Ultramercial v. Hulu and Wildtangent, Dkt. No. 2010-1544 (Fed. Cir. Sept 15, 2011) [PDF].

Ultramercial v. Hulu and Wildtangent, Dkt. No. 2010-1544 (Fed. Cir. Sept 15, 2011) [PDF].

Update: WildTangent appealed to U.S. Supreme Court and The Court vacated the Federal Circuit’s decision discussed below and remanded the case the Federal Circuit to consider in light of Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., 566 U. S. ___ (2012).

Second Update: On remand from the Supreme Court, the Federal Circuit again found that the claimed method of monetizing copyrighted content on the Internet was a patent-eligible process.

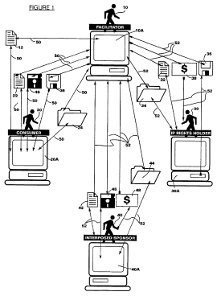

Ultramercial sued Hulu, YouTube, and Wildtangent Inc. alleging each infringed U.S. Patent 7,346,545. Hulu and YouTube were dismissed from the case. The trial court granted WildTangent’s motion to dismiss WildTangent from the case on the basis that the ‘545 patent did not claim patent-eligible subject matter. The Federal Circuit reversed finding the claimed method of monetizing copyrighted content on the Internet was a patent-eligible process.

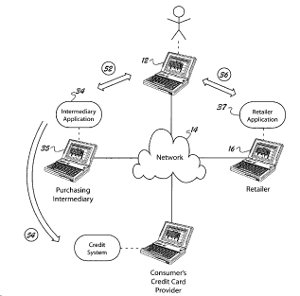

The ‘545 patent claims a method for distributing copyrighted products over the Internet where a consumer receives a copyrighted product for free after viewing an advertisement. The advertiser pays for the copyrighted content. Claim 1 of the ‘545 patent provides:

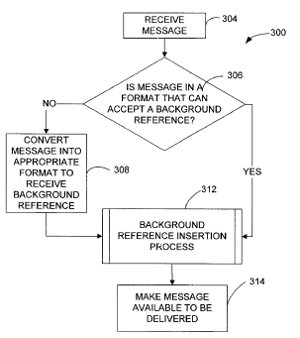

A method for distribution of products over the Internet via a facilitator, said method comprising the steps of:

a first step of receiving, from a content provider, media products that are covered by intellectual-property rights protection and are available for purchase, wherein each said media product being comprised of at least one of text data, music data, and video data;

a second step of selecting a sponsor message to be associated with the media product, said sponsor message being selected from a plurality of sponsor messages, said second step including accessing an activity log to verify that the total number of times which the sponsor message has been previously presented is less than the number of transaction cycles contracted by the sponsor of the sponsor message;

a third step of providing the media product for sale at an Internet website;

a fourth step of restricting general public access to said media product;

a fifth step of offering to a consumer access to the media product without charge to the consumer on the precondition that the consumer views the sponsor message;

a sixth step of receiving from the consumer a request to view the sponsor message, wherein the consumer submits said request in response to being offered access to the media product;

a seventh step of, in response to receiving the request from the consumer, facilitating the display of a sponsor message to the consumer;

an eighth step of, if the sponsor message is not an interactive message, allowing said consumer access to said media product after said step of facilitating the display of said sponsor message;

a ninth step of, if the sponsor message is an interactive message, presenting at least one query to the consumer and allowing said consumer access to said media product after receiving a response to said at least one query;

a tenth step of recording the transaction event to the activity log, said tenth step including updating the total number of times the sponsor message has been presented; and

an eleventh step of receiving payment from the sponsor of the sponsor message displayed.

Patent-Eligible Subject Matter. Section 101 of the Patent Act provides that any new process, machine, article of manufacture, and composition of matter is patent eligible subject matter. Three areas excluded from patent eligibility are laws of nature, physical phenomena, and abstract ideas. The Supreme Court has previously stated that a process under section 101 can include a business method. Further, while abstract principles are not patentable, an application of an abstract idea may be patentable.

Monetizing Content via Internet was a “Process” under the Statute. The Federal Circuit court found that the claimed method of monetizing and distributing copyrighted products over the Internet was a “process” under the patent statute and was therefore patent-eligible subject matter. The court turned its focus on whether the claimed subject matter was not patent eligible as being and abstract idea.

The Claimed Process was Not An Abstract Idea. The court stated, “[I]nventions with specific applications or improvements to technologies in the marketplace are not likely to be so abstract that they override the statutory language and framework of the Patent Act.” The court found that the ‘545 patent sought to fix the problem of declining click-through rates of banner advertising by introducing a method of distribution that caused consumers to view advertisements before granting access to the desired media such as video.

The court found that the claimed invention of the ‘545 patent was an application of an idea and not an abstract idea itself. The court termed the abstract idea as the idea that advertising can be used as a form of currency. Then the court noted that the patent disclosed a practical application of this idea. The court supported its conclusion by noting that the steps of the method are “likely to require intricate and complex computer programming” and that certain steps “require specific application to the Internet and a cyber-market environment” such as “providing said media products for sale on an Internet website.” It further noted that the invention would involve a “extensive computer interface.”

The court noted that the fact that the ‘545 patent did not specify a particular way (e.g. FTP, email, streaming) for delivering the media content to the consumer did not render the claimed subject matter impermissibly abstract. In addition, as the claim provided a controlled interaction via a website with a customer, the claim did not comprise only purely mental steps.

No Bright Line Rule. However, the court refused to specify a minimum level of programming complexity required so that a computer-implemented method is patent-eligible. Further, the court cautioned that not every use of an Internet website in a method will be sufficient alone to find that method patent-eligible.