This post is designed to explain the difference between a U.S. Provisional Patent Application and a U.S. Non-Provisional Patent Application. In addition this document will explain circumstances in which one might be preferred over the other.

This post is designed to explain the difference between a U.S. Provisional Patent Application and a U.S. Non-Provisional Patent Application. In addition this document will explain circumstances in which one might be preferred over the other.

You may think of the provisional or non-provisional patent application as two routes to obtaining a patent. The non-provisional route providing a one step start to the patent process and the provisional route providing a two step start to the patent process. Either route, when properly carried out, can result in a patent. The two-step provisional process will take about one year longer to receive a patent than the one step non-provisional route.

Non-Provisional Route

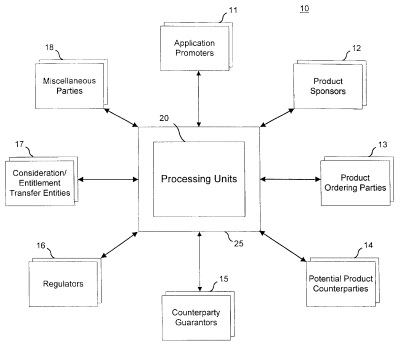

A U.S. non-provisional patent application is a patent application that when properly filed with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office is placed in a queue, examined by a Patent Examiner. If the claims of the non-provisional patent application are ultimately determined by the Examiner to meet the legal requirements, the non-provisional patent application may issue into a U.S. Patent. Each non-provisional patent application should contain a title, a background of the invention, a summary of the invention, a detailed description of the invention, one or more claims, and drawings. Also an oath or declaration complying with the applicable rules is also required. A fee of about 530 dollars is also required (assuming you qualify as a small entity).

Provisional + Non-Provisional within 1yr Route

You can think of the Provisional route as providing a two-step start to the patent process whereas the non-provisional application route is a one-step start.

The first step in the Provisional Route is to file a provisional patent application. The inventor’s oath or declaration and claims are not required for a provisional application. The provisional application filing fees are lower (about $125 for a small entity). The provisional patent application must include a description of your invention.

To ensure that resulting patent claims receive the benefit of the provisional patent application filing date, we recommend that a provisional patent application be drafted in the same manner as a non-provisional application, except that claims need not be included in the provisional application. In addition we often draft at least some claims for a provisional application. If an application fails to provide an adequate description of the invention, this may negatively impact the inventors ability to obtain a valid patent.

The Patent Office will not examine a provisional application and will not issue a patent directly from a provisional application. Therefore, there is no such thing as a “provisional patent†only a “provisional patent application.â€

So why would you proceed with a provisional application if it does not directly result in a patent? A patent can result from a non-provisional patent application filed within one year of the filing date of the provisional application, where the non-provisional claims the benefit of the provisional application. The filing of the non-provisional within one year is the second step of the two step process.

In order to retain the benefit of the filing of a provisional patent application, a non-provisional patent application that claims the benefit of the provisional application must be filed within one year of the filing date of the provisional application. If a non-provisional patent application claiming the benefit of the provisional application is not filed within one year of the filing date of the provisional application, then the benefit of the provisional application filing date will be lost.

The Provisional Route Takes Longer

The two-step provisional route takes longer than the 1 step non-provisional route. This is because the provisional application is never put in a queue at the patent office to be examined, only non-provisional applications are placed in the queue and examined.

Lets see how this works in the following example which compares the 1-step and the 2-step routes.

Non-Provisional – 1 Step Route

John’s attorney files a non-provisional patent application on January 1, 2012. The USPTO then places the application in the queue to be examined by a Patent Examiner. The average wait time until an Examiner examines a patent application is about 24 months. Therefore around January 1, 2014 an Examiner will being the examination process. Thereafter the Examiner will negotiate with John’s patent attorney, during what’s called patent prosecution. If the Examiner and John’s attorney come to an agreement on the scope of the claims in the patent application, the Examiner will allow the application to issue into a patent. The average wait time from the date of filing to the issuance of a patent is about 3 years. Therefore, if John’s case is average, he will be issued a patent around January 1, 2015 (3 years after the filing date). The resulting patent will have an effective filing date of January 1, 2012.

