each of the joint owners of a patent may make, use, offer to sell, or sell the patented invention within the United States, or import the patented invention into the United States, without the consent of and without accounting to the other owners.”

The Problems of Prospecting Without All Patent Co-Owners

The practical impact of section 262 is that if there is a falling out or disagreement between the joint owners, it will be very difficult any of the owners of the patent to license or obtain any benefit from the patent.

Let’s say that the joint owners of the patent are Adam and Bob. If the plan is to license the invention and not make and sell it, then Adam will have a difficult time finding a company to license the invention from Adam, when Bob is not a party to the license. The company will know that it will not have exclusive rights in the invention because Bob could license to the company’s competitors. Non-exclusive licenses are generally less valuable than exclusive licenses owing to the licensee’s need to compete with other licensees. Therefore, at the very least, Adam will not be able to obtain as favorable terms as would be the case if Bob was also involved.

Further, a sales approach of one owner without the other co-owner will be more difficult. A patent savvy potential licensee will inquire as to whether joint owner, Bob, will be a party to the license. And if not, the patent savvy potential licensee may inquire why joint owner Bob is not involved and what were the circumstances of the falling out between Adam and Bob. Then Adam may be in a difficult position of explaining the dirty laundry of the situation between Adam and Bob. And if the explanation is not sufficiently satisfactory, the potential licensee may be concerned that the license will get the licensee in the middle of a dispute between Adam and Bob. Coming to the table with less than all of the joint patent owners may be a deterrent to successful licensing of the patent.

The potential licensee will also be concerned over Adam’s inability to stop third party infringers even if Bob does no licensing or selling of the patented invention. This is because of the requirement, discussed above, that all joint owners of a patent are necessary parties to patent infringement litigation and patent litigation can’t proceed without all necessary parties.

Even a cease and desist or license demand letter short of litigation will be less effective if all patent owners are not on board with enforcement. The Federal Circuit recognized this stating, “Admittedly, a license demand may have less bite if STC cannot sue potential licensees if they refuse….”

Problems Going to Market Alone

In the case where either or both Adam and Bob want to be in the business of selling the patented invention themselves and not licensing, if both Adam and Bob are in the market, Adam will have to compete will Bob and vice versa. Even if only Adam is selling in the marketplace, Adam will be unable to stop infringing competitors if Bob refuses to join in any patent lawsuit/enforcement. If Bob refuses to join in the patent enforcement efforts, the patent is essentially worthless for stopping competitors, except as a scarecrow.

Agreement Options

As you can see there are many downsides to joint ownership of a patent under the default rule provided by section 262. So, I’ll list and discuss a number of possible alternative arrangements.

- One Sided. One party owns all the jointly developed subject matter, and the other party:

- has no rights in it,

- has restricted rights, e.g. can only purchase the subject matter from the owning party, or

- has permissive rights, e.g. has a license to the jointly develop subject matter and can go to third parties and permit them make or purchase the subject matter;

- Joint Ownership. The parties jointly own the jointly developed subject matter and:

- Exclusive Marriage – Work together exclusively regarding the protection and exploitation of the subject matter, and the enforcement and licensing of related IP,

- Free For All / Hands Off – Each party can do whatever they want with the jointly owned Patent related to subject matter without accounting, agreement, or interference of the other (this is the same effect as Section 262), or

- Somewhere in between 2(A) and 2(B); or,

- New entity. The parties form a new legal entity for owning and exploiting the IP. Each party controls the new entity according to the new entity’s operating agreement.

1(A) – One Sided, No Rights – If one party owns all the rights and the other party has no rights, this is commonly a consulting situation. One party hires the other party to develop the subject matter. The hiring party pays the other party money. And the hiring party owns all the rights in the subject matter developed by the other. This is common when hiring consultants, such as developers, engineers, and other professional service providers.

This arrangement is not commonly thought of as joint development, but rather a consulting engagement, although in many cases joint development will occur because both the hiring party and the hired party will contribute to the conception and development of the subject matter. The agreement between the parties will have an assignment provision providing that the hiring party will own all the developments of the hired party. Here is a very simple example of assignment statement:

Consultant hereby assigns all right, title, and interest to the Owner in (a) the Work Product and (b) all intellectual property rights in the Work Product.

