Centrillion Data Systems LLC v. Quest Communications International, 2010-1110 (Fed. Cir. Jan 20, 2010) [PDF]

Centrillion Data Systems LLC v. Quest Communications International, 2010-1110 (Fed. Cir. Jan 20, 2010) [PDF]

This case addresses the issue of whether infringement may be found for a “use”–under 35 U.S.C. 271(a)– of a system claim, which includes elements in the possession of more than one actor, e.g., the service provider possesses some elements and the end user possesses other elements.

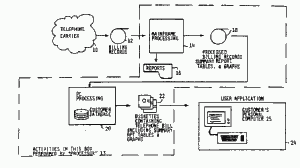

At issue in the case is Quest’s customer billing information systems. Centrilion asserts that Quest’s billing systems infringe U.S. Patent No. 5,287,270. Claim 1 of the ‘270 patent, at a high level, requires–as summarized by the court–a system for presenting information . . . to a user . . . comprising:Â (1)Â storage means for storing transaction records, (2) data processing means for generating summary reports as specified by a user from the transaction records, (3) transferring means for transferring the transaction records and summary reports to a user, and (4) personal computer data processing means adapted to perform additional processing on the transaction records. Centrillon acknowledged that the claim includes a a back-end system maintained by the service provider and a front end system maintained by an end user.

Quest’s billing system software has a back office system and a front-end client application that a user may install on a personal computer. When the user sign’s up for the billing software, the software made available to the users electronic billing information on a monthly basis.

Control means ability to put system into service. The court held that to “use” of a system for purposes of infringement “a party must put the invention into service, i.e., control the system as a whole and obtain benefit from it.” However “control” is not to be interpreted too narrowly. Control includes, as in the case of NTP, Inc. v. Research in Motion, Ltd., 418 F.3d 1282 (Fed. Cir. 2005), the ability to put the system as a whole into service. Therefore, a customer in NTP remotely “controlled” by simply transmitting a message (email)Â and it did not matter that the use did not have physical control over the relays of the system.

Customer’s Use. In Quest’s case, the court rejected Quest’s argument that its customers did not use the system because they did not control the back-end processing. Quest’s system has two operations, an on-demand operation and a normal operation. Under the on-demand operation, the user’s request directly generated a query returning data to the user. Under the normal, operation the system generated reports on a monthly basis that the user could retrieve. The court found that both the on-demand and standard operation of the billing information system was a “use” as a matter of law. The on-demand operation was a use because the customer controlled the system on a one request to one response basis. Under the normal operation, the court found that the user controlled the system by signing up initially with the service, which triggered the monthly reports to run. In both modes of operation, but for the customer’s actions, the entire system would never have been put into service.

Quest’s Use. The court determined as a matter of law that Quest did not “use” the patented invention. To “use” an invention, a party must “put the claimed invention into service, i.e., control the system and obtain benefit from it.” The court found that Quest never uses the entire claimed system because it never puts into service the :personal computer data processing means.” In other words, it does not use a front end system required by the claims. Further, “supplying software for the customer to use is not the same as using the system.”

Vicarious liability requires control or direction of actions of another. The court noted the only way to show that Quest used the patented system was if Quest is vicariously liable for the action of its customers so that the use by the cutmers may be attributed to Quest. The court stated that vicarious liability attaches when there is an agency relationship where one party controls or directs the action of another to perform one or more steps of a method claim. The court found Quest was not vicariously liable because Quest’s customer’s are not its agents and Quest did not direct its customers to perform.

“Making” requires combining all the elements of the claim. The court found that Quest did not “make” the invention–under section 271–because Quest manufactures only part of the claimed system and does not make the “personal computer data processing means.”