Provisional – 2 Step Route

Now lets look at a scenario where John first files a provisional patent application and then files a non-provisional application within one year. John’s attorney files a provisional patent application on January 1, 2012. The USPTO sends John’s attorney a filing receipt for the filing of the provisional but the USPTO does not place the provisional application in the queue to be examined by a Examiner. Remember provisional patent applications are not examined. John’s attorney places a reminder on his calendar to file a non-provisional patent application within one year of the filing of the provisional application. Before January 1, 2013, John’s attorney asks John if John wants to continue to pursue a patent on John’s invention. If John says Yes, John’s attorney prepares and files a non-provisional patent application claiming the benefit of the provisional application on or before January 1, 2013. Now the non-provisional application will be handled as described above in the one-step, non-provisional route, except the process starts one year later.

The USPTO now puts John’s non-provisional application in the queue to be examined by a Patent Examiner. In about two years, around January 1, 2015, an Examiner will being the examination process. Thereafter the Examiner will negotiate with John’s patent attorney during patent prosecution. If the Examiner and John’s attorney come to an agreement on the scope of the claims in the patent application, the Examiner will allow the application to issue into a patent. If John’s case is average, he will be issued a patent around January 1, 2016 (3 years after the filing date of the non-provisional application). The resulting patent will be giving the benefit of the filing date of the provisional application and therefore will have an effective filing date of January 1, 2012.

Therefore, as you can see each route results in a patent that has an effective filing date of January 1, 2012. However, the one step route results in a patent issuing a year earlier than the two step route.

Why Go the Provisional, 2 Step Route?

There are at least two reasons why one might choose the two-step provisional route.

Disclosure Needed Before Complete Development

Another reason the two step approach might be chosen is when disclosure is needed before the invention is completely developed. Often new products are developed on a deadline so that the product can be shown to a customer, presented at a trade show, or otherwise made available to the public. U.S. Patent law encourages the filing of a patent before certain events, such as a public showing or an offer for sale of invention. Therefore, if you are on a deadline to make an offer for sale or a public showing, but you believe that you will further develop the invention or you will add features to the invention within one year, a provisional application can be drafted and filed on the invention before any showing so as to provide the most protected approach.

Then if further developments are generated within the year of the first provisional application, additional provisional applications can be filed, and then the non-Provisional application filed within one year of the first provisional can claim the benefit of each of the provisional applications. Also, the new developments can be added to the non-provisional application filed on or before the one year date. The new developments will only be accorded a filing date when they are provided in a patent application. This approach reduces overall patent costs when products are developed over time when intervening offers of the invention or showing are required.

Cost Spreading/Shifting

The first reason is to reduce the up-front cost of filing a patent application and to spread the patent application cost over a year period. Lets take an example of a simple invention. A very simple invention might generally cost $3500 in attorney’s fees to prepare a non-provisional application. The filing fee for a non-provisional application for a small entity is about $530. Therefore the total cost of filing the application in a 1-step non-provisional route is $4030.

Now lets look that the two step provisional application route for the same invention. Lets assume that it cost $1500 in attorney fees to prepare claims for the invention. Since claims are not required in a provisional application the total attorney’s fees for preparing a provisional application on that invention would be $2000. The filing fee for a provisional application for a small entity is about $125. Therefore the total cost to file the provisional application on that same invention would be $2,125, which is $1905 less than the cost to file the non-provisional application. Therefore the up-front cost to file a provisional is less than the up-front cost to file a non-provisional.

However, a non-provisional application claiming the benefit of the provisional application must be filed within one year of the filing date of the provisional. Assuming there is no change in the invention and therefore no change in the application content at the time of preparing the non-provisional. Claims would be drafted and added to the content of the provisional application. The cost of drafting the claims would be $1500 (the cost not incurred above when writing the provisional application). The government filing fee for the non-provisional is $530. Therefore, the cost of the second step, filing the non-provisional application, is $2030.

Under the two step process, the cost of the application is split over a year’s time: $2,125 for the provisional application + $2030 for the non-provisional application, which totals $4,155. As you can see the two step process cost an additional $125—the cost of the provisional application— which is not incurred in the one step non-provisional process.

Therefore, in this example for a very simple invention, you can see that for the addition of $125 to the overall cost of the application, $1,905 can be reduced from the initial application cost and shifted about one year down the road.

Furthermore, if events develop during the time between the filing of a provisional application and the deadline for filing the non-provisional application, such that you do not want to proceed with patenting your invention, then $1905 is saved. This might happen if you determine the cost of commercializing your invention is more than expected or the market did not respond as expected to your invention. The two-step route gives you a year to determine whether a patent on your invention is worth further pursuing from a business perspective while keeping the initial application cost to a minimum. The foregoing cost represent a hypothetical example. Actual cost will vary depending on the invention and may not conform to the above example.