Ultramercial v. Hulu and Wildtangent, Dkt No. 2010-1544 (Fed Cir. June 21, 2013) .

.

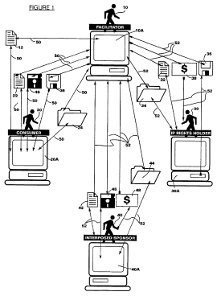

Ultramercial sued Hulu, YouTube, and Wildtangent Inc. alleging each infringed U.S. Patent 7,346,545. Hulu and YouTube were dismissed from the case. The trial court granted WildTangent’s motion to dismiss WildTangent from the case on the basis that the ’545 patent did not claim patent-eligible subject matter.

In the first round at the Federal Circuit, the court reversed finding the claimed method of monetizing copyrighted content on the Internet was a patent-eligible process. Then WildTangent appealed to U.S. Supreme Court and the Court vacated the Federal Circuit’s decision discussed below and remanded the case to the Federal Circuit to consider in light of Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., 566 U. S. ___ (2012). On remand from the Supreme Court, the Federal Circuit again found that the claimed method of monetizing copyrighted content on the Internet was a patent-eligible process.

The method steps of claim 1 of the ‘545 patent are recited in my original post on this case.

Chief Judge Rader, J. O’Malley and J. Lourie comprised the panel in this case. All agreed that the ‘545 patent recited patent eligible subject matter. But J. Lourie wrote a concurring opinion suggesting that the analysis in this case should track that provided in the plurality opinion that he joined in CLS Bank International v. Alice Corp., __ F.3d __, (Fed. Cir. May 10, 2013) (Lourie, Dyk, Prost, Reyna, & Wallach, JJ.,plurality opinion). It is quite surprising to suggest that the reasoning of a plurality opinion should be followed as binding precedent. C.J. Rader and J. O’Malley were supportive of a broad view of patent eligible subject matter in the CLS Bank case, whereas J. Lourie took a more narrow view–which is reflected in the opinions in this case.

Meaningful Limitations. The majority noted that assessing whether a claim was impermissably directed to an abstract idea involves a two step inquiry. The first is whether the claim involves an intangible abstract idea. And second, if so, then whether “meaningful limitations in the claim make it clear that the claim is not to the abstract idea itself, but to a non-routine and specific application of that idea.” When meaningful limitations narrow the scope of the claim so that the claims do not preempt all uses of the abstract concept, then the claim is less likely to be considered impermissably claiming an abstract idea. This is true because the application of an abstract idea can be patent eligible.

The majority noted that “with a claim tied to a computer in a specific way, such that the computer plays a meaningful role in

the performance of the claimed invention, it is as a matter of fact not likely to preempt virtually all uses of an underlying abstract idea, leaving the invention patent eligible.” It also noted that inventions with specific applications or improvements to technologies in the marketplace are not likely to be so abstract that they are not patent eligible. The court also noted that “unlike the Copyright Act which divides ideas from expression, the Patent Act covers and protects new and useful technical advance, including applied ideas.”

Wrenching the Meaning of Abstract. After reciting the 10 claims limitations from claim 8 of the ‘545 patent, the court concluded that “it wrenches meaning from the word [abstract] to label the claimed invention abstract.” The claim did not “cover the use of advertising as currency disassociated with any specific application of that activity.” The district court erred in stripping away the limitations and focusing on the asserted core of the invention. One of the claim steps included “providing said media product for sale on an Internet website” required a computer and the internet.

No Preemption of all Advertising. The court noted that the claims at issue here presented no risk of preempting all forms of advertising, let alone advertising on the internet. Further the claims were not directed to purely mental steps because, in part, the claims require a controlled interaction with a customer over the Internet website.

Overly Detailed Claims Not Required. The court noted that the claims did not specify any particular mechanism–such as FTP, email, streaming–for delivering media content to the customer. Yet the court found this did not render the claimed subject matter impermissibly abstract.

Comment. Judges from both sides of the CLS Bank case agreed that the claims in this case were not impermissibly abstract. This is the correct result. When a computer and the internet are integral components to the claimed process, the process does not preempt all uses of the underlying idea, and the process cannot be performed mentally or on paper, the claim is generally not abstract.

Here it appears that the subject matter–serving advertisements over the internet–is an inherently technology based invention. In other words, it is not something that could be carried out in one’s mind or on paper. In contrast, the claim steps in CLS Bank were capable of being performed on paper, if not directly as mental steps. Therefore, claims directed to processes that are carried out with a computer, but could also be performed in ones mind or on paper, will have a harder time overcoming the abstractness challenges with the five member plurality in CLS Bank.

This case shows that inherently technology based inventions still have a reasonable chance of being claimed in a way that will be found patent eligible with members of the Federal Circuit that are more hostile to software patents. Nonetheless the outcome of patent eligibility challenges related to software based patents are still quite uncertain and dependent on the panel of judges that are assigned to a given case at the Federal Circuit.