1(B) – One Sided, Some Rights – The next option is that one party owns all the rights and the other party has certain restricted rights (via a non-exclusive license) in the jointly developed subject matter. Such restricted licensed rights could include the right of the non-owning party to make, sell, and/or use the products/services embodying the jointly developed subject matter. Such rights could also include the right to purchase or use the products/services embodying the jointly developed subject matter from the owning party at a preferred or discounted price. Here is an example:

Party A (Owner) grants Party B an irrevocable, perpetual, worldwide, royalty-free non-exclusive license to [list the rights, such as: use, make, offer for sale, sell, and import ] the Work Product (“Licensed Rights”). Party B has no right to sub-license any of the Licensed Rights.

Generally these restricted rights do not include the right to sublicense, e.g. allow third parties to make, use, or sell the jointly developed subject matter. If the non-owning party has an unrestricted right to sub-license, then the non-owning party can subvert the patent enforcement efforts of the owning party by granting a targeted infringer a license without the owning party’s consent. So while the owning party can sue without the licensee’s consent or participation, if the infringer can discover the licensee’s right to sublicense and convince the licensee to grant a sublicense, the licensee can subvert the owner’s ability to obtain ongoing royalties/damages and a injunction.

1(C) – One Sided, Generous Rights – The next option is that one party owns all of the rights and the other party has generous rights in the jointly developed subject matter. If such generous rights include the ability to sublicense, then you may run into the problems just described in section 1(B). Nonetheless, since one party owns all of the jointly developed, that party does not need permission from the other to sue third parties.

2(A) – Joint Ownership, Exclusive Marriage – Under the joint ownership, exclusive marriage agreement, each party jointly owns all of the jointly developed subject matter and contractually agrees to work exclusively with each other in the development, commercialization of the jointly developed subject matter as well in the procurement and procurement of intellectual property rights in the jointly developed subject matter. The parties may agree that one of the parties will exclusively manufacture the products and the other party will exclusively purchase the product from the manufacturing party. The parties may agree that they will share equally in the cost of procurement and enforcement of intellectual property rights in the jointly developed property.

In the exclusive marriage arrangement, it will be critical that the agreement provide procedures to deal with circumstances where one party no longer wants to (1) contribute to the costs of procurement or enforcement of the intellectual property rights, (2) purchase the jointly developed product from the party manufacturing it, if any, (3) sell the jointly developed product, or (4) otherwise work with the other party.

In the case of a breakup of the parties, the agreement could provide that the party no longer wanting to contribute to the procurement or enforcement cost must assign all of that parties rights in the IP to the other party. The agreement could provide that assignment must happen without further consideration, or it could provide that the assignment party must be compensated in some manner at the time of assignment. If the assigning party must be compensated, it would be best to define the amount or a formula or determining the compensation upfront, otherwise the split could lead to litigation over the assignment/compensation, such that the IP rights can’t be enforced or properly procured during the pending litigation or dispute.

Another factor that is critical in the joint ownership arrangement, is to define each parties preexisting products and/or intellectual property. This is particularly important were each party will build on their prior products or intellectual property or will otherwise contribute some of their preexisting products or IP to the jointly developed subject matter. Therefore, the agreement should particularly define, the preexisting products or IP of each party, which are anticipated to be used or incorporated into the jointly developed subject matter.

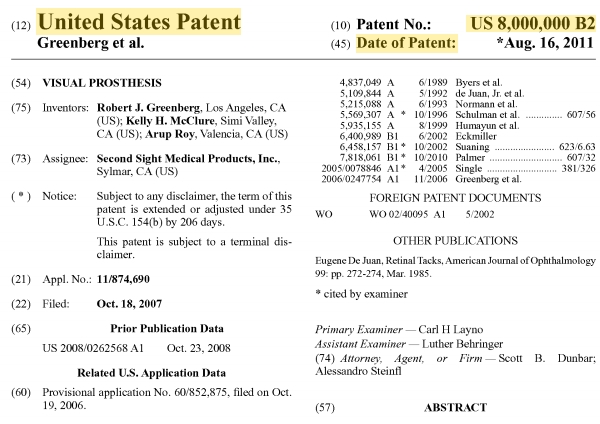

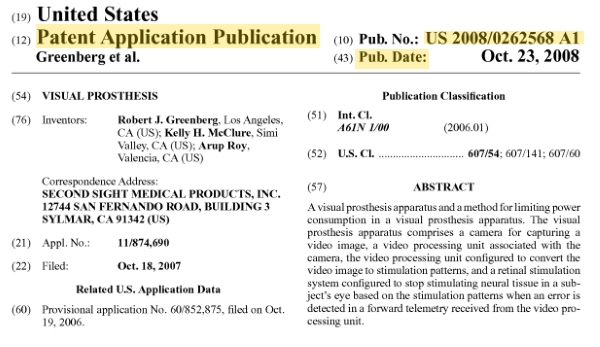

Then the agreement should make clear, unless the parties intend otherwise, that each party retains their ownership rights in their respective preexisting products/IP. Therefore preexisting products/IP should be described or referenced in the agreement. The description of the preexisting products/inventions of the parties may be provided in the form of reference to a publicly available patent(s) or patent application(s), or by attaching technical descriptions and drawings to the agreement. When attaching technical descriptions and drawings, it is important to be clear as to the scope of what is covered. As in a patent application, the parties may want to broadly describe the prior products/inventions so as not to limit their preexisting rights, to the extent possible or desired. The strategy in each individual case will depend on the circumstances.

2(B) – Free For All / Hands Off. When jointly developed subject matter is developed under an agreement that does not provide what rights each party has in the jointly developed subject matter, then with respect to patented inventions the default rule of 35 U.S.C. 262 will apply, with the attendant down sides discussed above. This might be called the free-for-all or hands-off approach.

However, note that section 262 applies to join owners of a patent. If the subject matter jointly developed is not eligible for patenting, then it would not apply. Further, even if the subject matter jointly developed is patentable, but a patent application is not filed, it may be doubtful that section 262 applies. If section 262 does not apply, then some other law would control the ownership and use of the jointly developed subject matter. Therefore, it is best to define the ownership and exploitation rules in a joint development agreement rather than relying on section 262–if you did prefer its provisions–to account for handling subject matter to which section 262 does not apply.

2(C) – Middle Ground

As is obvious, a jointed development agreement can be crafted somewhere in between an extremes of an exclusive marriage and a free-for-all.

3 – New Entity

Instead of one party or both parties owning the jointly developed subject matter, neither party can directly own the jointly subject matter. The parties can achieve this by forming a new entity (LLC, Corporation, partnership, etc.) and then can assign each of their respective rights in the jointly developed subject matter to the new entity.

Each party can own the new entity and the new entity’s operating documents can define how the parties will contribute to the development and exploitation of the jointly developed subject mater and related intellectual property. The operating agreement will also define how numerous situations will play out, such as how expenses are divided, how and when revenues are dispersed or reinvested, when one party doesn’t want to contribute further, what to do when one party wants out, and other situations typically accounted for when forming and operating an entity with multiple owners.

The benefit of forming a new entity is that (1) neither party can impede IP enforcement (except as provided in the operating document), (2) licensing and enforcement efforts are not hampered by the lack of all owners being involved, (3) each party “feels” good about co-owning the entity as compared to one-sided ownership arrangements. One downside for forming a new entity is the legal and other costs and time associated with forming and operating a legal entity.

Conclusion

The issues surrounding ownership, exploitation, and expenses related to jointly developed inventions should be address before the joint development effort beings. The default rule is that co-owners of a patent can exploit the patent without permission or accounting to the other co-owners, a situation that is often not desired.

“Unlike their elders, the young engineers couldn’t spot the key flaw in one of the complex systems they were working on, toss the problem around, break it down, pick it apart, tease out its critical elements, and rearrange them in innovative ways that led to a solution.”

“Unlike their elders, the young engineers couldn’t spot the key flaw in one of the complex systems they were working on, toss the problem around, break it down, pick it apart, tease out its critical elements, and rearrange them in innovative ways that led to a solution.” “If you can develop technology that’s simply too hard for competitors to duplicate, you don’t need to rely on other defenses. Start by picking a hard problem, and then at every decision point, take the harder choice.” – Paul Graham

“If you can develop technology that’s simply too hard for competitors to duplicate, you don’t need to rely on other defenses. Start by picking a hard problem, and then at every decision point, take the harder choice.” – Paul Graham